Drawing Turner Family Stories: An Interview with Marek Bennett

Drawing Turner Family Stories:

Interview with Marek Bennett

Turner Family Stories is a recent publication from the Vermont Folklife Center (VFC) that brings together cartoonists and oral history to share the family stories and personal experiences of Daisy Turner of Grafton, Vermont with new audiences. The Turner Family Stories project connected a group of New England cartoonists including Marek Bennett, Frances Bordeleau, Joel Christian Gill, Lillie Harris, Robyn Smith and Ezra Veitch with the Turner Family Collection in the Vermont Folklife Center Archive. It is a part of our larger effort to explore non-fiction cartooning as a way to share our archive and ethnographic research with the public.

To learn a little bit about how the cartoonists themselves reflect on their participation in the project, we reached out to talk with them about their work. This post is the fourth in a series exploring the artists’ sides of Turner Family Stories.

Marek Bennett is a New Hampshire-based cartoonist and runs Marek Bennett’s Comics Workshop. He has published several books in the genre of historical graphic novels, including The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby (Vol 1 & 2), based on the diaries and letters of New Hampshire schoolteacher Freeman Colby and his contemporaries (including Vermonter Wilbur Fisk). Marek has also taught non-fiction and ethnographic cartooning workshops for VFC and at the American Folklore Society annual conference. This interview was conducted by VFC Director of Education Sasha Antohin over Zoom, which allowed a discussion of Marek’s comic pages. The text has been shortened for clarity and brevity.

What were some of your initial impressions when hearing about the idea?

I'd been working on a lot of Civil War comics, and I'm very interested in how stories enter the historical record and who gets to tell the stories and how that creates a sense of identity in a community. And Andy [Associate Director and Archivist at the Vermont Folklife Center] mentioned, “You know Daisy Turner. You would know her from the Ken Burns Civil War documentary.” And I remembered her from that ...I just thought, “Oh, that's really interesting that this old woman and her poems can be a vessel of history, can be a bearer of history, a shaper of history, and there she is showing up alongside these academic historians.” And I got very interested in the project from there.

How was the process of selecting the specific story that you ended up illustrating?

I'm working so much on Civil War stuff and I happened to be drawing in 1863 at the time, and here's Alec Turner in 1863, linking up with the 1st New Jersey [cavalry]. And it just made sense for me to work on that story …And ultimately what I ended up focusing on was his description of the end of the war (or Daisy's telling of his description of the end of the war), which I found so interesting. It grabbed me because it was so apocalyptic … it's the beginning of his story, really. I realized that's the beginning of how he survives the horrors of war and goes in search of his Promised Land ...I realized it was kind of a transition, a transition from the end of the world to something better.

I know you're also an educator yourself. Were you thinking a lot of the reader and the audience, as you were writing this? Because in some ways you are filling in a certain picture of the way in which the Civil War is represented in New England.

If I'm drawing a comic for someone else to read, I have to in some way empathize with that other person, the reader. How are they going to receive this story? How are they going to look at it, and move through it? ... Can this comic go out into the world and communicate itself and make sense to people? And in some ways, I feel like there's another audience. It's in my head, or maybe not – I think, if this page were read by the person who wrote that primary source document, or if Daisy Turner herself looked at this page, what would she think, trying to empathize with the story as I've drawn it? What did she intend with her story? What made sense to her, why was she telling the story? … I think the ethnography angle is really important here. Jane Beck's work is saying, “Let me just tell you some anecdotes of a time I visited with Daisy, so you get a sense of how our relationship was, and what some of the issues were, and now let's step back and look at those issues. OK, NOW let's get into the story ...” We get a sense of the social context in which the story lives. It's like the habitat of the story, and how the story survives there.

How does nonfiction cartooning, if you agree with that term, allow us to engage with Daisy Turner's life?

My background before doing these Civil War stories was really autobiographical cartooning – drawing travel memoirs and diary comics and a lot of stuff based on, if not my own personal story, then the stories of people I meet and the places I encounter. And I'm very aware that, nonfiction versus fictional cartooning is a genre question. “What shelf do we put this on in the bookstore?” Because it's all fictional. It's all manufactured and processed in some way. And even if I create a purely fictional “fantasy” story, I'm going to be drawing from my own assumptions and experiences and my own cultural priorities. You can try this:Try to draw a diary comic of what happened to you today, and you will quickly realize, “Oh, I'm just fashioning a fictional narrative out of a few incomplete scraps of memory.”... But if the storyteller is no longer with us, or they're not drawing the comics themselves, then I have to put myself in their shoes and try to understand what our common connections are that could help us understand each other. And the result here is NOT the graphic novel BY Daisy Turner, you know? It's a graphic novel of modern cartoonists' interpretations of the historical material, and it's telling us as much about [the artists'] values and our learning process as it is about the material itself.

What would you want the reader to be left with when they read the story?

My section ends with the arrival at Grafton. In looking around at the primary source fragments, I just kept coming back to that little gossipy newspaper clipping that said, effectively, “Oh, the snow's awful deep this year. And, by the way, you'll never guess who just walked up Main Street ..." Alec's group was going to be logging and living in tents up in the snowy woods, you know. I want the reader to kind of arrive at that point and say, “Oh, the adventure is just beginning. And oh, this isn't going to be easy.” They're strangers in this land too (just as in Maine), and they have a whole new set of challenges here. It's optimistic, but also, I hope, mysterious, and I hope it makes the reader want to want to hear about that adventure next, in the following chapters, or in further readings, or even in volume two or something, you know? That's what I aim for, I think in most of my stories – that the reader leaves feeling like their imagination's running, they're curious. They have some questions and they want to know more.

A holocaust, end of the world, and the start of Alec’s story

I'm very aware that if I go to a historical society here [in New England] and I say, “what's the historical record for the Civil War?” there are powerful historical forces that shape that record, and cause it to be, honestly, mostly white men's letters and diaries telling us about the Civil War. And those authors were presenting those diaries and letters to their families back home. So they only tell certain sides of the story, and they shape the story the way they and their audience want it to be. And what I've been trying to do in working with those records is to figure out how are they shaping it and what's that negative space that's left behind, and whose voices can add more perspectives to that story? And looking specifically at the letter collections that I was working with, I was really interested in how the authors were shaping this narrative of the end of the Civil War.

There's all different ways to tell that story. But here's this guy, Alec Turner. I assume he was telling these stories to Daisy when she was a kid, I don't know at what age. He's telling her, “The end of the war... was like the end of the world. It was a holocaust.” (I don't know if that's his word or hers, but he gave her that sense at least.) I want to put that narrative alongside the account of a New Englander like Freeman Colby, whose letters say, “I'm fine, I'm not in danger. I'm eating well. I broke my finger in a fight with a big German soldier,” you know, all these little stories that come home to New Hampshire... in the letters collections. I just thought, wow, that's a contrast, I want to hear Alec's full story... Starting at the end of the world and going out into this new world that coincidentally, all those letter writers and diarists from New England were also coming back to. So there is this sense of convergence here; that all these people are thrown into uncertainty and something new at the end of the world, together...

The watch and the Quarry

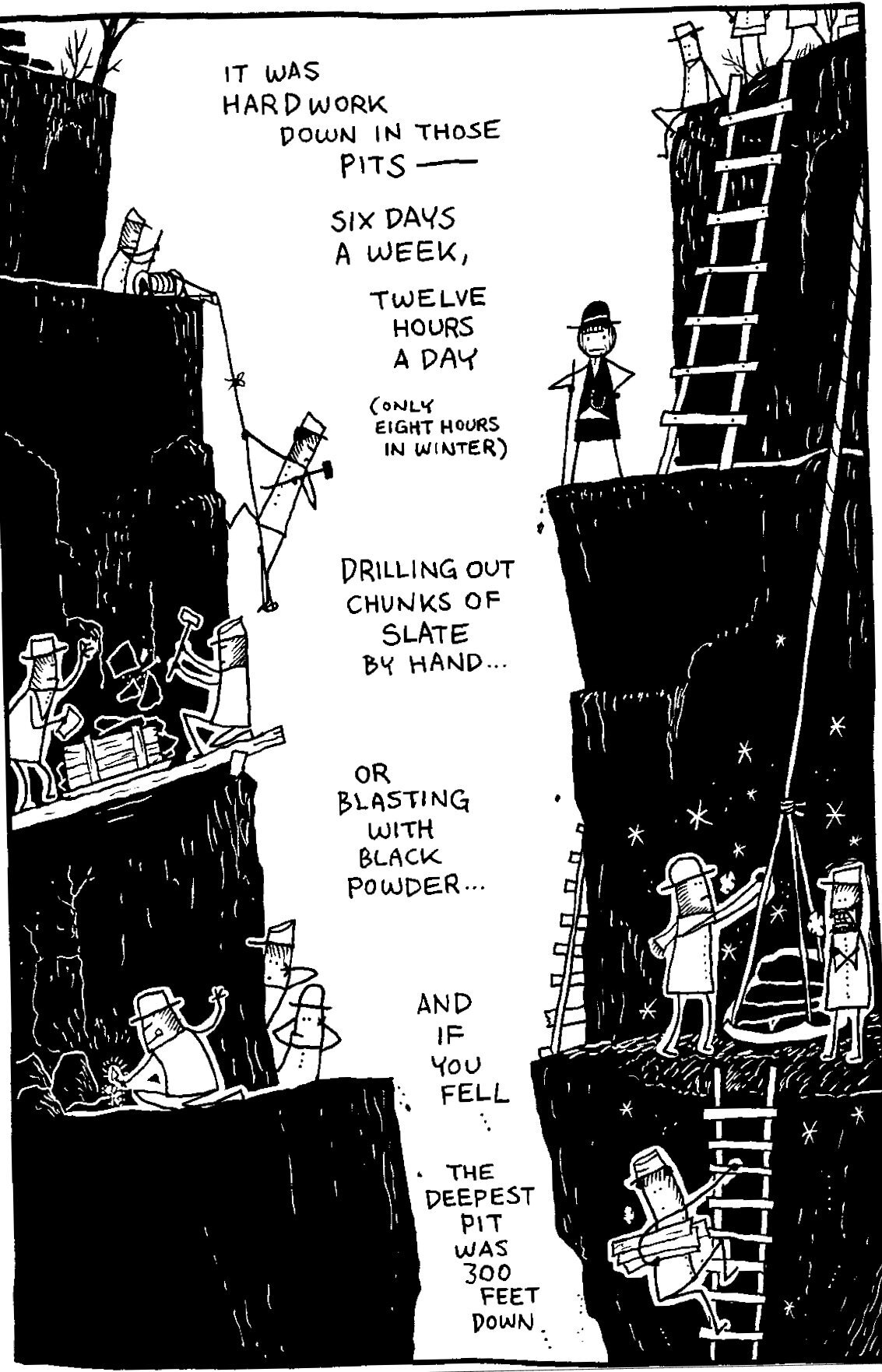

I decided I'd do this as a full page because I wanted to hint at that huge pit, but not show it in its entirety — just hint at it and make the reader feel like that page was going down and down... That's drawn from a photograph, that amazing photograph. And that's Alec. That's Alec Turner. And you can see in his body language, his whole story. He's dressed well. His body language tells you this is a guy who got this whole group together. They're willing to go with him because he's able to put himself forward as someone who has a plan and can say, “we're going to make this work.” Maybe this is just me projecting into his body language, but that's what I read in that picture. And then there are more stories embedded in the details. Even if we're not aware of it, you can scan that picture and you can see a working slate quarry. You can hold up a magnifying glass to each detail and you see how the guys are quarrying, because the picture is staged to show you all these different things. And you get up close to Alec Turner and there's a watch chain on his vest, right? And that's the watch! That's the watch the Colonel gave him. It's an incredible talisman that he carries, it is his connection with somebody else who helped him through this whole ordeal... And if you just glance at the picture, it's just a little detail. It's something you might ignore because, you know, that's not essential to the slate quarry story, but it's there...it's a symbol of another aspect of the story to me. So I just love that. If you know the stories, you look at the picture and you see something totally different — you pick up on different relations in the picture.

Daisy’s stories as “successful survivors”

I don't want to project too much into Daisy's intentions, but I kind of get a sense that she's a successful survivor. And her stories are successful survivors in that they got collected, I guess, for want of a better term, they got like archived in some way. They survived in what was, in many ways, a hostile environment to her voice and her stories. A white guy (like Freeman Colby) comes back from the Civil War and he has a couple of letters, you know, and of course the local New England village historical society wants those. Boom. They're in the archive. There's a lot of support. And furthermore, Freeman Colby was educated. He learned to write in a public school there in that village, you know, boom, he has all this support. And I don't get that sense of support from Alec's story and Daisy's story. And, maybe they didn't necessarily have an interest in sharing their stories with an archive, at least until almost the end of her life. But still, Daisy managed to keep those stories going, and then to get them into an archive. That whole context of Vermont Folklife Center's interest in her story, and then the archiving of it and attention to it from people who can protect it, preserve it -- I think that tells us a lot that Daisy was able to manage that.

Thank you Marek for speaking with us!

To learn more about the recordings of Daisy Turner that inspired Turner Family Stories, visit this page.

Marek Bennett is a cartoonist, musician and educator based in New Hampshire and leads discovery-based Comics Workshops for all ages throughout New England and the world beyond. To learn more about the art of creating historical graphic novels, see the Spring 2018 issue of Historical New Hampshire or visit https://marekbennett.com