Drawing Turner Family Stories: An Interview with Lillie Harris

Drawing Turner Family Stories:

Interview with Lillie Harris

Turner Family Stories, a forthcoming VFC book, brings together cartoonists and oral history to share the family stories and personal experiences of Daisy Turner of Grafton, Vermont, with new audiences.

The Turner Family Stories project connected a group of New England cartoonists including Marek Bennett, Francis Bordeleau, Joel Christian Gill, Lillie Harris, Robyn Smith and Ezra Veitch with the Turner Family Collection in the Vermont Folklife Center Archive. It is a part of our larger effort to explore non-fiction cartooning as a way to share our Archive collections and ethnographic research with the public.

To learn a little bit about how the cartoonists themselves reflect on their participation in the project, we spoke with them about their work. This post is the first in a series exploring the artists’ side of Turner Family Stories: A Graphic History.

Cartoonist Lillie Harris, originally from Prince George’s County, Maryland, is a student at the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, Vermont. Lillie reflected on their experience working with oral history transcripts as a basis for the story’s text, what it was like to create a comic with historical accuracy as a primary consideration, and capturing the essence of Daisy Turner’s character. This interview was conducted over Zoom, which allowed a discussion of Lillie’s comic pages. The text has been shortened for clarity and brevity.

What were some of your initial impressions when hearing about the idea?

Because I'm not a native to Vermont, I didn't know about Daisy Turner. So it was a lot of research that Andy [principal coordinator on Turner Family Stories and Associate Director and Archivist at the Vermont Folklife Center] helped me with. He sent me multiple books about Daisy’s life, picture books, also a prose book about her life that was really, really helpful. And initially it was a story that was supposed to be about her doll, a story of her as a child. But I'm very thankful that I brought it to Andy's attention the outdated language used in that story, of calling the doll a “Darkie doll,” just because Daisy was one hundred years old. I just didn't feel comfortable, like, using that same language in 2020 at the time.

And so Andy gave me free range to look through different stories from Daisy and pick which one I felt would be more comfortable for me to do. And so the one I picked is basically a ghost story that she told, which is great. Some of my comics deal more with like—they're all mostly fiction and they have attention to them, some would even call them horror comics. And so being able to do a nonfiction comic book can also make it really spooky. It was a lot of fun.

What drew you to this particular Daisy story?

Andy linked me to a site—I can't remember, but it's a radio archive of all the audio clips of Daisy describing some of her stories. The site had the doll story on there. It had the majority of the stories that are in the book on there, and there were about a dozen of them. And there was one that detailed her father's apparition come to her and then her going back home and saving her mother. And it just seemed like something out of an action movie. I was like “This is great!” For me, not coming from a strictly nonfiction background, it seemed the best way to go about it, of like, “This is still very fantastical, but also something that really happened.” So that drew me the most.

What would you want the reader to be left with when they read the story?

What I think is really interesting, is that from doing the research based on listening to all of her narrations, Daisy has a certain power in how she speaks and in acting on what she speaks about. So what I found so interesting about this story is that it's not necessarily her having the conviction based on something she said, but it's really the first time that I recognized her basing something off of her intuition. And so it's more of an insight as to, like, a gut feeling she has, like a spiritual influence she has, versus just staunchness, stubbornness-like resolve. So I would want to juxtapose this piece with other people's pieces, to be seen as more of a spiritual outlet.

What surprised you about this project?

What's funny is I think everything about it surprised me, because I was used to self-publishing my comics, but this is the first time that my comic would be with a series of other comics in a book...I guess, being able to see other people's comics, the other contributors. And you didn't really converse with them to know what they'd be doing or whose story would come first or second after that. But it all seemed to have a similar flow, which was surprising. So without us ever discussing, like, you know, “We want ours to be similar to Daisy or to reflect her father, Alec, in this way”—it's like we all had done our research and we're all able to make the same exact Daisy and Alec and family, which is really interesting.

How did this experience influence your work and process?

What's funny is I was never one to shun critique. I actually really love getting critique from my art. But it was interesting where you would send pages to Andy and he would tell you, not based on his own personal likes and dislikes, but how realistic something was in terms of the historical accuracy. And because I work in fiction, it's like, you know, “I'll just do whatever I want!” So it was a good lesson to have someone there who's more looking out for “would that train have looked like that in the thirties?” you know, which is something I just hadn't considered. So that's something I take away if I'm designing a character from a specific time, I think: “OK, they're not going to wear this. Remember, don't let your imagination get away with you!”

What about this experience, or even just your exploration of Daisy Turner's life, allows you to think about the stories, histories, representation of African-Americans in Vermont through your present day lens?

Before this I hadn't even considered that was a thing. So because I just moved here a year and a half ago, I didn't think much about the history of Vermont in general. I was just looking in a modern sense and said, “Well, it's me and three other black people here. So I guess that's how it's always been.” But now, after doing this project, I actually went to visit her hometown [Grafton]...I went to visit the historical site, I think her one- bedroom house with all these different photos all around it. And walking inside and looking at all the photos. I actually got really emotional. I was, like, seeing like a grandmother, like my grandma. It was just really, really beautiful. So I think I had subconsciously left that connection back in Maryland and hadn’t thought that these connections could still be here in a super predominantly white state. So, yeah, I guess just opening my mind up to the fact that we've always been here, whether or not our history has been documented in that way, it is the case. And the story definitely helped with that.

On the Vermont landscape and “fantastical realism”

This is a good one to talk about because I wanted to check with Andy throughout and make sure that I wasn't going too creepy. I wanted there to be a sense of foreboding in certain pages, but I didn't want to veer too far into “this seems super, super ominous.” And Andy actually really helped with that last panel, because initially it was kind of just a vague face and I remember a note he gave me back was, “Could you make it look more like Alec? Can you specifically make it look more like her father?” And because of the references he was able to give me—there are a lot of photos of Alec—I was able to match it a little bit more.

Now, this was a fun page because Andy, again, was giving a critique and was like, “We have to make sure that the landscape actually looks like where Daisy grew up.” And so at one point, there weren't enough trees and at another point it seemed like there were too many trees. So with his input it was really helpful because it was like you want to have some kind of fantastical realism, but still realism attached. So, again, he gave me some references to kind of, like, base where she would be walking in order to get to her house.

“Showing people speaking their natural dialect”

I mean, that's a thing that I really love, like, even outside of this project, is being able to show people speaking in their natural dialect or in different ways without it seeming like mocking in any way. Especially with Southern people. Living in southern Maryland, it's like usually seen as something that is unintelligent or demarks you somehow being like a jokey character when it’s just how people talk. So I really wanted to keep that same voice that she had.

Working with Daisy’s words and choosing an ending

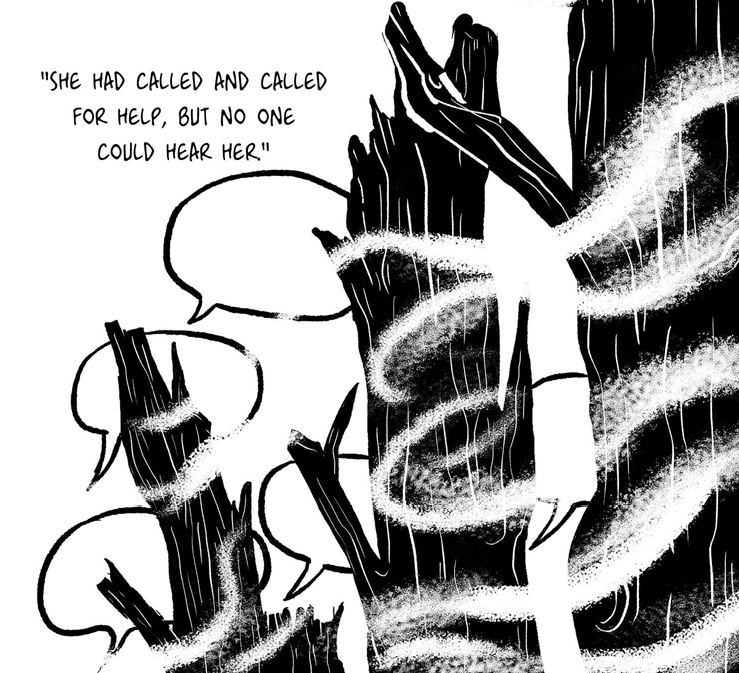

Typically with my personal work, I don't use a lot of narration and this is all narration—aside from I think in the beginning with their father calling her gal. And so with the speech bubbles being empty, with Daisy saying that no one could hear her, we're not able to even know what it is the mother was screaming or trying to say. So, yeah, there is a difference in this nonfiction work because you're basing it off of what Daisy said and having to stay true to that.

It wasn’t difficult, again, because of her audio. I feel like I had an assumption going into words like I'm going to have all of this really archaic, boring academic text that I was going to have to make, like, really theatrical. And she already had it be theatrical—the way she was telling it. I didn't switch any words around. Everything that I wrote was exactly how she was speaking. And so she ended it by saying “all the way from Vermont.” And so because it seemed like such a—there's another word, it's not exactly powerful, but just a very exuberant, kind of like, “ta da” way of ending it, I wanted the visual to be a bit softer. So I wanted it to carry a little bit of softness to it so that they balanced each other out a bit. And plus I wanted to draw ghost dad again! That was so fun.

The trauma with Daisy Turner’s doll story

Yeah, it's a shame, because my thoughts are that at the end of the story, I think we're left to think that this is such a prolific and self-assured child, which she was. And it's like, the means to get to that, I feel like are more harmful. So it's like I wish there was a way to have shown that Daisy was incredibly prolific and able to speak, in ways that we were not. It was just wild—all these words just came to her and she was just able to articulate them on stage as if they're being funneled to her as, like, a seven year old. And that's an amazing story.

It's just the crux of the story is, she did that based on the fact that she was given this like tar black doll that she loathed and talked about how much you loathed and all the trauma that comes along with that. It's one of those things that you have to pick your battles, so it's like maybe in small doses we can discuss the fact that she was able to express herself on stage without any kind of script, and it was amazing without having to go into what caused her to do that, why she felt compelled and so strong to do that...But also how much of that is not being honest about the history.

Thank you Lillie for speaking with us!

To learn more about the recordings of Daisy Turner that inspired Turner Family Stories, visit this page.

Lillie Harris is a cartoonist and illustrator currently living in White River Junction, and attends the Center for Cartoon Studies. For more on their work, visit http://www.lilliejharris.com