Did You Know? - Tony Barrand and the Atwood Family

The Vermont Folklife Archive is full of amazing first-person accounts of everyday life in Vermont and New England—past and present. In “Did You Know?” we share these stories with you.

This month, we continue our focus on material from the collection of traditional singer, musician, dancer and educator, Tony Barrand. Born and raised in England, Tony moved to the U.S. as a graduate student, and went on to become a professor at both Marlboro College and Boston University. Although best known as a performer and scholar of traditional music and dance from the UK, his interests encompassed traditional song from the US as well, including music from his adopted home state of Vermont.

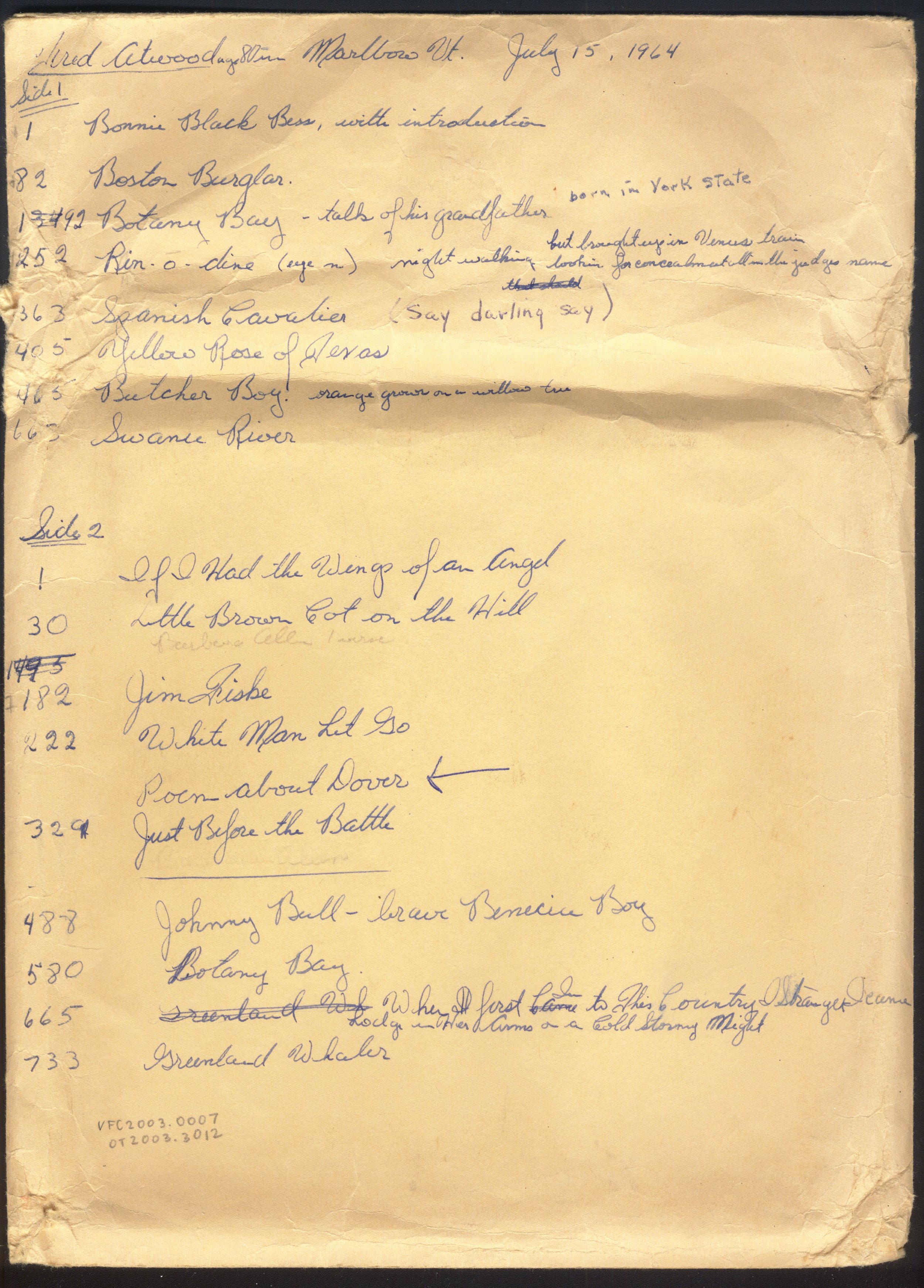

Envelope in which Margaret MacArthur stored her recordings with Fred Atwood.

In the early 2000s, with an eye toward a new recording project, Tony began to explore in depth the song repertoire of James and Mary Atwood of Dover, VT. Tony had been familiar with the Atwood material for decades. In 1919, Edith Sturgis, a wealthy summer resident of Dover, and musician, Robert Hughes, collected and published thirteen of the Atwood family songs in their book, Songs from the Hills of Vermont. In addition, Marlboro, VT musician and song collector, Margaret MacArthur—a long-time friend and colleague—had tracked down Fred Atwood, the son of James and Mary, and recorded him singing the family songs on two occasions in 1964 and 1967. Drawing on the Margaret MacArthur Collection in the Vermont Folklife Archive, Tony was able to access these recordings as well as other Atwood items that had been given to Margaret by Sturgis’s heirs. With Sturgis and Hughes’s book and the materials donated to Vermont Folklife by Margaret as a foundation, Tony then partnered with his neighbor and musician Keith Murphy to produce the 2010 album On the Banks of Cold Brook: Atwood Family Songs from the Hills of Vermont. Regarding the Atwoods, in the liner notes to the CD, Tony writes:

In 1870, Capt. John S. Barnes secured rights to land that became Dover, VT including half-a-mile of the "Fisherman's Paradise," Cold Brook. In 1899, his daughter Edith Barnes married S. Warren Sturgis, a teacher at the Groton (MA) School and Barnes gave them the property known as "Coldbrook." Stonemason James Atwood of West Dover was hired to rebuild the chimney. When he wasn't working, James would lean his chair against the wall and sing. Mrs. Sturgis wrote down all the words to the songs and ballads. The tunes she made the responsibility of Robert Wells Hughes, who had filled in as Music Master at Groton in 1916-1917. Over fifty songs were noted by Sturgis and Hughes from three singers: James Atwood, his wife Mary, and their close friend "Aunt Jenny" Knapp. Thirteen songs were given piano accompaniment settings by Robert Hughes and were selected for publication in 1919 as "Songs from the Hills of Vermont," #10 of the "American Folk Song Series."

(Tony Barrand, liner notes for the CD "On the Banks of the Coldbrook: Atwood Family Songs from the Hills of Vermont," © June 2010).

When Tony died in 2022, his family donated his papers to the Vermont Folklife Archive, where they form the Tony Barrand Collection. As part of establishing the collection, VT Folklife staff members Mary Wesley and Susan Creighton interviewed Keith Murphy. Below, we share excerpts of Keith discussing his collaboration with Tony on the Atwood Family project, along with some excerpts from the recording the two of them made of the Atwood songs.

Keith talks first about how they got started working together, and about Tony's approach to the project:

Keith: You know, as I say, we were neighbors. And so, we had started to see each other a little more often. So, I definitely started to feel more comfortable socially with Tony. And then, you know, one time I just kind of casually said, "Hey, Tony, you know, it'd be great if we could try singing sometime." And he said, 'Yeah!" And I think he almost instantly had this notion of, of what we could do, of like he had—It was clear that he'd had this project kind of somewhere in the back of his mind, this family of singers from West Dover, Vermont, the Atwood family. And I think he had learned some of their songs, you know, with John [Roberts] earlier, but he hadn't really delved into it. And pretty much from the start, that was his idea for the focus. And, John, this is something that John says, you know, Tony often worked around projects. You know, he liked approaching something like that rather than just sort of, you know, getting together and singing random songs. The idea of having a project to kind of delve into a theme of some kind, historical or otherwise, or the notion of a family repertoire. And so that was the open door.

You know, I was just describing how Tony liked a project, but that—it wasn't just a project of singing a group of songs, but it was everything. It's the whole history behind the songs. And, you know, very early on, after we started learning the songs, Tony started going down these rabbit holes kind of around the history of the collector of the songs, which is a whole sort of story unto itself and, you know, just the genealogy of the Atwood family and just, you know, on in all these different directions, which was amazing. But —and I was kind of there with him, for the first couple of, you know, metaphorical chapters of that. But he just kind of, he just kept going and going and, even I would be like, astonished at certain points to kind of see like--.

Susan: He was a scholar.

Keith: He was a scholar, yeah. Yeah.

Tony and Keith were both experienced performers by the time they started working together, and each brought that experience to the task of building a program of songs for the recording. Here, Keith talks about Tony's particular emphasis on weaving together the singing, the storytelling, and the connection to a sense of place.

Keith: I think the thing that Tony talked about was that—I mean, it was sort of like a ready-made program, like when, you know, as a singer, if you do a program if you put together a recording or a concert, you're looking for a range of songs you want kind of some kind of upbeat songs, maybe some slower songs, some sad songs, some funny songs. And the thing about this was that package was kind of already—it was a prepackaged thing. And you could, we could just sort of appreciate that range, you know, because there were some kind of silly, funny songs which Tony loved, you know, the Little Pig Song or, you know, just these little ditties and then some very old songs, Barbara Allen, you know, songs that had long history and then songs, other songs from that era. Tony loved the song—there's a song about Jim Fisk—that was a ballad of Jim Fisk—who was a whole character unto himself, but as it turns out, Jim Fisk is buried about three blocks from here. And there was—you know, he was a nationally known character. He was a colorful character with good aspects and maybe less good. And so there was a ballad written about him that I think was probably known, you know, around the country. And so that was like, it was kind of a topical song from the late 1800s. And, you know, Tony loved that whole thing, that whole range of songs.

Mary: Did you connect with, you know, that collection? We've heard other people say that, you know, Tony really was interested in and kind of moved by a sense of place, which I think that collection, having emanated from a particular family, and yeah, you know, so was that something that came alive for you?

Keith: Yeah, Tony and I—So just to kind of back up to the story of the Atwoods, so the Atwoods lived in West Dover and James was a mason and he befriended the Sturgis family because he'd been hired to work at their house. He was doing work at their house. And then he came to know Edith Sturgis, who ended up befriending James and but also publishing a whole collection of James' songs. But the Sturgis family had this property in West Dover that included this, what they called their playhouse. So, Tony—in typical fashion, right, Tony kind of figured out who the living Sturgises were and contacted them and where the property was. And we went to that property and got to go to the playhouse, which is like, it's like a you know, it was like a—it belonged to the family, but it was like a small theater, you know, a small, it was almost like a small grange hall almost, you know. And it had a stage and where I think the family would put on plays for, you know, for their extended family and friends. And there was a piano there. And I think Tony found some reference to James singing there. So, of course, Tony wanted us to sing when we went. We didn't do a performance there, but we got into that playhouse and, you know, the playhouse had not been maintained, you know, to a very high level. But the piano was there, maybe a little bit out of tune. But we sat down and sang and played through a bunch of those songs and that was, you know, that was kind of amazing. You know, that was not—it wasn't a hundred years, but it was getting on to 100 years probably after the time when that connection between James and Edith Sturgis would have happened.

Susan:Was there an audience?

Keith: No, just whoever was there with us from the Sturgis family. They were just sort of showing us around. So, it wasn't like a performance. Although I remember, you know, that notion we did talk about that, but it never came to pass. But then the same thing with Jim Fisk. You know, Tony used to love to go down to the graveyard [Prospect Hill Cemetery in Brattleboro, VT near Tony's and Keith's houses] to visit that pretty impressive, colorful monument down there for Jim Fisk. And Tony was very aware of that proximity. So, yeah, it, you know, it does very much tie in with Tony's enthusiasm and sense of the importance of connection with place.

Mary: And then to have you two working on that project as neighbors across the street is like a whole other layer.

-

Twas in the merry month of May when all the fields were blooming

A young man on his deathbed lay for the love of Barbara Allen

He sent his little 'pprentice boy to the place where she was dwelling

Saying master says you must come here if your name be Barbara Allen.So slowly she put on her clothes, so slowly she went to him

And all she said when she came there, young man, I think you're dying

For death is sprinkled on your face and sorrow in your dwelling

Much better off should I be then if her name be Barbara AllenDon't you remember the other day back at the drinking station

You drank a health to the maids all round and slighted Barbara Allen

He turned his face unto the wall, his back unto the maiden

Adieu, adieu to my friends all and woe to Barbara Allen.She had not gone 3 miles from town, she heard the church bell tolling

And every toll it seemed to roll, oh cruel Barbara Allen

And she looked east and she came west, she saw a funeral coming

Saying set you down, you corpse of clay, that I may look upon him

For cruel is my name, said she, and cruel is my nature.

I might have saved this young man's life by doing my endeavor.

The fairest young man in all New York died for John Allen's daughter;

The fairest young lady in this town will soon follow after.

Go dig my grave both long and deep, go dig it straight and narrow

This young man died for me today, I'll die for him tomorrow

The young man was buried, and she was buried beside him

And out of his grave grew a bright rose red, and out of her's grew a briar

They grew up to the mountain tall till they could grow no higher

They tied in a true lover's knot and withered away together -

If you listen awhile, I’ll sing you a song of this glorious land of the free

And the difference between the rich and the poor in a trial by jury you'll see.

If you've plenty of money, you can hold up your head and walk out from your own prison door

But they'll hang you up high if you've no friend at all; let the rich go but hang up the poor.I think of a man now dead in his grave, a good man as ever was born;

Jim Fisk he was called and his money he sent to the poor and the outcast forlorn

We all know we loved both women and wine, but his heart was quite right, I am sure.

He lived like a prince in his palace so fine, but he never went back on the poor.

If a man was in trouble, Fisk helped him along to drive the grim wolf from his door;

He strove to do right though he may have done wrong, but he never went back on the poor.Jim Fisk was a man wore his heart on his sleeve, no matter what people might say

He did all his deeds, both the good and the bad, by the broad open light of the day.

With his grand 6 in hand at the beach at Long Branch, he cut a big dash to be sure

But Chicago's great fire showed the world that Jim Fisk with his money remembered the poor.

When the telegram came that the homeless that night were starving to death slow but sure,

'Twas the "Lightning Express" manned by noble Jim Fisk to feed all the hungry and poor.Now what do you think of the trial of that Stokes who murdered this friend of the poor?

If such men get free, is there anyone safe to step from outside their own door?

Is there one law for the rich and one for the poor? It seems so at least so I say.

If you hang up the poor, why hadn't the rich ought to swing up the very same way?

Don't show any favor to friend or to foe, to beggar or prince at your door; (repeats)

The big millionaire they must hang up also but never go back on the poor. (repeats)

In addition to being a performer, Tony was also very much a teacher, and brought that aspect of himself into his singing as well. Here, Keith talks about Tony's approach, both at classes at the Brattleboro Music Center (BMC) and at the local Brattleboro pub sing he co-founded.

And Tony, you know, Tony loved teaching songs. Tony loved working with singers and was always incredibly supportive, you know, whatever it was, whether listening back to a student kind of singing their version of a song that we had done or coming in with a song that they'd found. When we used to--I think this was the very first class [at BMC], we did this thing that Tony had done as a prof at BU [Boston University] talking about folk songs. And he basically wanted to know what were the songs that people sang. And his concept was almost completely nonjudgmental. He wasn't asking, "What old songs do you sing? What Child Ballads do you sing?" He just wanted, he wanted to know, "well, what songs do you sing?" Because there was a part of Tony that kind of felt like if people know a certain song, if it's a song that's like in currency that other people can kind of sing along with, that, in a sense, is a kind of folk song. So, he had this very broad notion of what he sort of saw as, you know, the world of song.

You know, Tony, I never saw Tony look askance at a person's choice of song. He was--and he was delighted. He was delighted that the pub sing thrived, that it became this big thing. I think that was incredibly satisfying to him, to feel like he could do that. You know, in his work in general with John [Roberts] and with Nowell [Sing We Clear], they would often say they loved chorus songs. And again, it was another aspect of the thing that was like they weren't there--and Tony wasn't just there to be a performer. He didn't--you know, he enjoyed that. But he also loved being a song leader and he loved having a room, you know, make a lot of noise on a chorus. And so, with the pub sing, I think, you know, that really meant a lot to him to kind of have, see this kind of community and enthusiasm kind of grow for people just getting together and singing.

Tony passed away in January 2022, but his impact as a teacher, performer, singer, dancer, historian, and scholar on the many people who knew and interacted with him continues on in so many ways. You can explore more about Tony's life and work in the Tony Barrand collection at Vermont Folklife.