Family Traits: Art, Humor, and Everyday Life

“Family tradition is one of the great repositories of American culture. It contains clues to our national character and insights into our family structure.”

- Passage from Zeitlin, Kotkin, and Baker, A Celebration of American Family Folklore

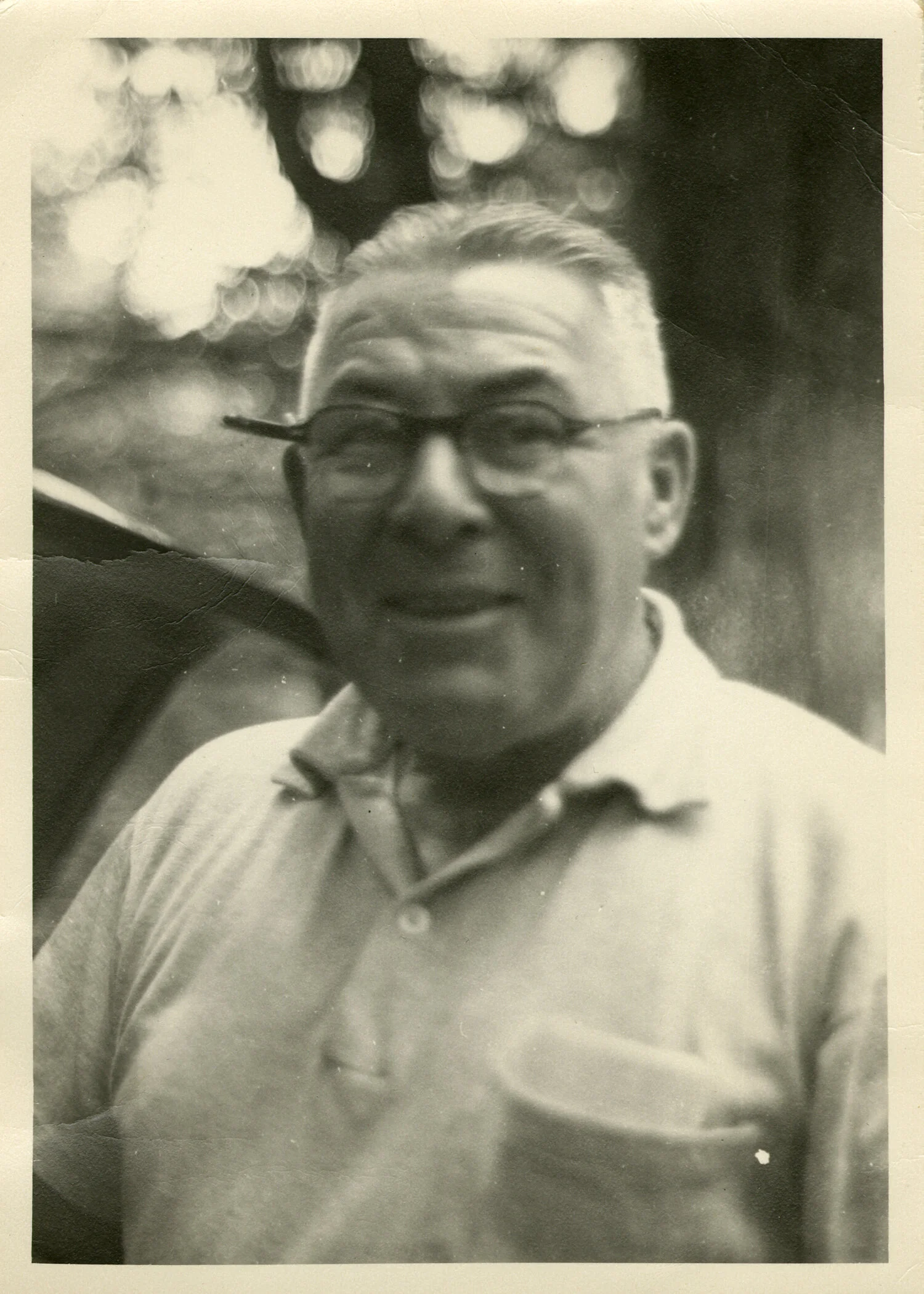

Stanley Lyndes was a “noticer.” He was also a maker.

As a child growing up in a multigenerational farm family, Stanley observed the quirks and foibles of the people with whom he interacted every day. He remembered each peculiar turn of phrase and was struck by the absurd qualities of everyday life that usually go unnoticed as “normal.” Like an anthropologist or a folklorist, he was able to reflect on his life at a distance, and he saw terrific humor everywhere.

Stanley channeled his noticing into the making of things, and over time these objects became touchstones for the generations of his family that have followed him, revered as both treasured artifact and the creative expression of a common past.

Many of his most ambitious works are on display here, and yet his grandchildren can easily reference by memory a seemingly endless stream of bows and arrows, finely-crafted boxes, miniature furniture, beautifully illustrated cards, and much, much more. At the root of all of this was “Gramps Honeycake,” loving, fun, and full of surprises, who bound his family together by creating a cast of characters that were their common property. Forty-two years after his death the things he made still resonate for his grandchildren and great grandchildren.

We all celebrate these kinds of family connections when we bake the birthday cake that our mothers made for us as children or tell stories about those special ornaments on the holiday tree. This is how family folklore is made—the only difference is that Stanley Lyndes did it in spades.

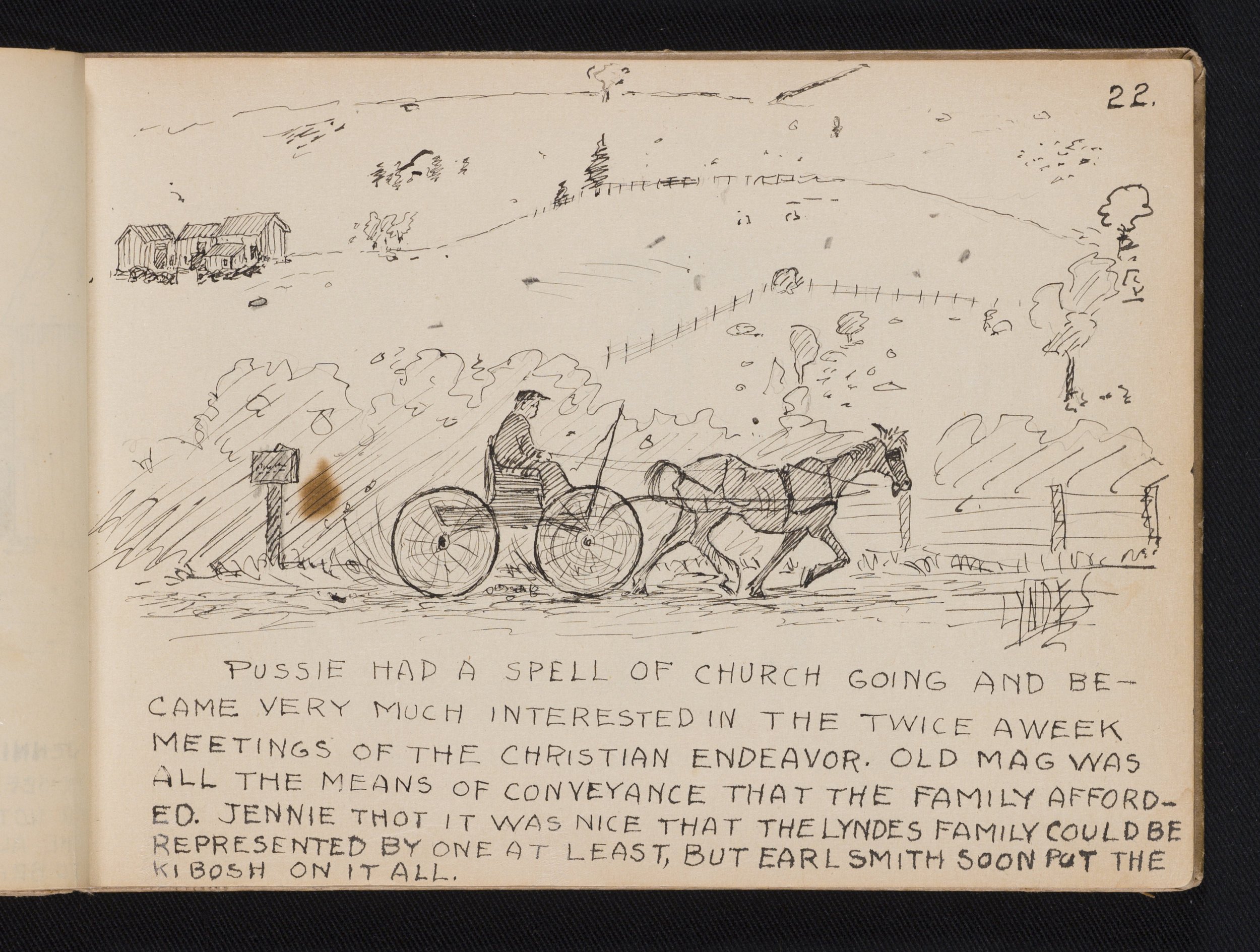

Biography

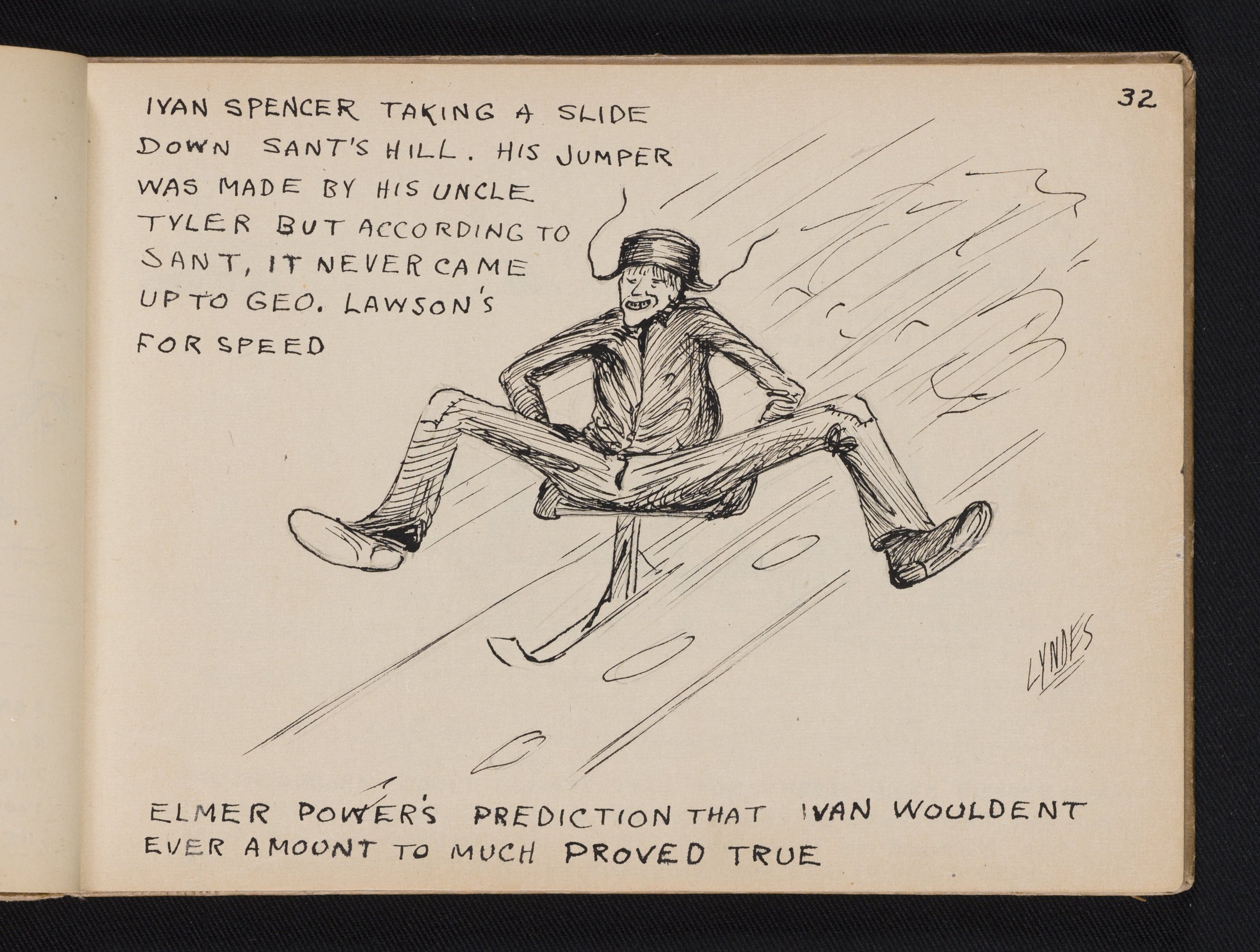

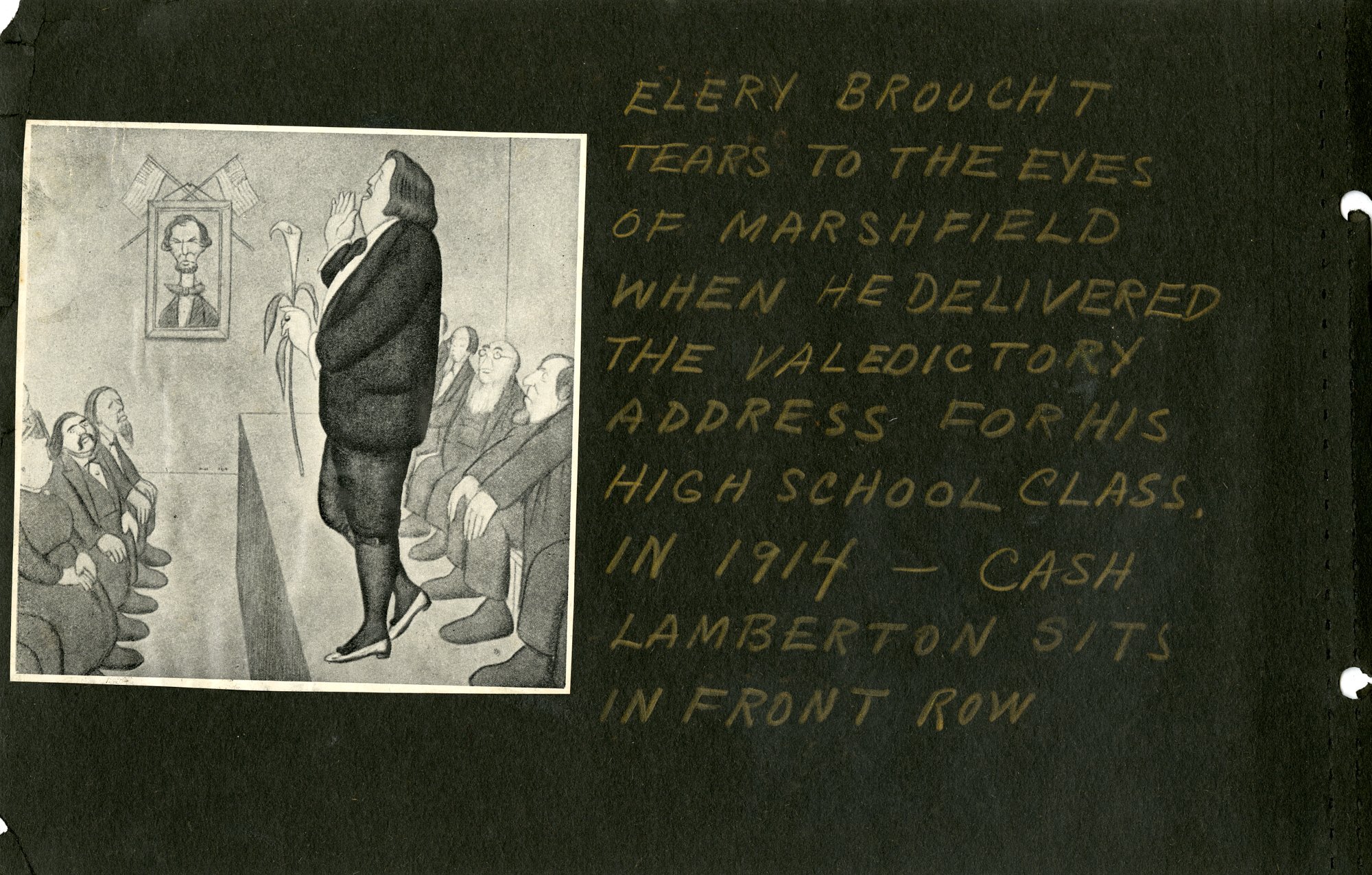

Stanley Lyndes was a teacher, craftsman, storyteller, artist, hunter and extraordinary grandfather. He was warm, good-humored, constantly creative, and sometimes impatient and stubborn. He loved making things and children, especially making things for and with his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Born in Calais, Stanley grew up on family farms in Cabot and Marshfield. From an early age he loved to draw and make things to entertain himself and his brothers. He attended local, one-room schools and graduated from Marshfield High School in 1916 and Montpelier Seminary 1918.

Pratt Institute

As a young man, Stanley attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York to study art and design to prepare to become a teacher.

While at Pratt he worked multiple jobs to support himself but found time for parties and theatrical spoofs with his friends. Summers, he worked haying in Vermont, which aggravated his asthma, or at a big hotel in the White Mountains. He hated the city so much that in 1922 he left as soon as he secured a teaching job without completing the final term.

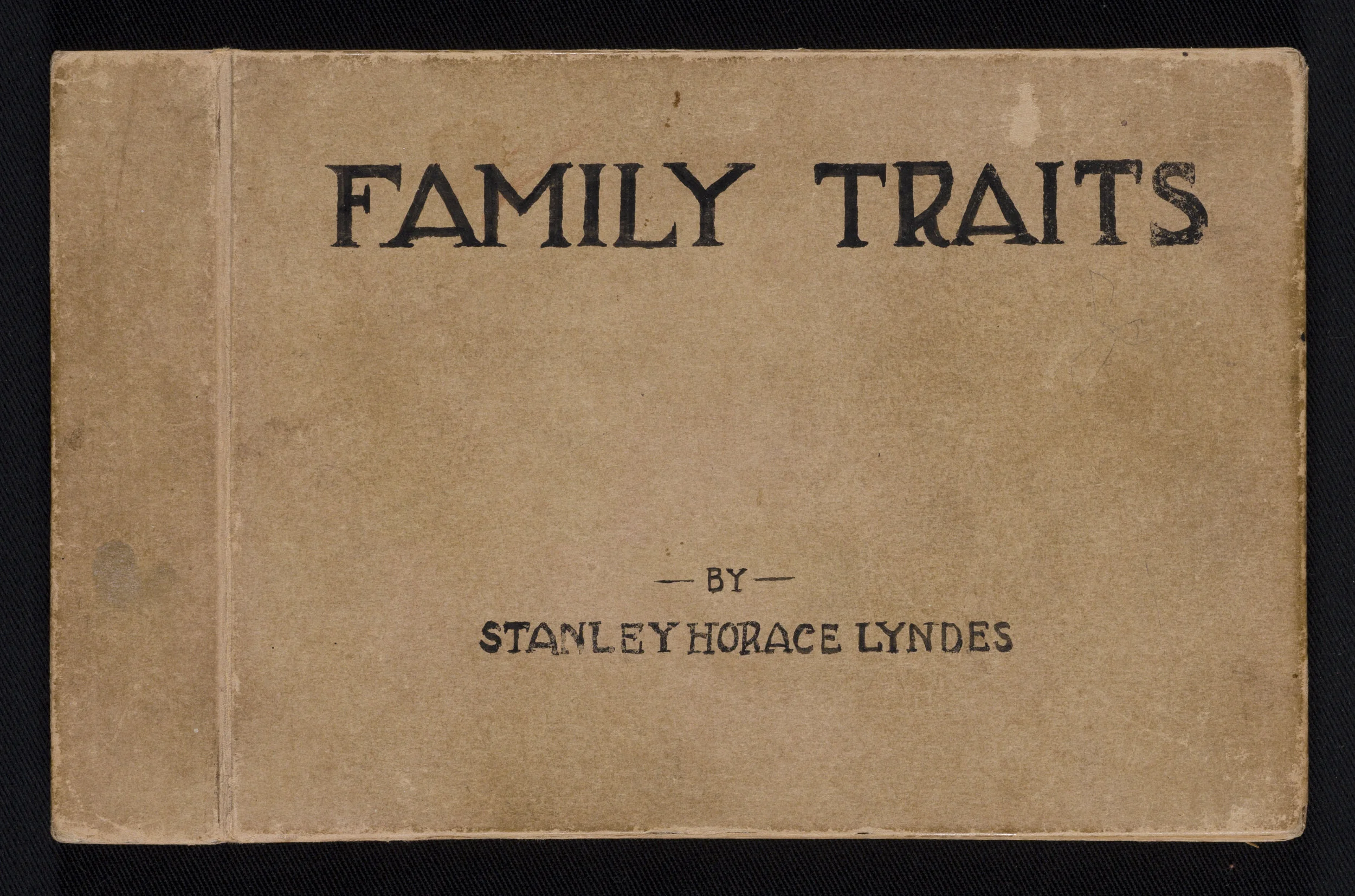

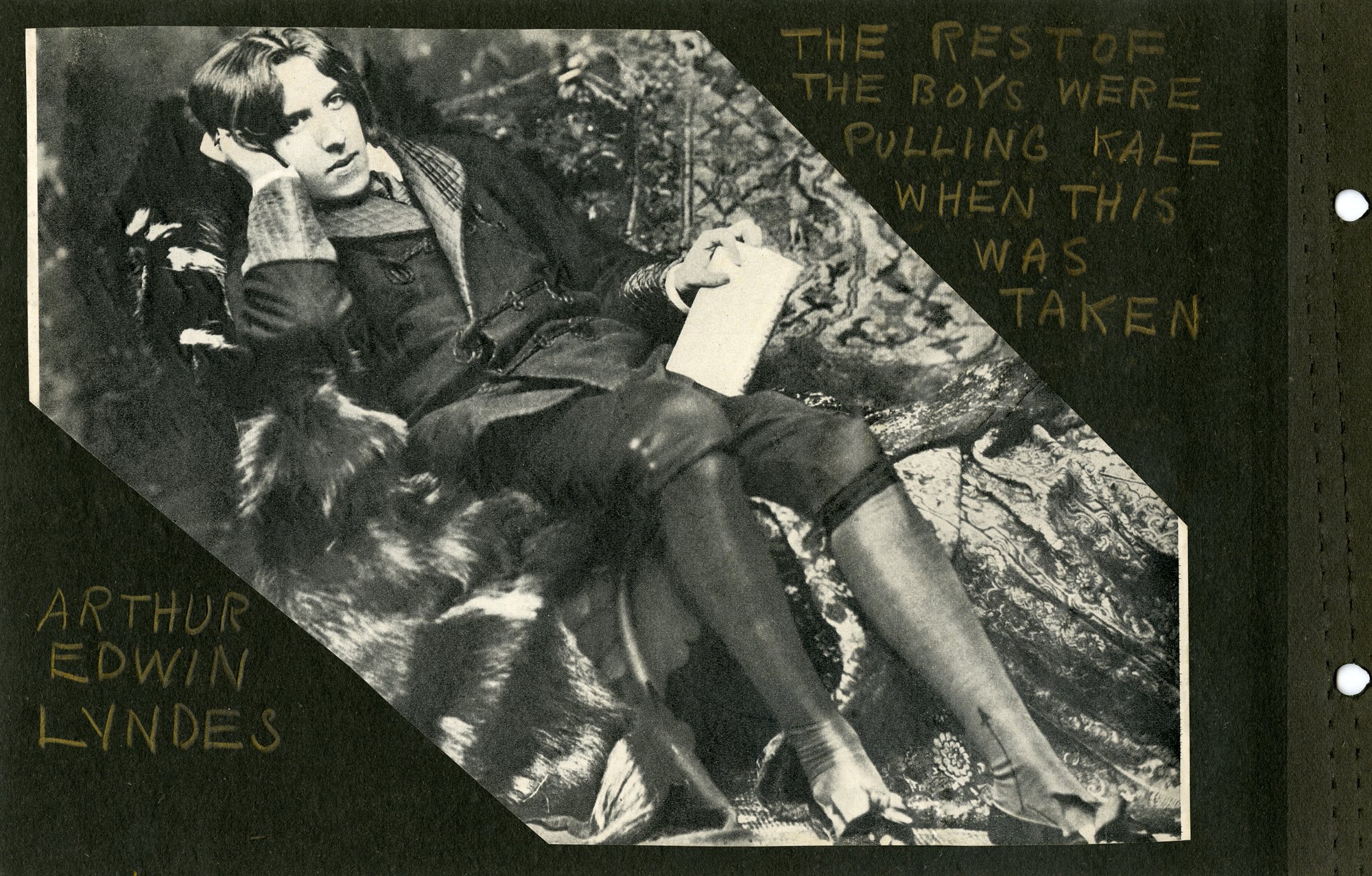

While at Pratt he took a bookbinding class and made a small blank book. His friends, who liked his stories of life back on the farm, encouraged him to use it for sketches of life at home. He titled it “Family Traits.”

Family and Teaching

Stanley married Evelyn Martin of Plainfield, Vermont and started teaching in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts, a neighborhood of Springfield.

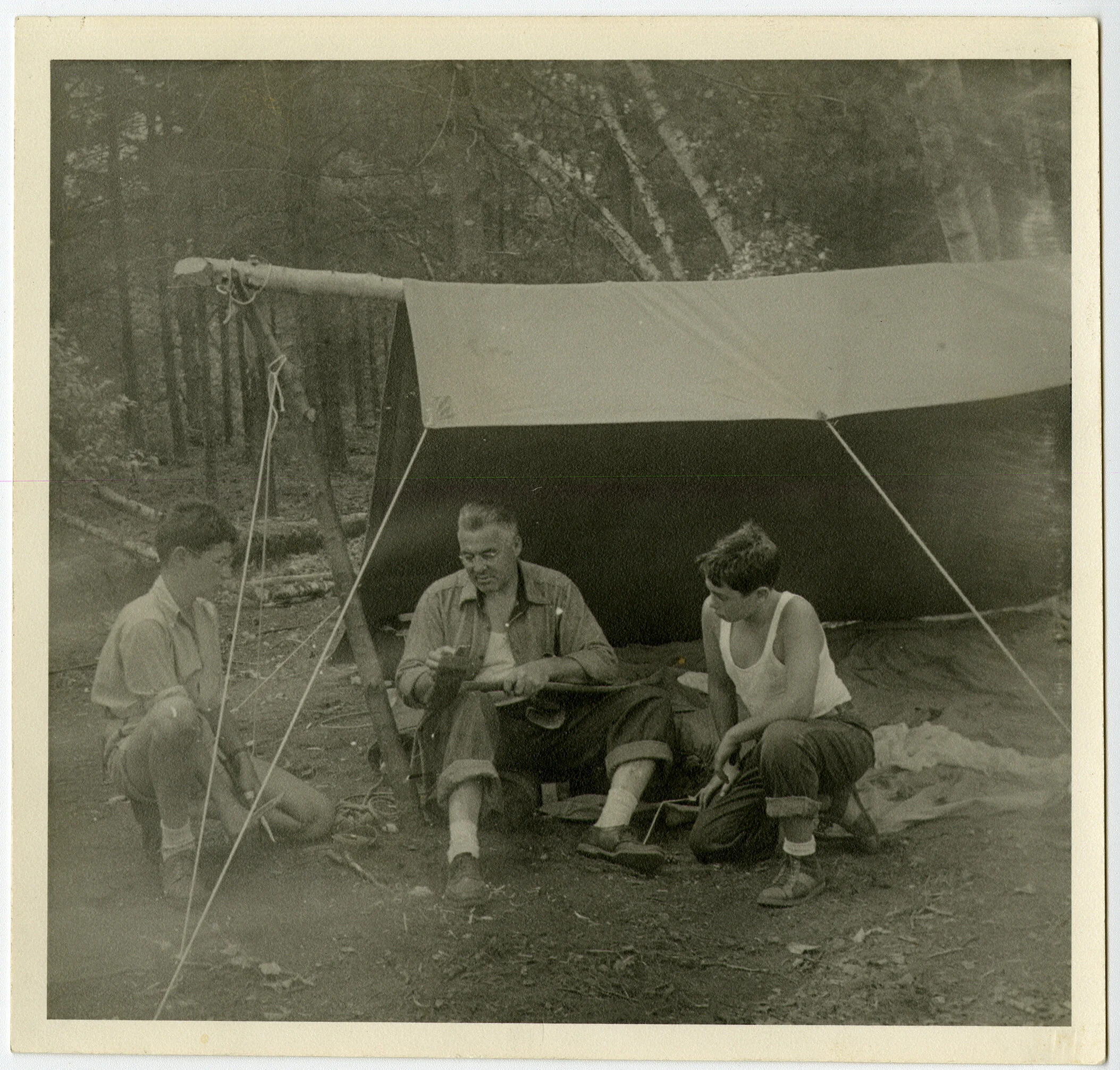

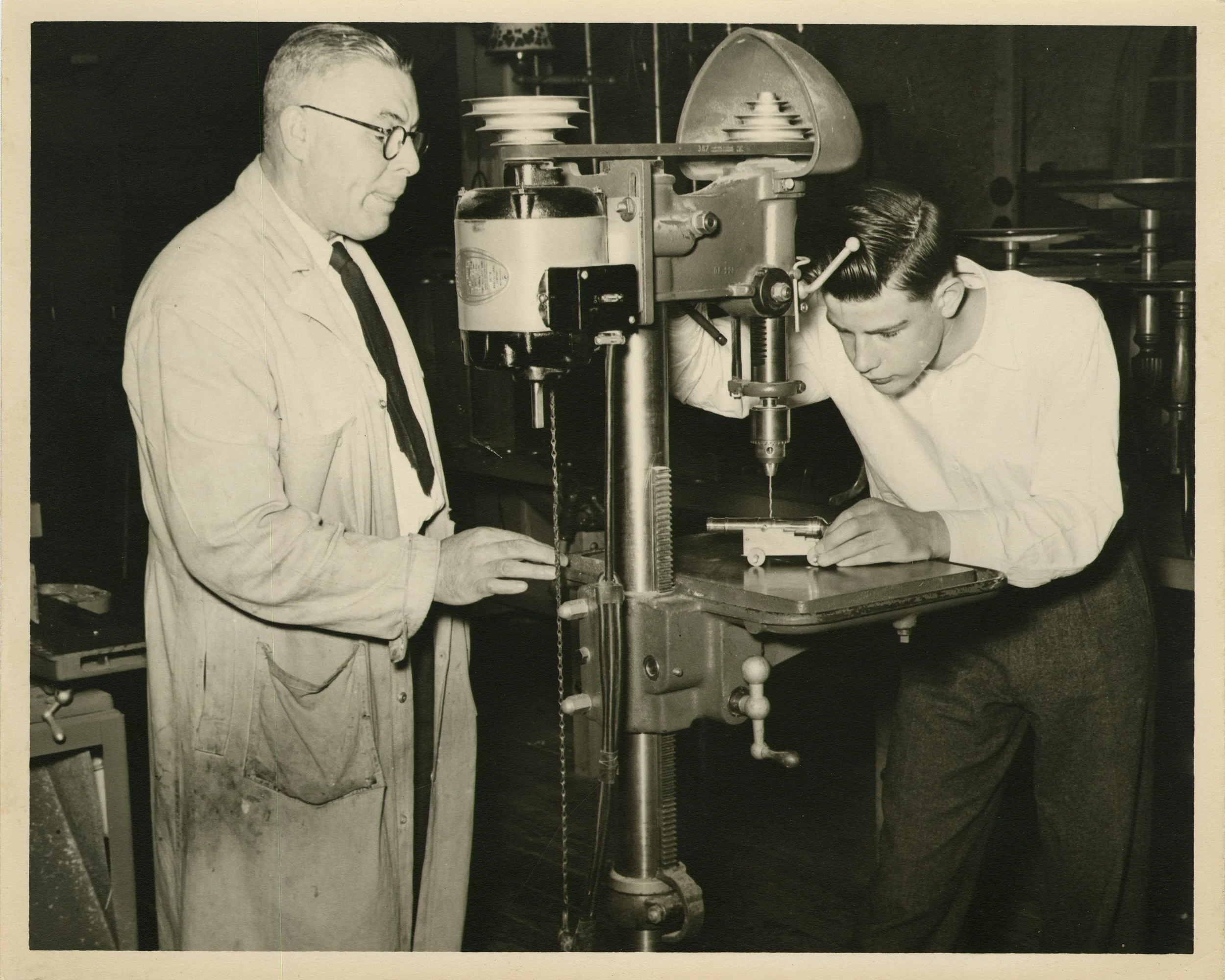

He taught “manual arts” such as drawing, mechanical drawing, and woodworking. Stanley and Evelyn raised their two children, Milton “Skeeter” and Jean in Indian Orchard. He worked summers at various camps for boys in Maine where he specialized in teaching archery, many handcrafts, and woods lore.

In the late 1940s, he began teaching woodworking and related arts at Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut.

The Honeycakes

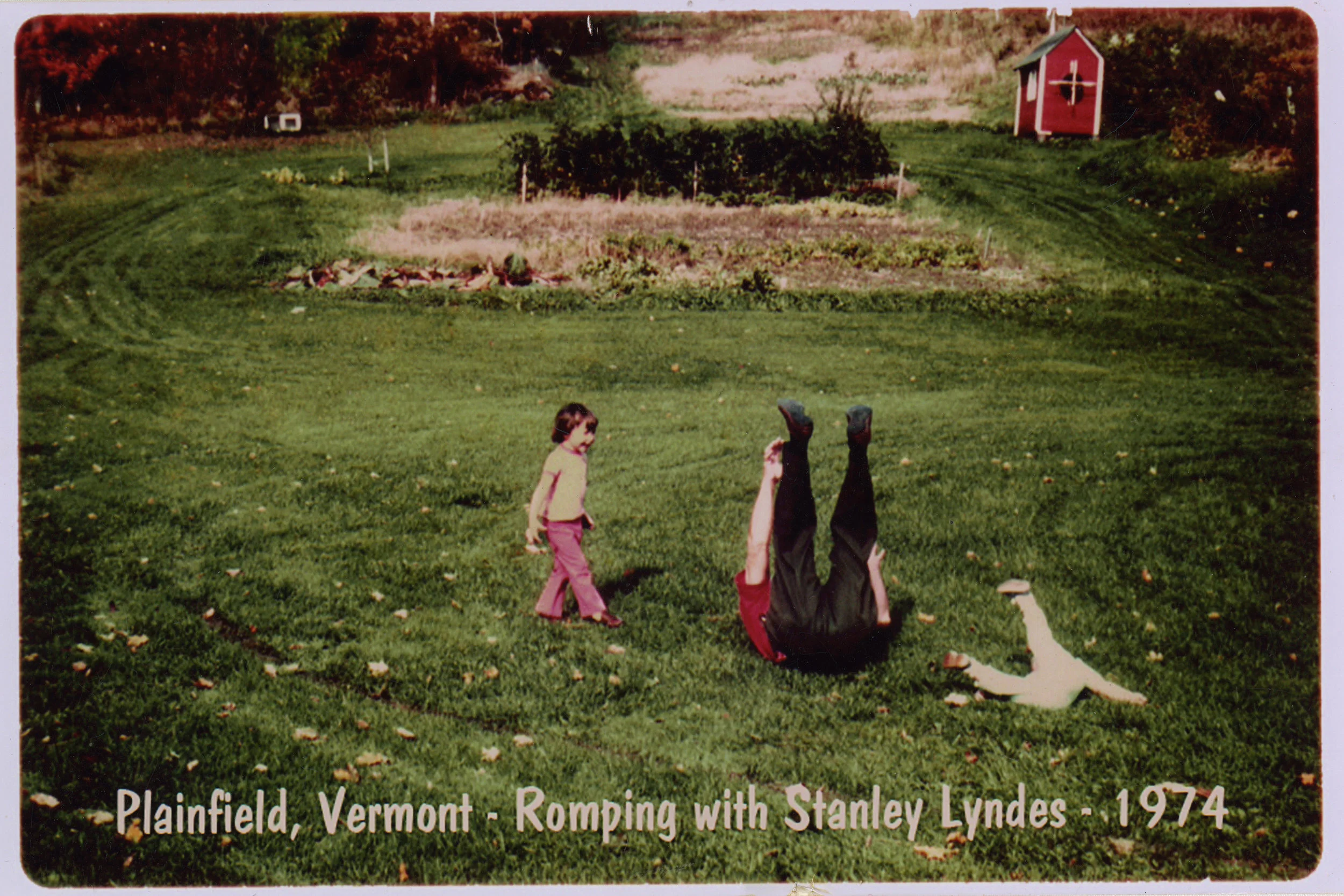

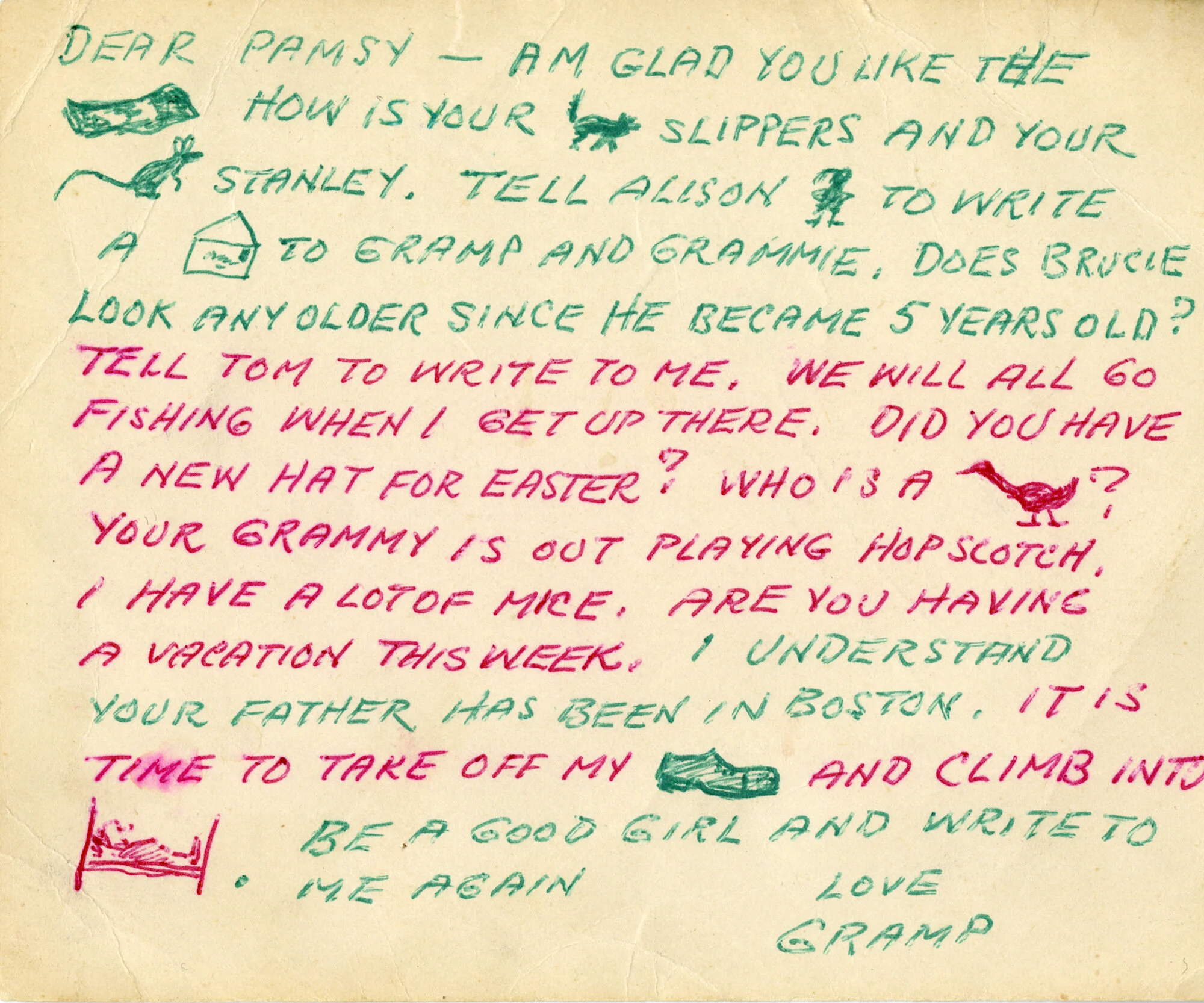

When the grandchildren started arriving, Evelyn had many pet names for them such as “lambykins” and “honeycake.” Leslie, the eldest, soon began calling them “Gramp and Grammy Honeycake.” The name spread throughout the extended family and to friends. When they retired to Plainfield, townspeople often referred to them as “The Honeycakes.”

Gramp made the grandchildren toys, sketched birthday cards, cooked for them and told them stories of animals and his childhood. He taught them about wood working, drawing, painting, fishing, hunting, growing things and watching wildlife. Grammy made nightgowns, doll clothes, and home-made bread. She was quiet, gentle and a better cook than Gramp, but if he decided to cook, she stepped into the background.

Before Stanley died in 1975, he had several years delighting two great granddaughters. Evelyn had developed dementia in the early 70s and died in 1985.

Family Traits

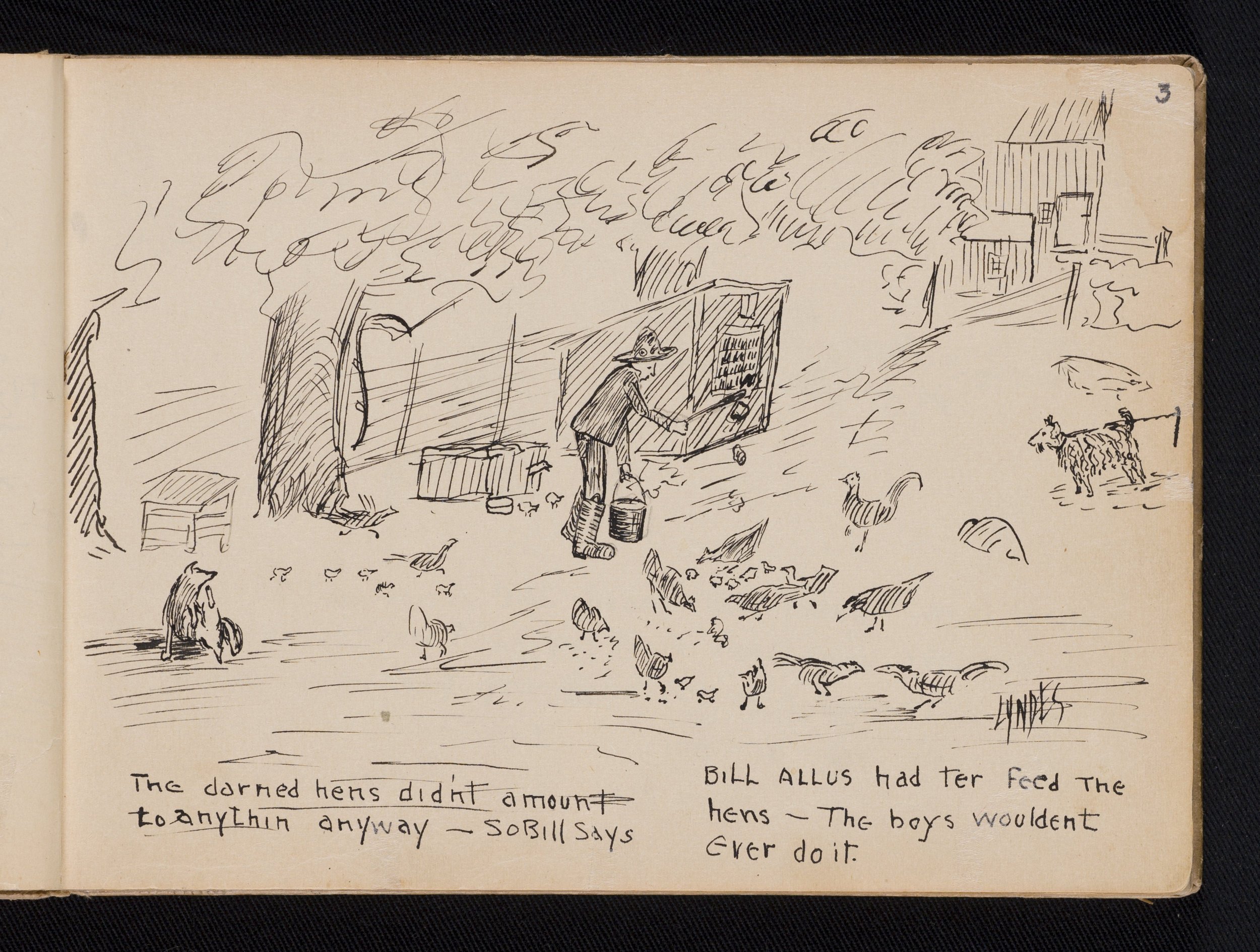

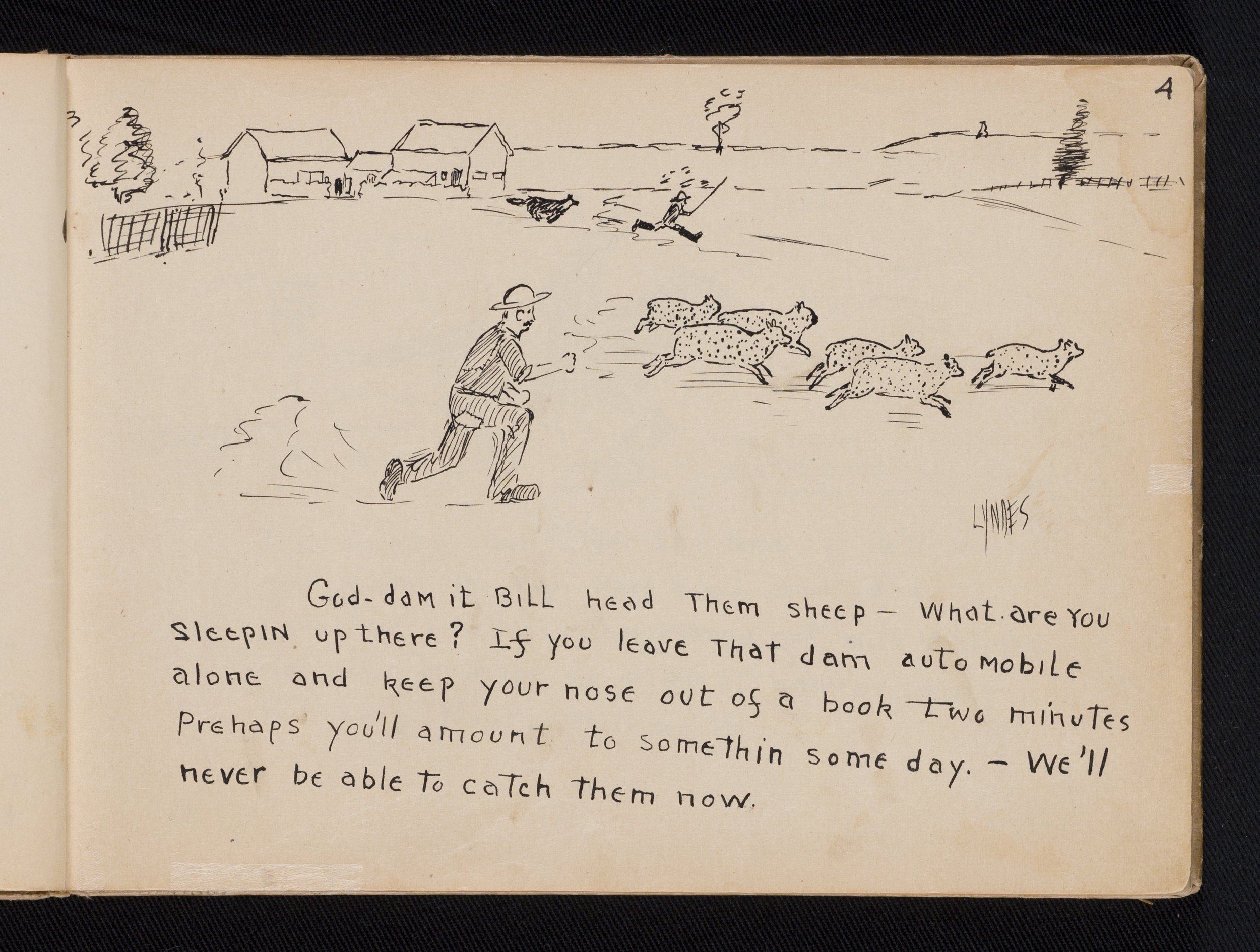

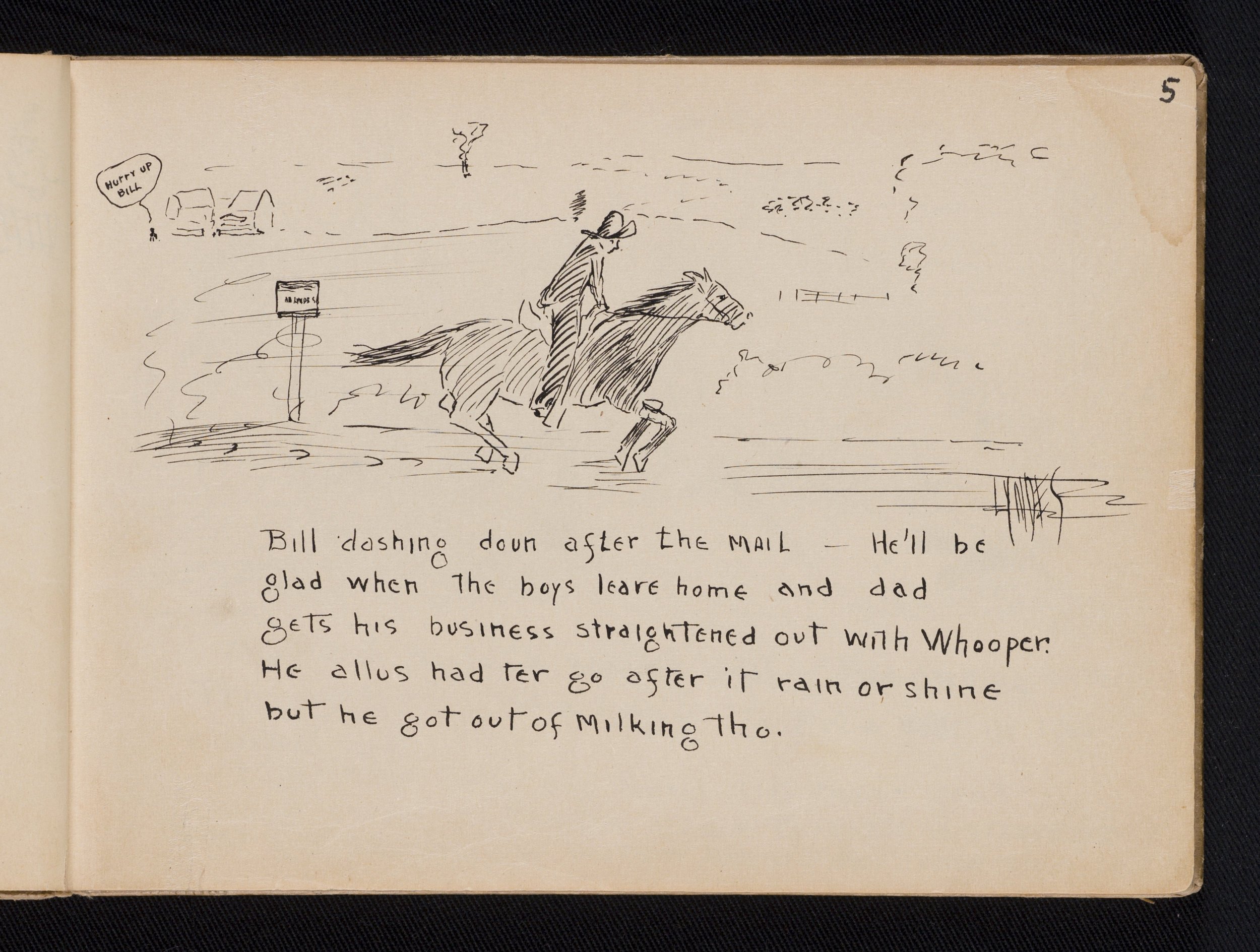

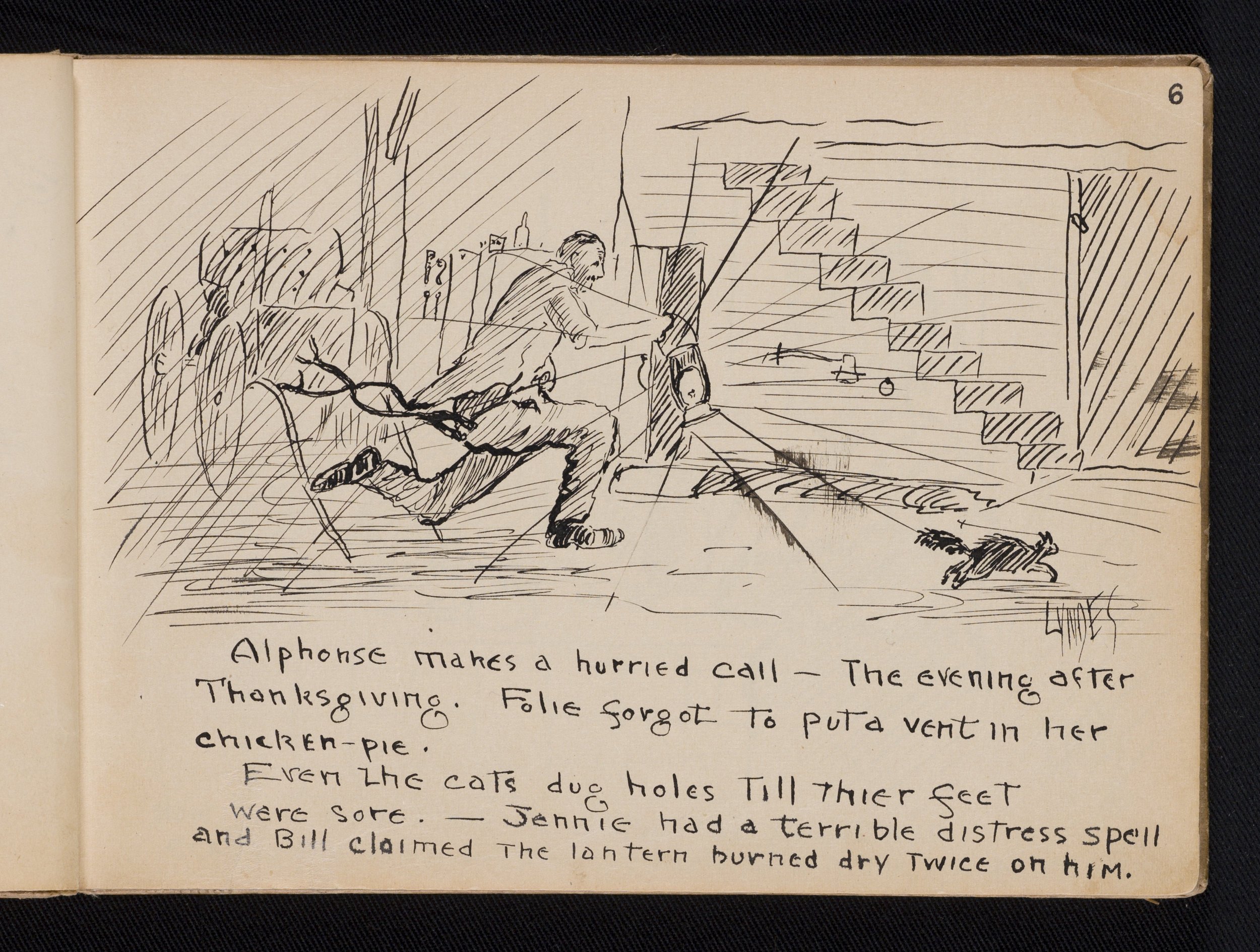

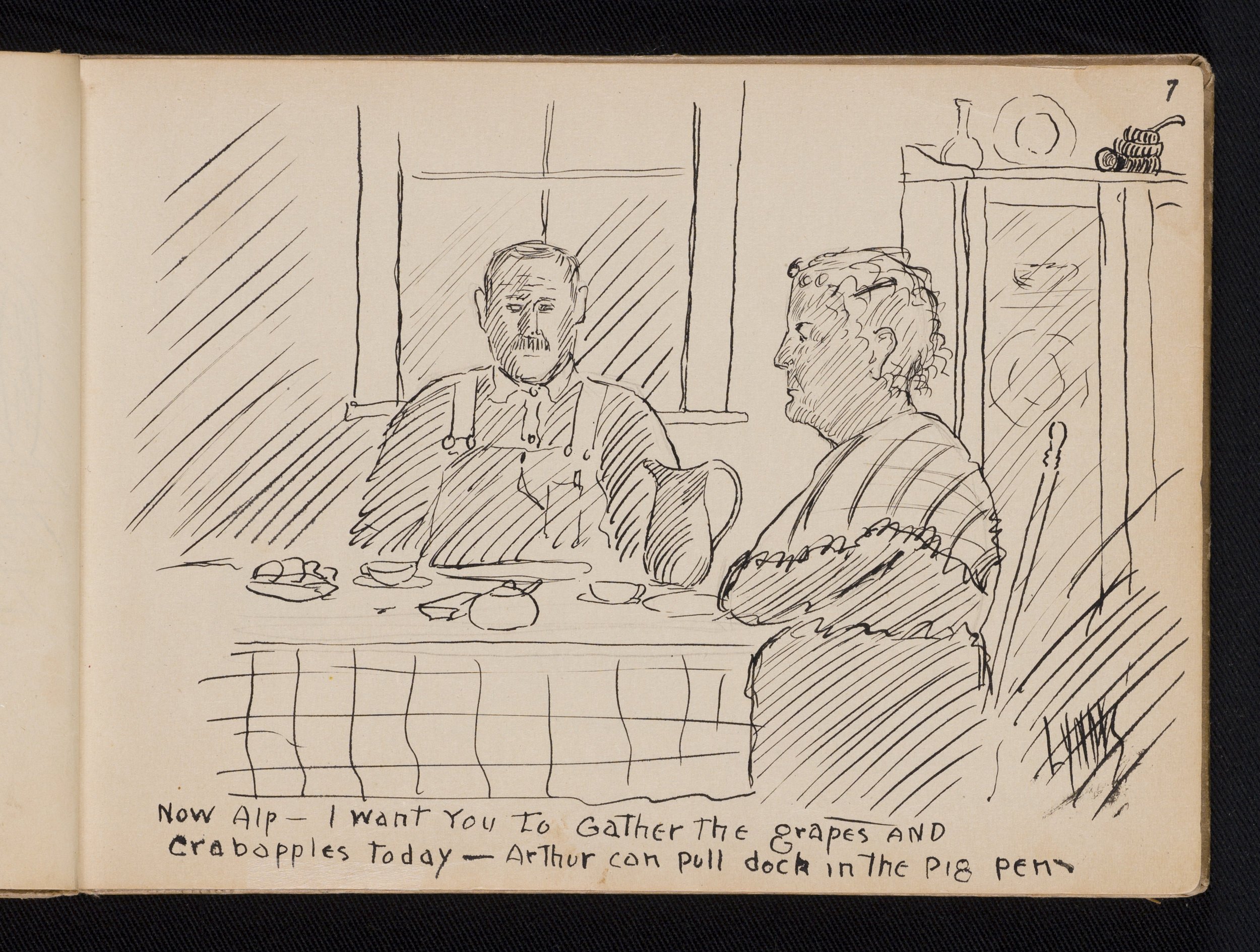

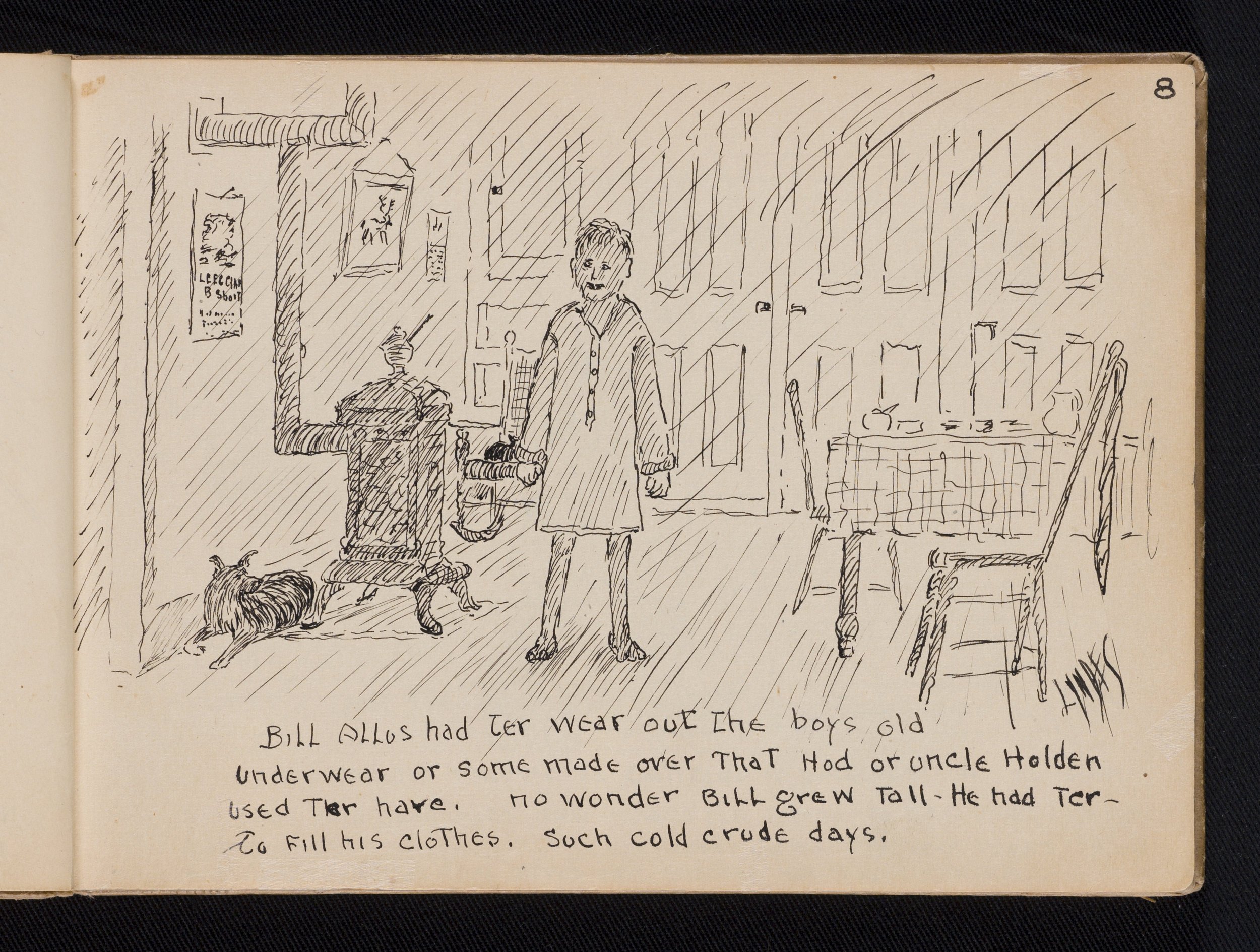

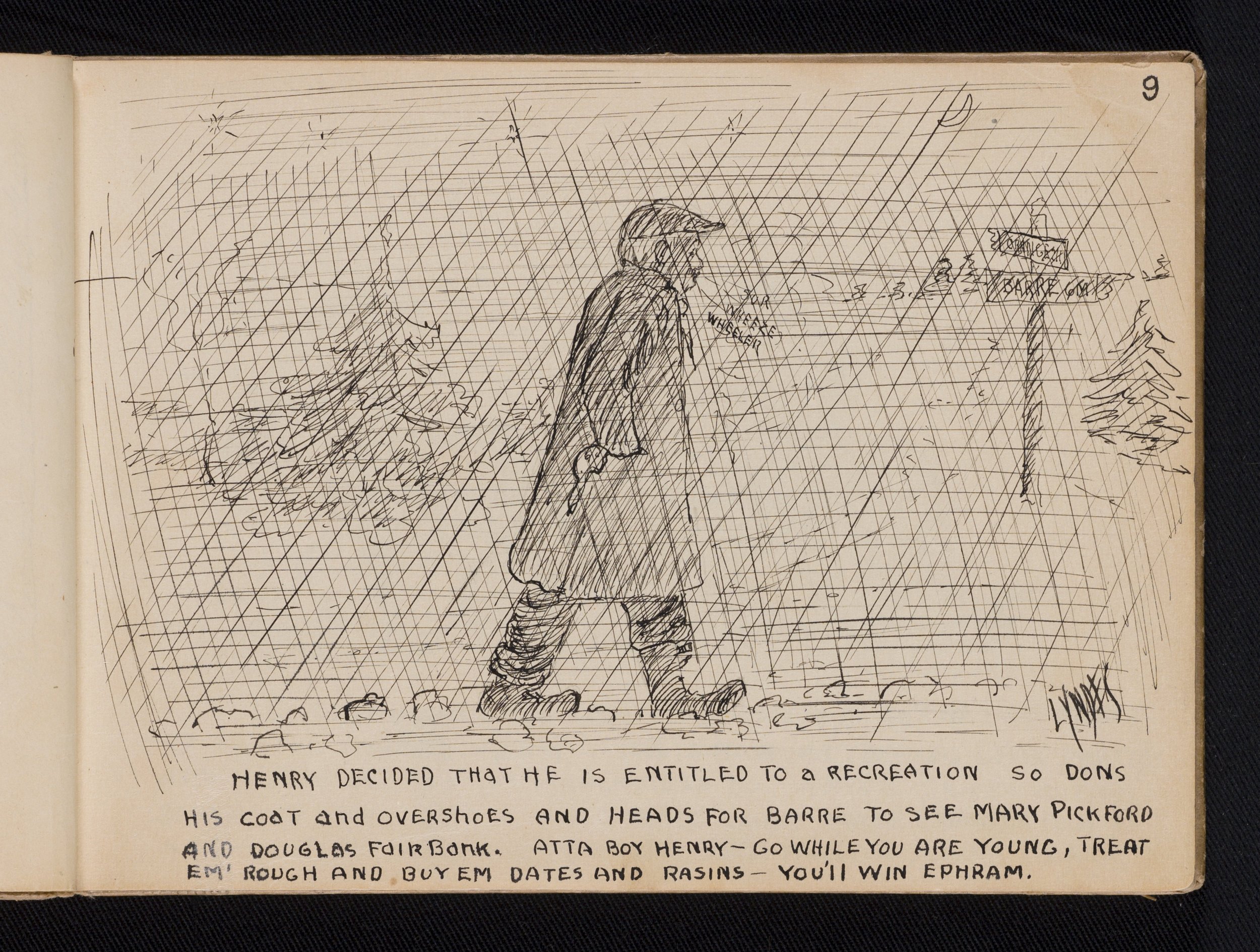

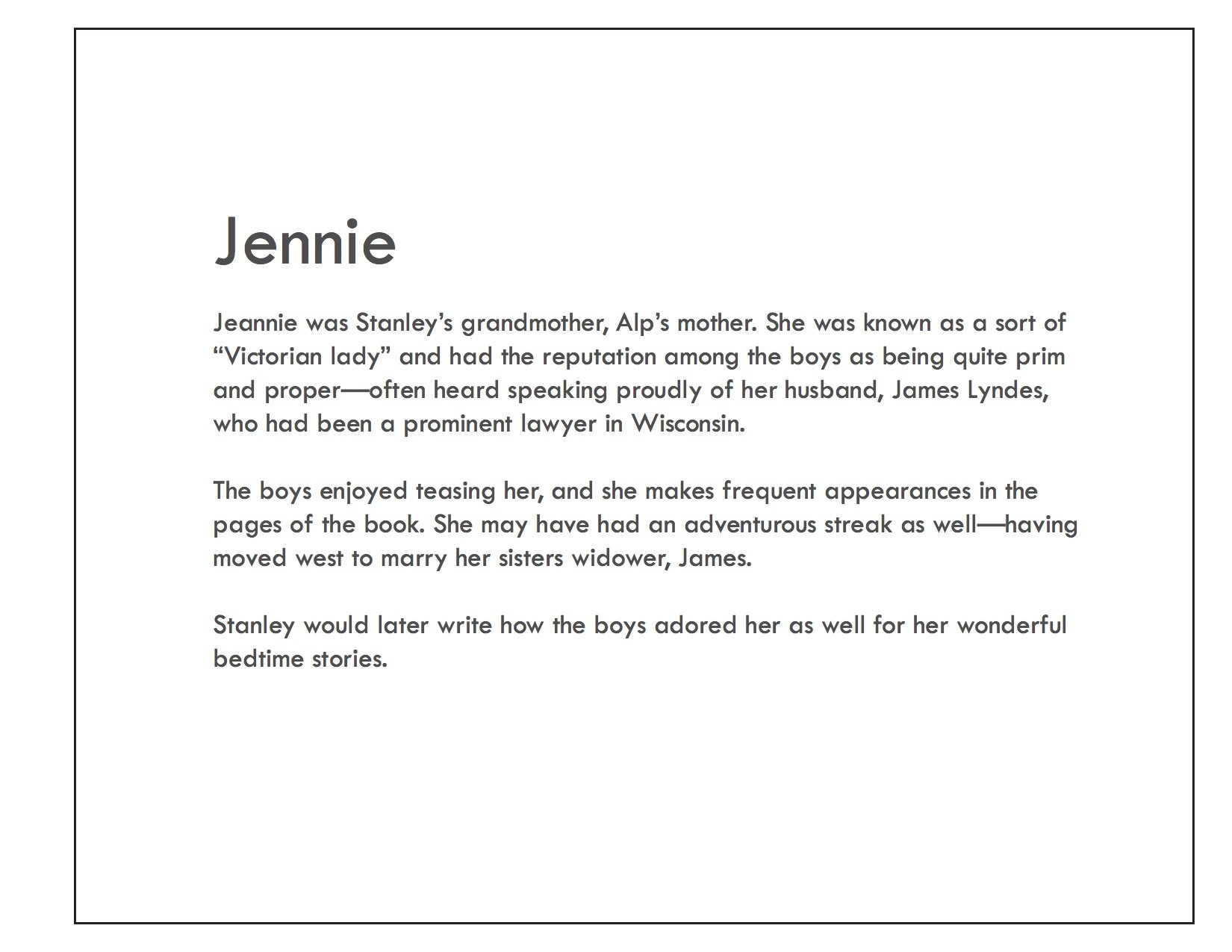

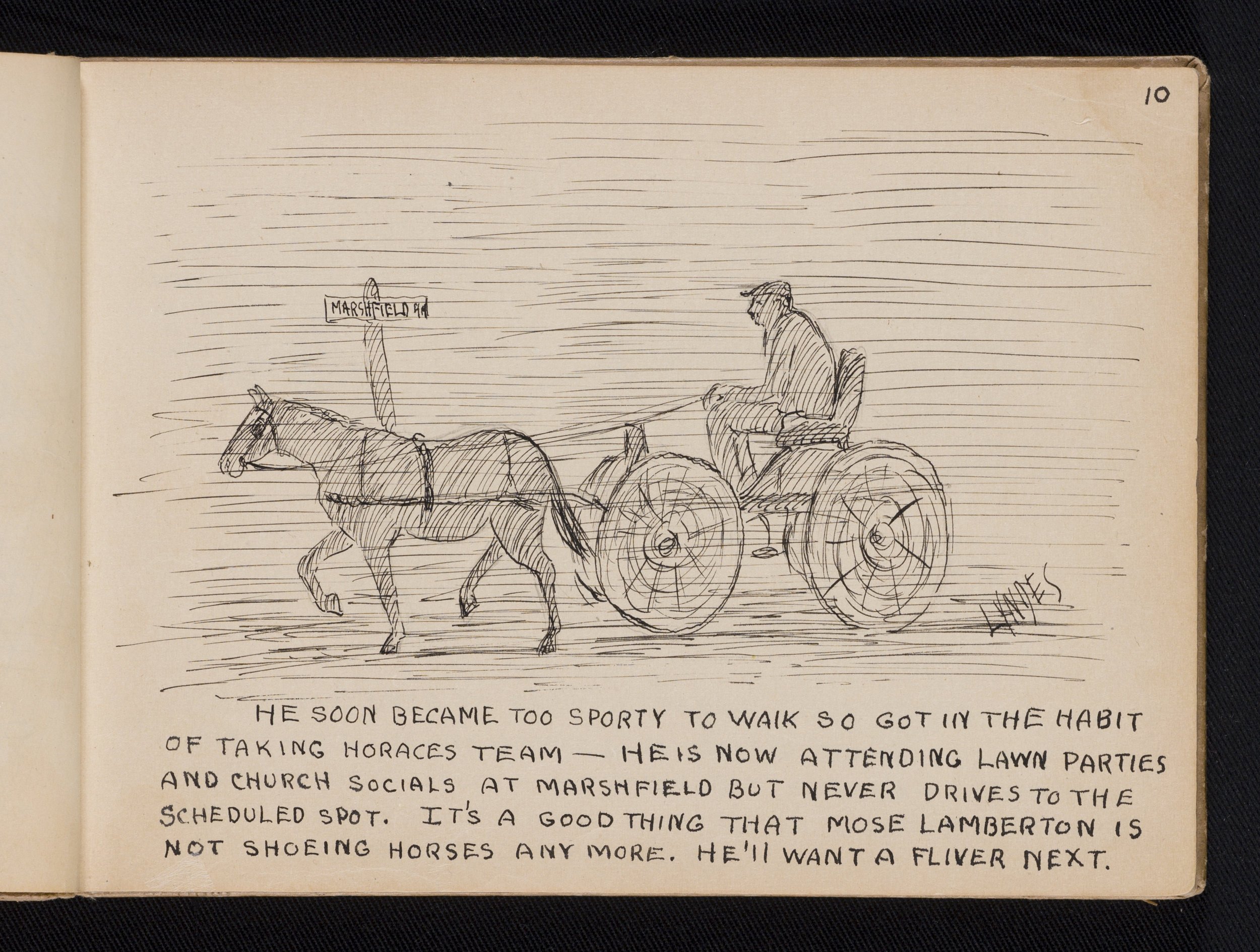

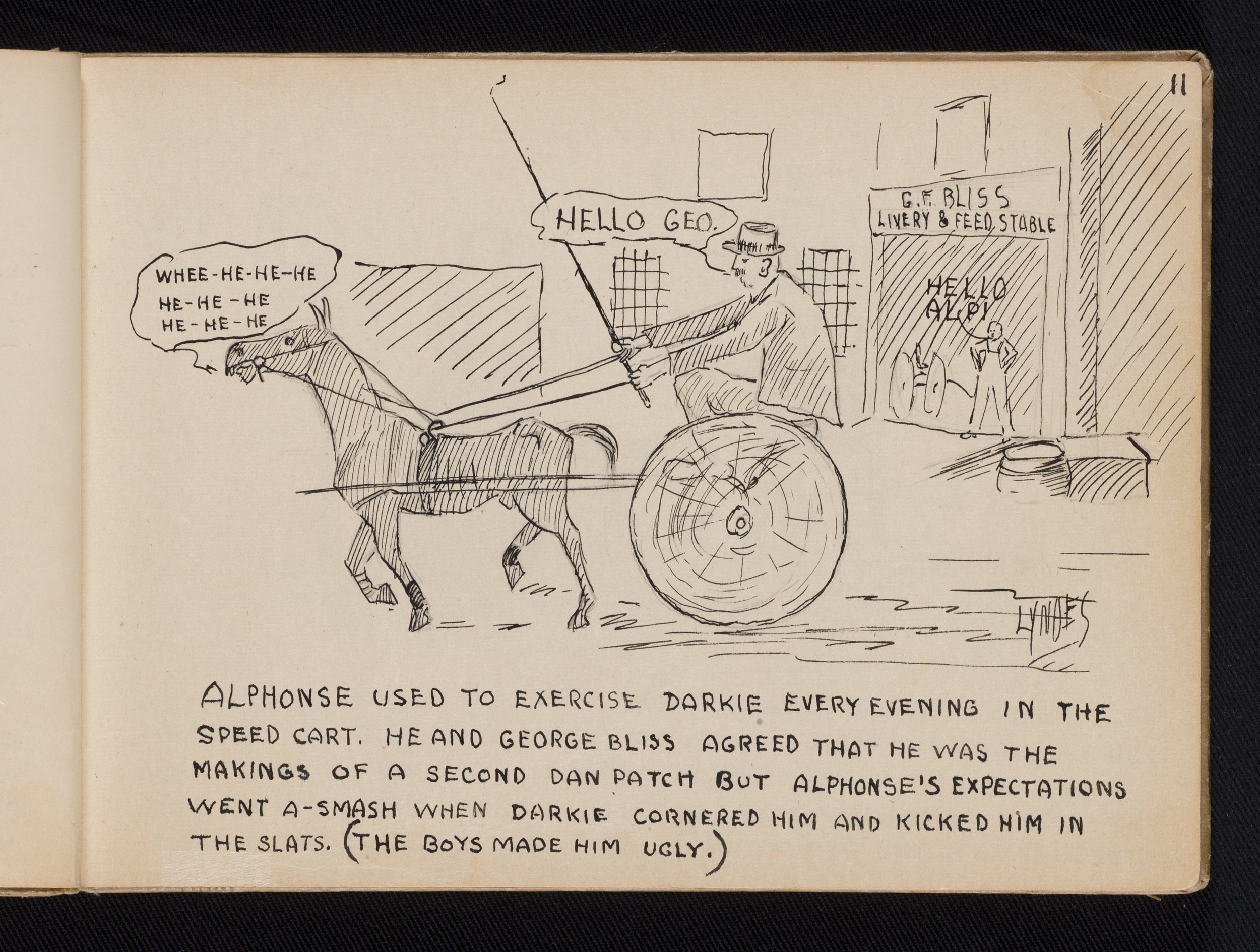

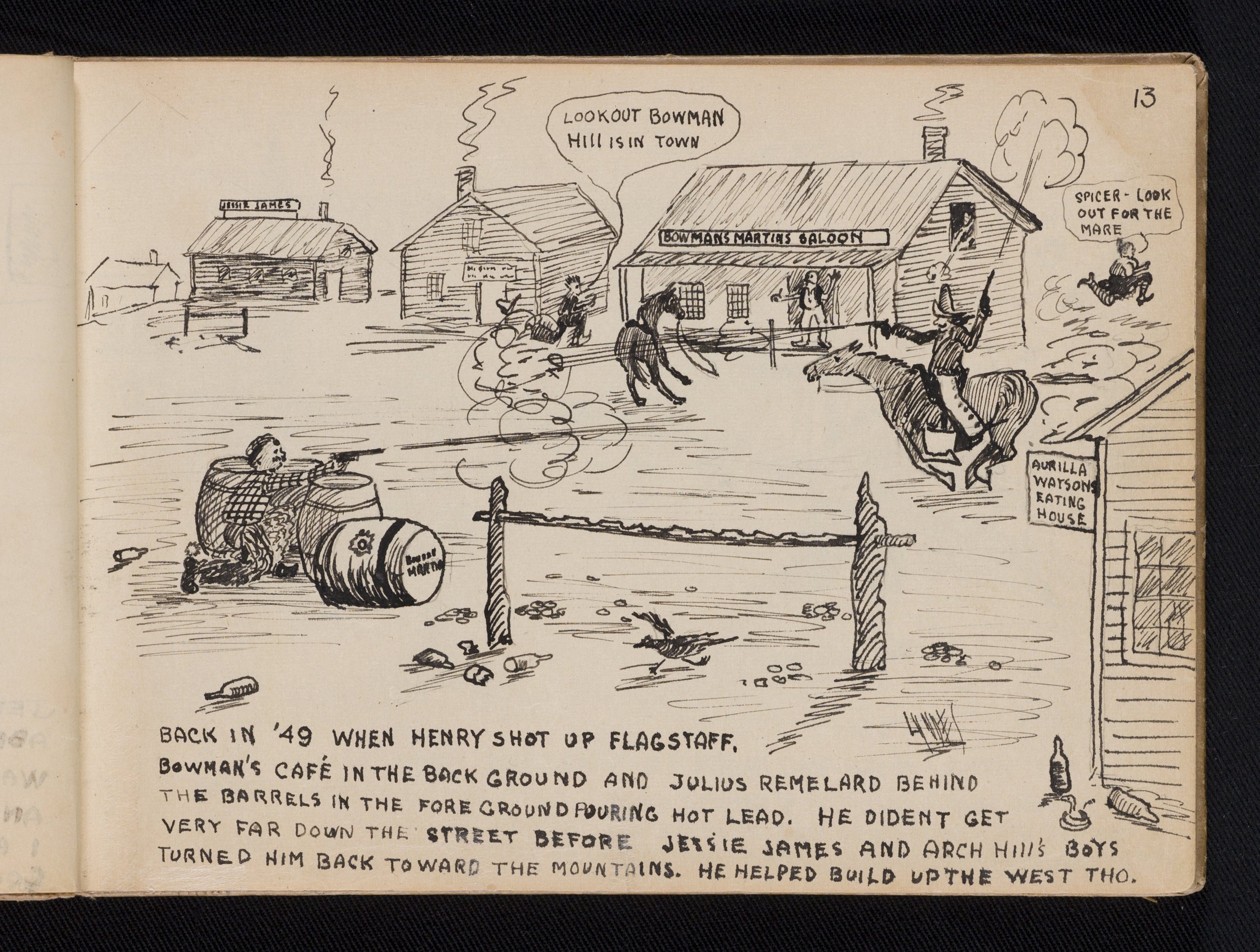

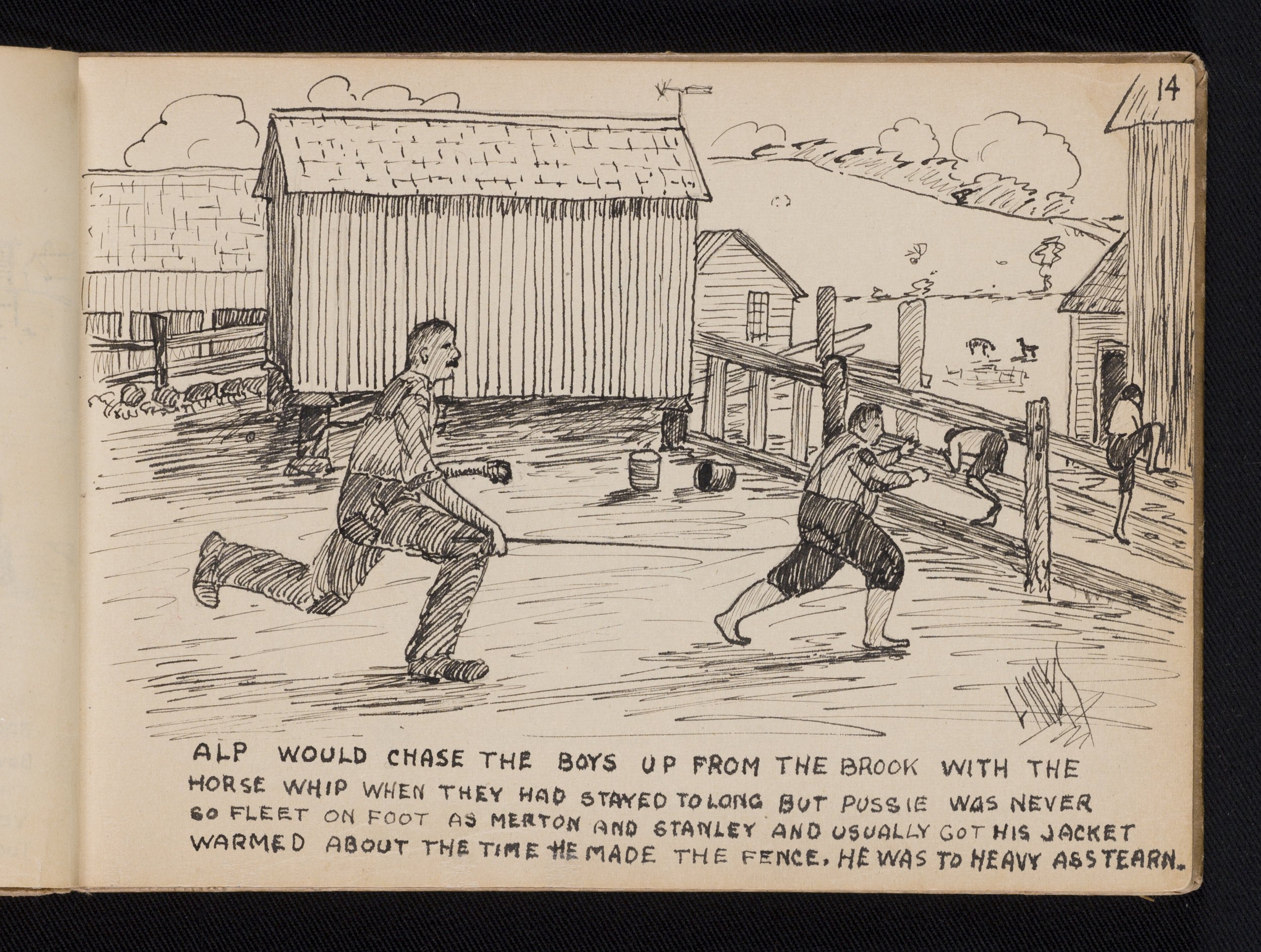

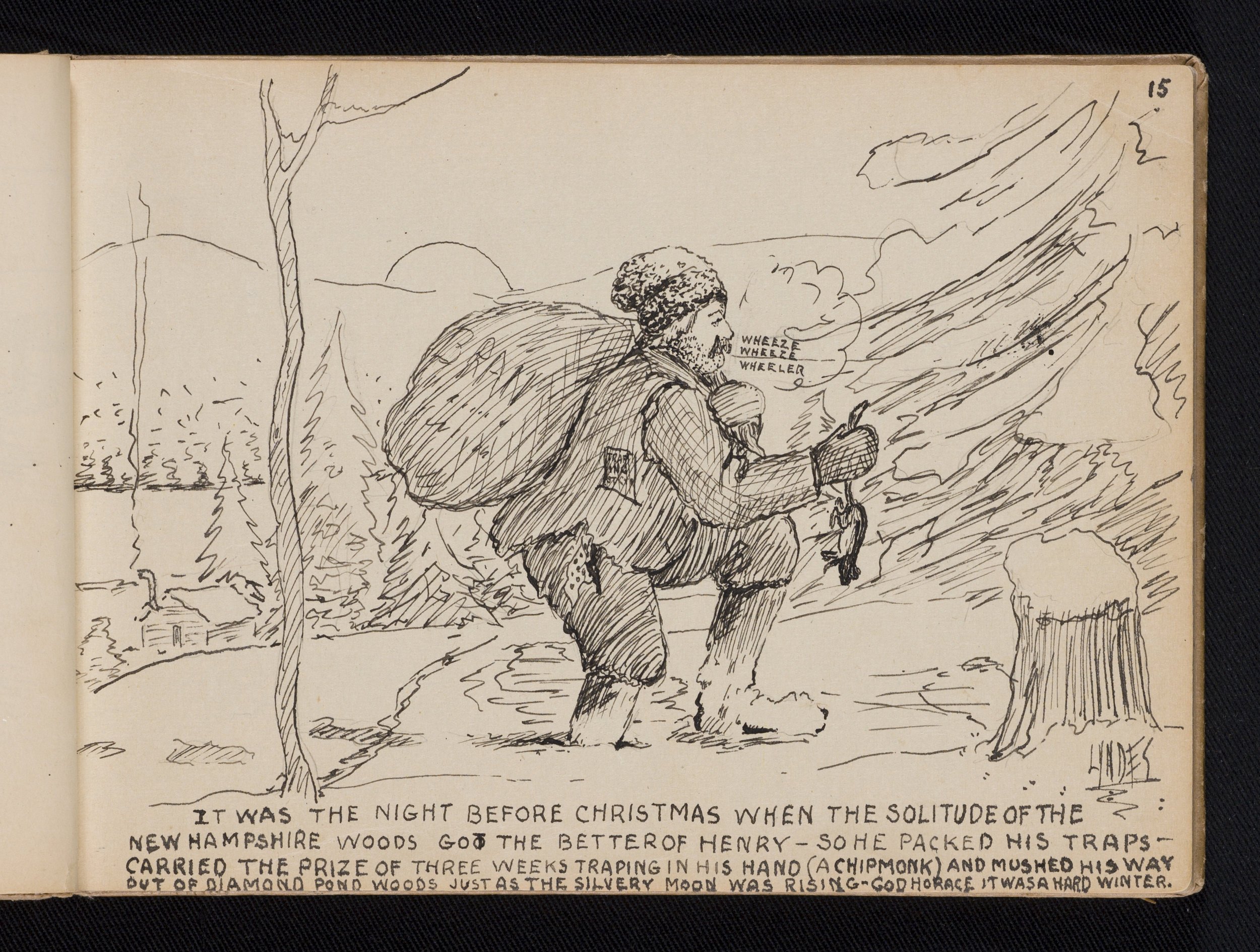

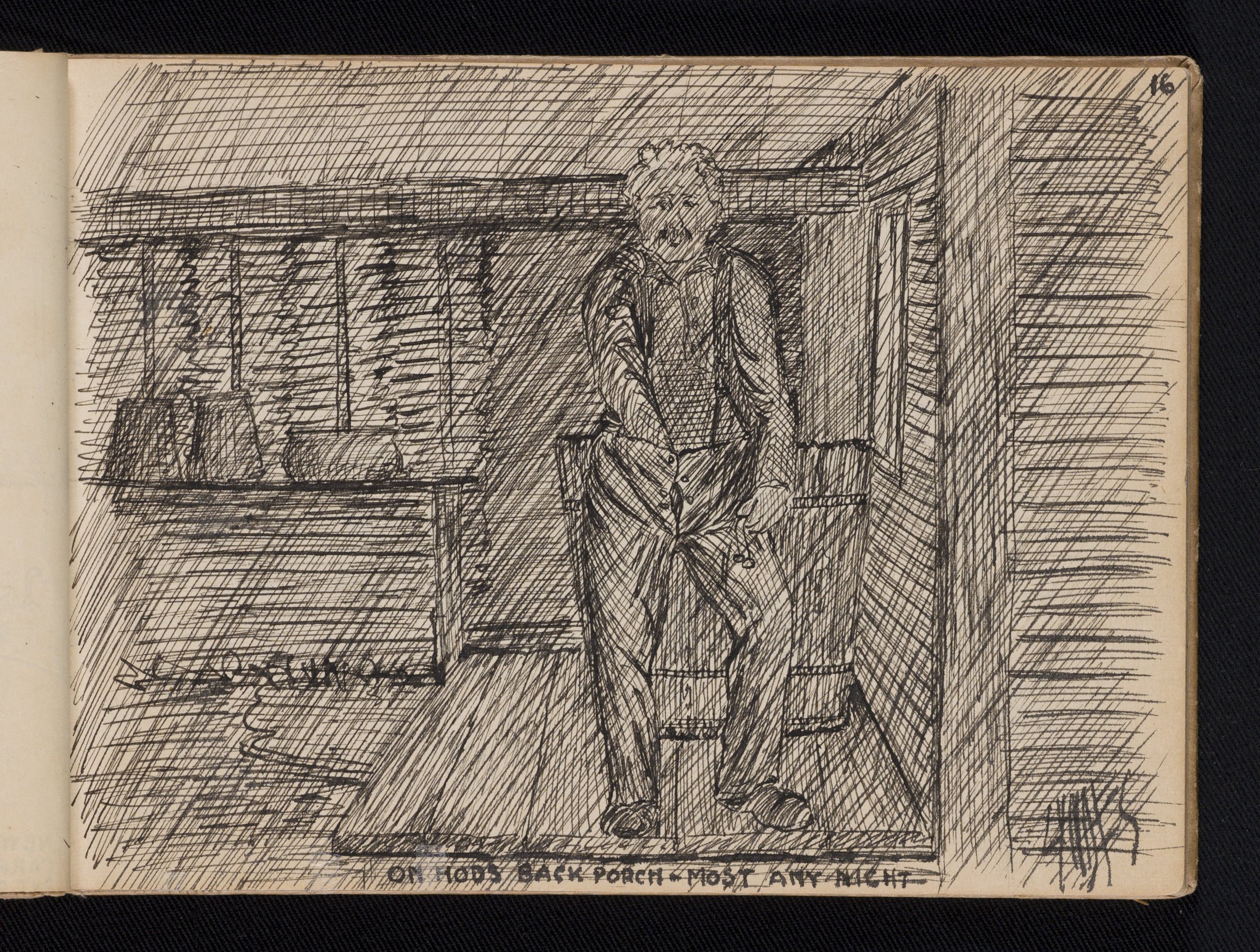

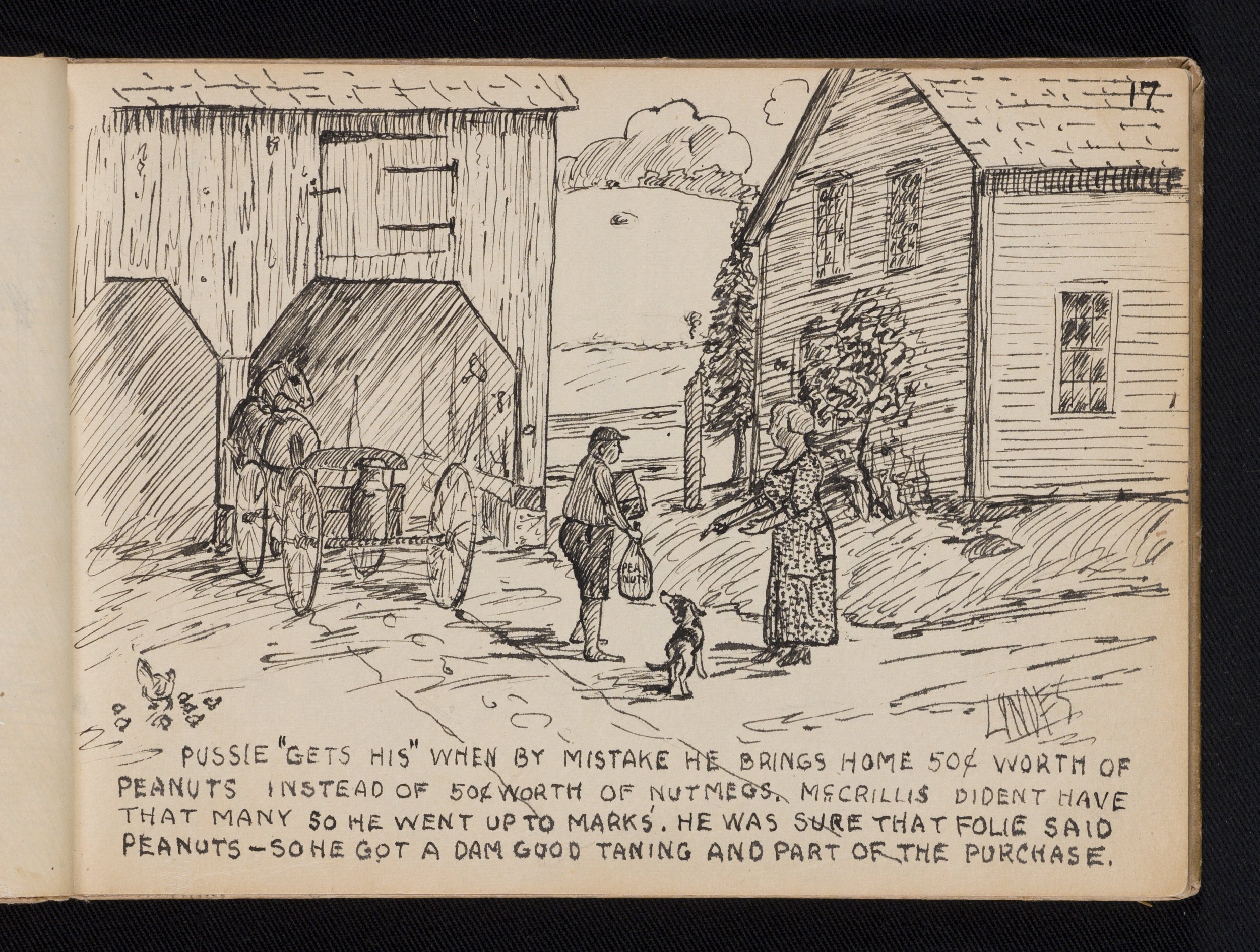

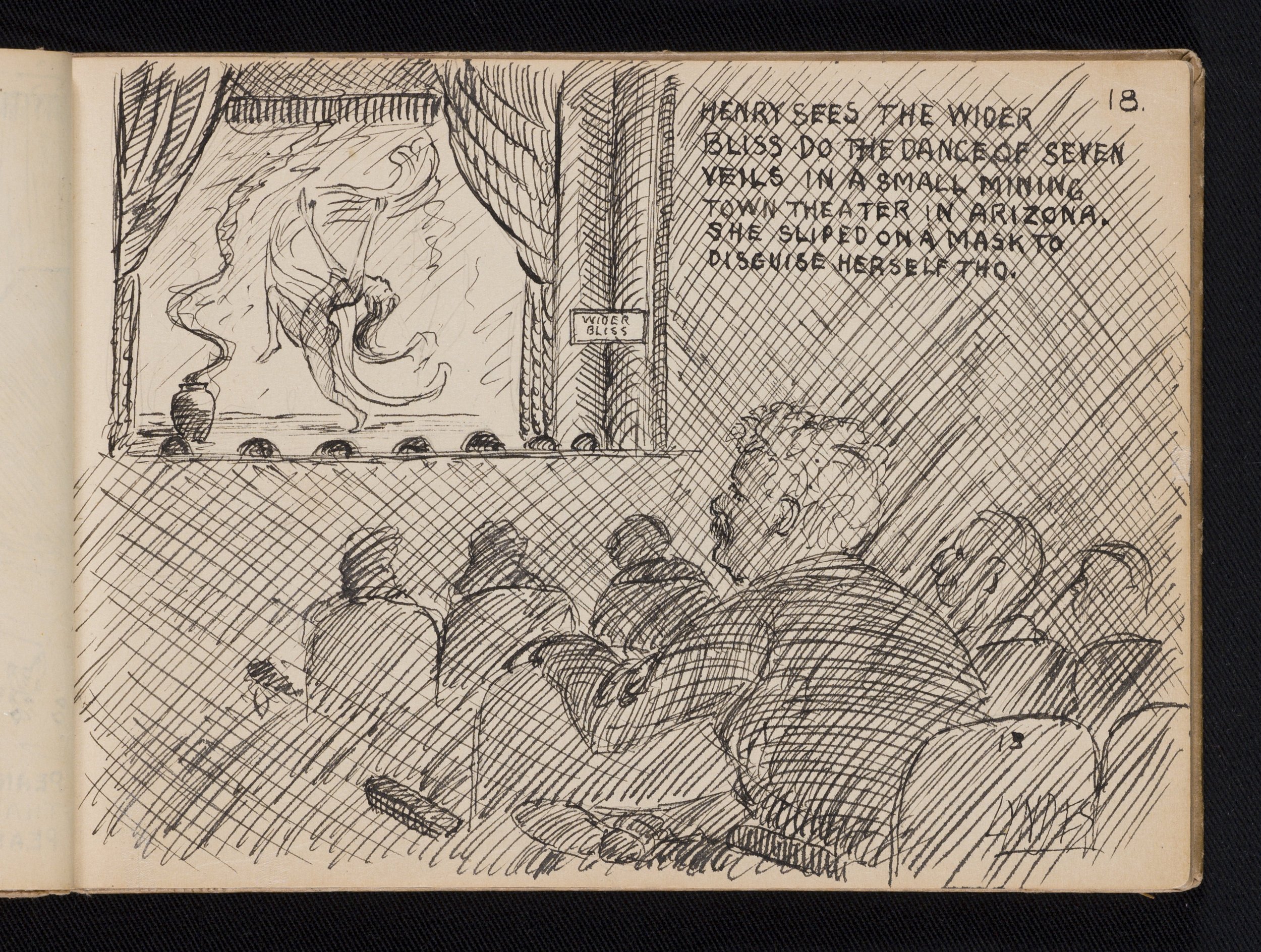

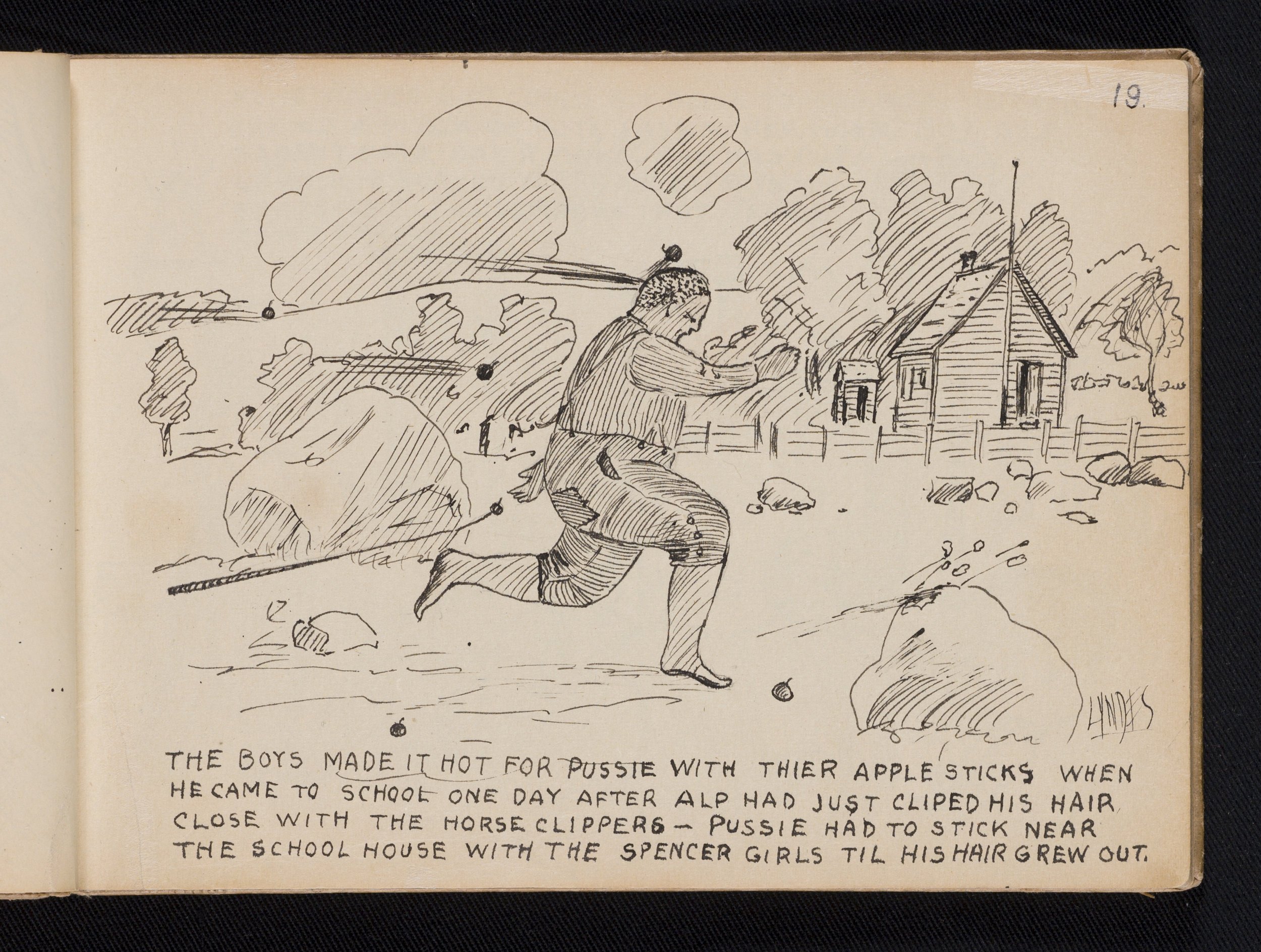

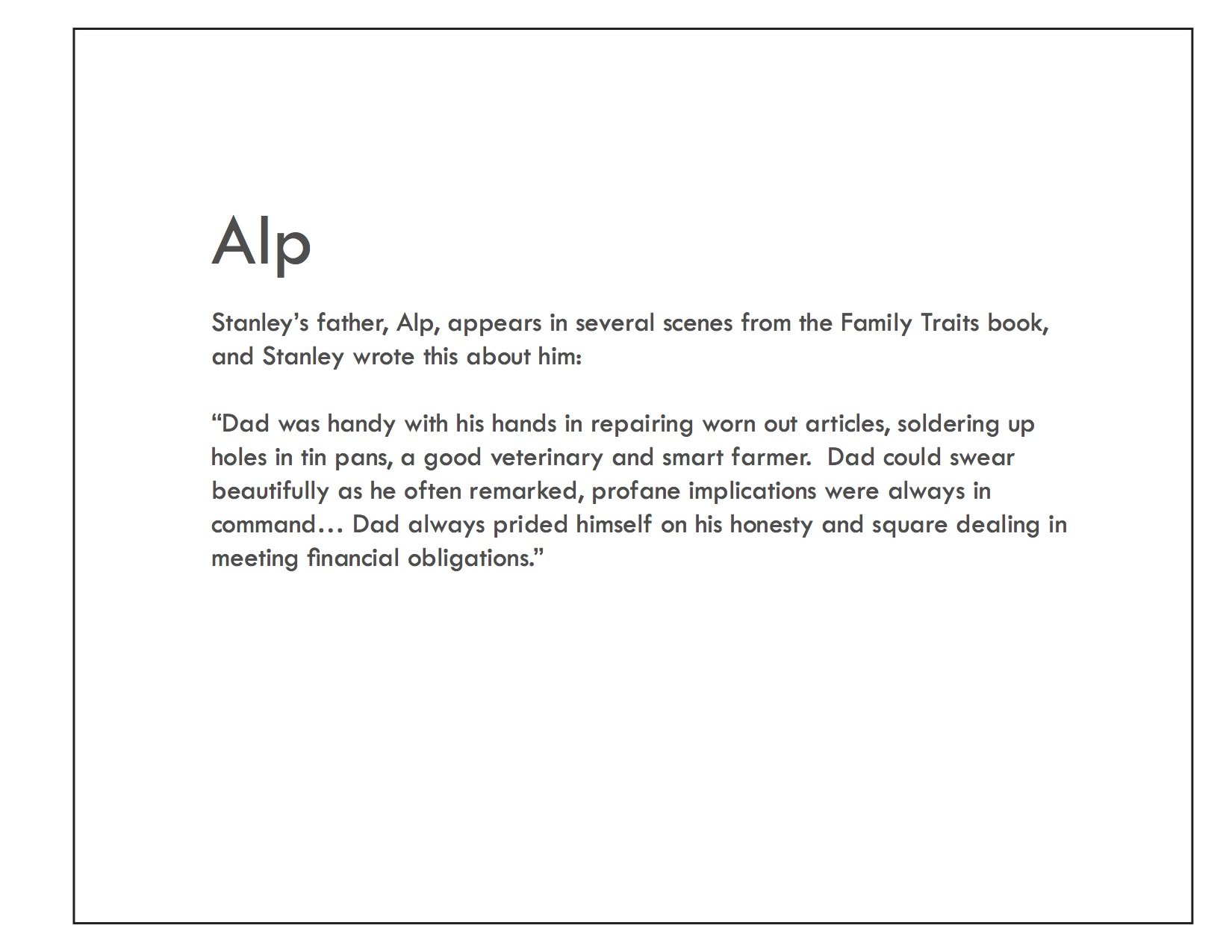

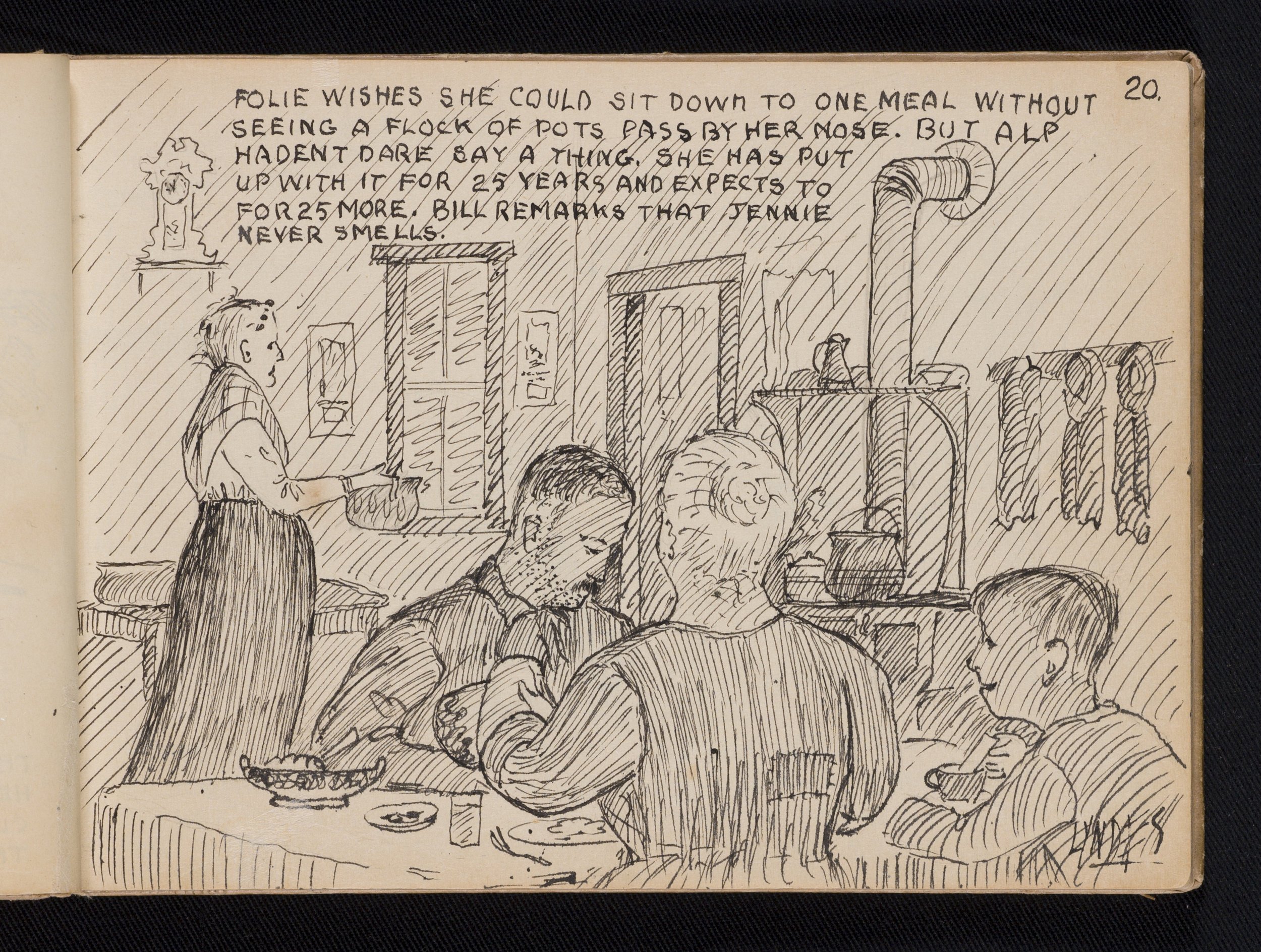

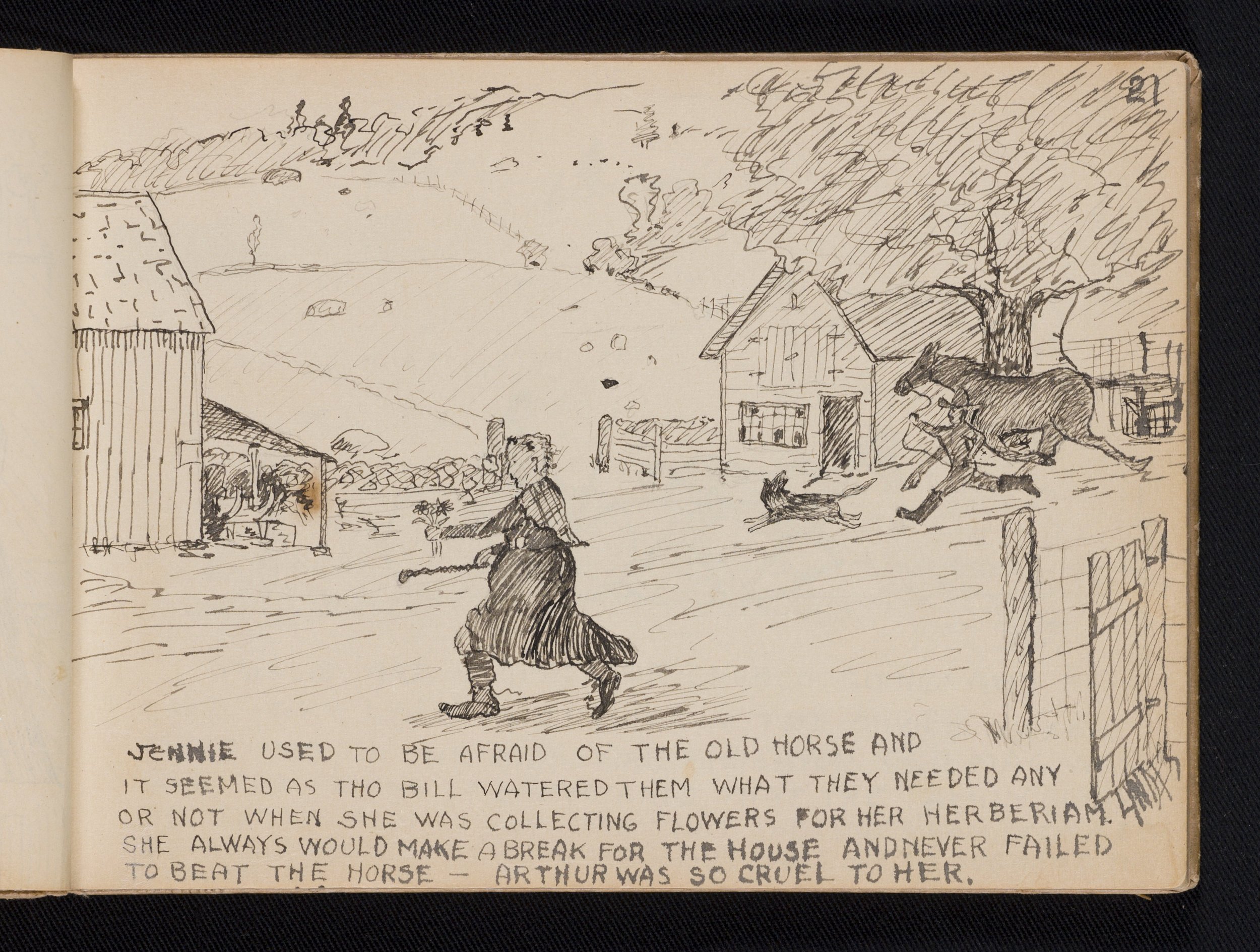

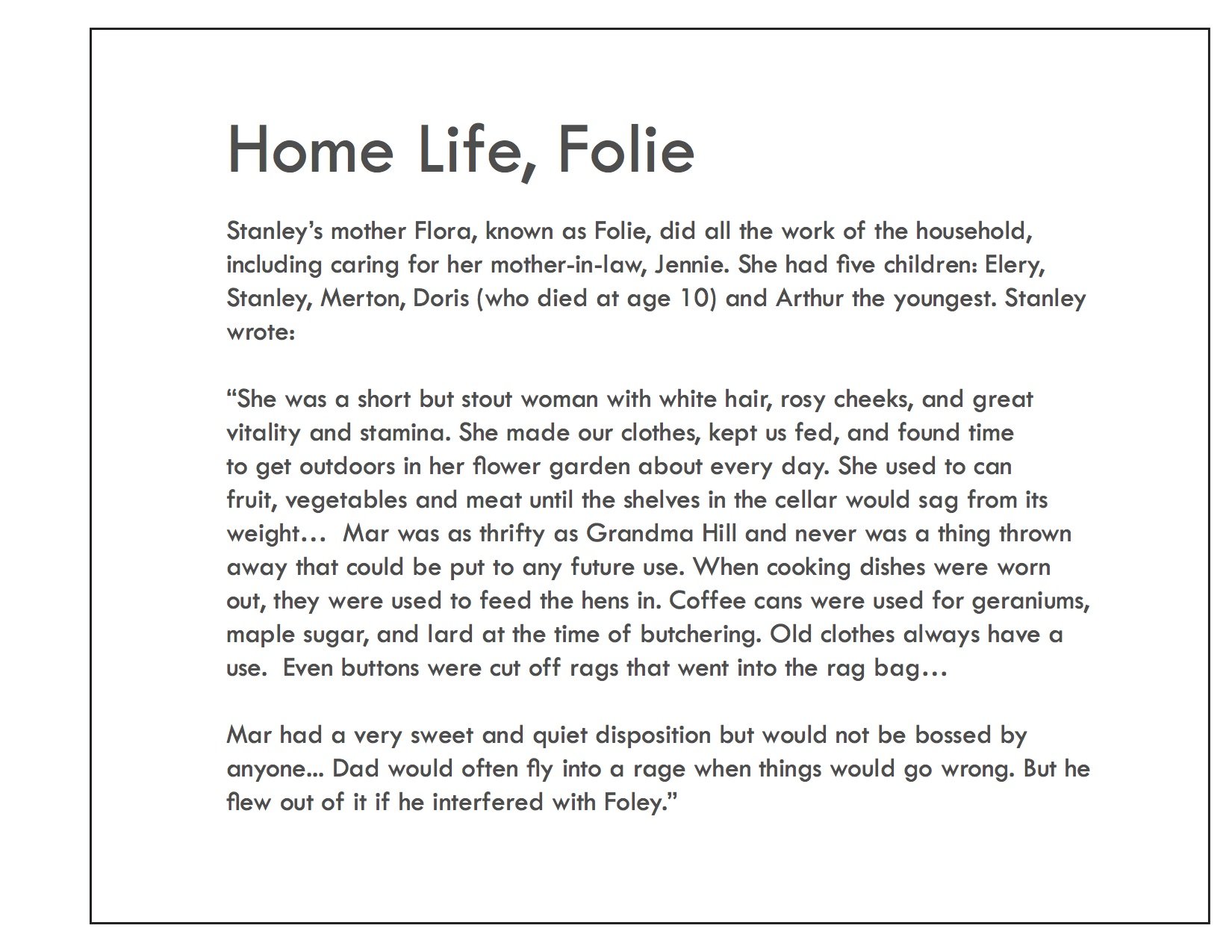

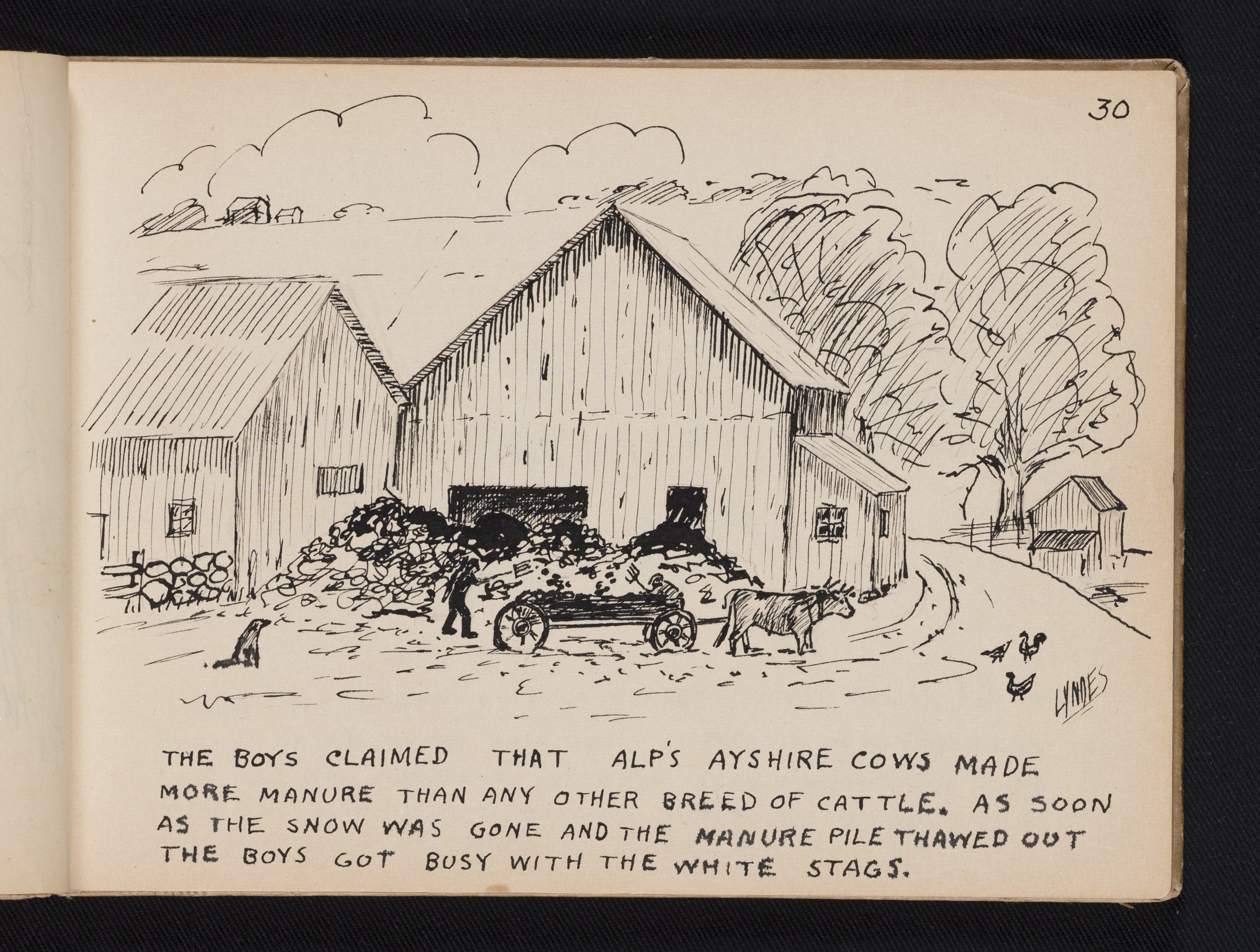

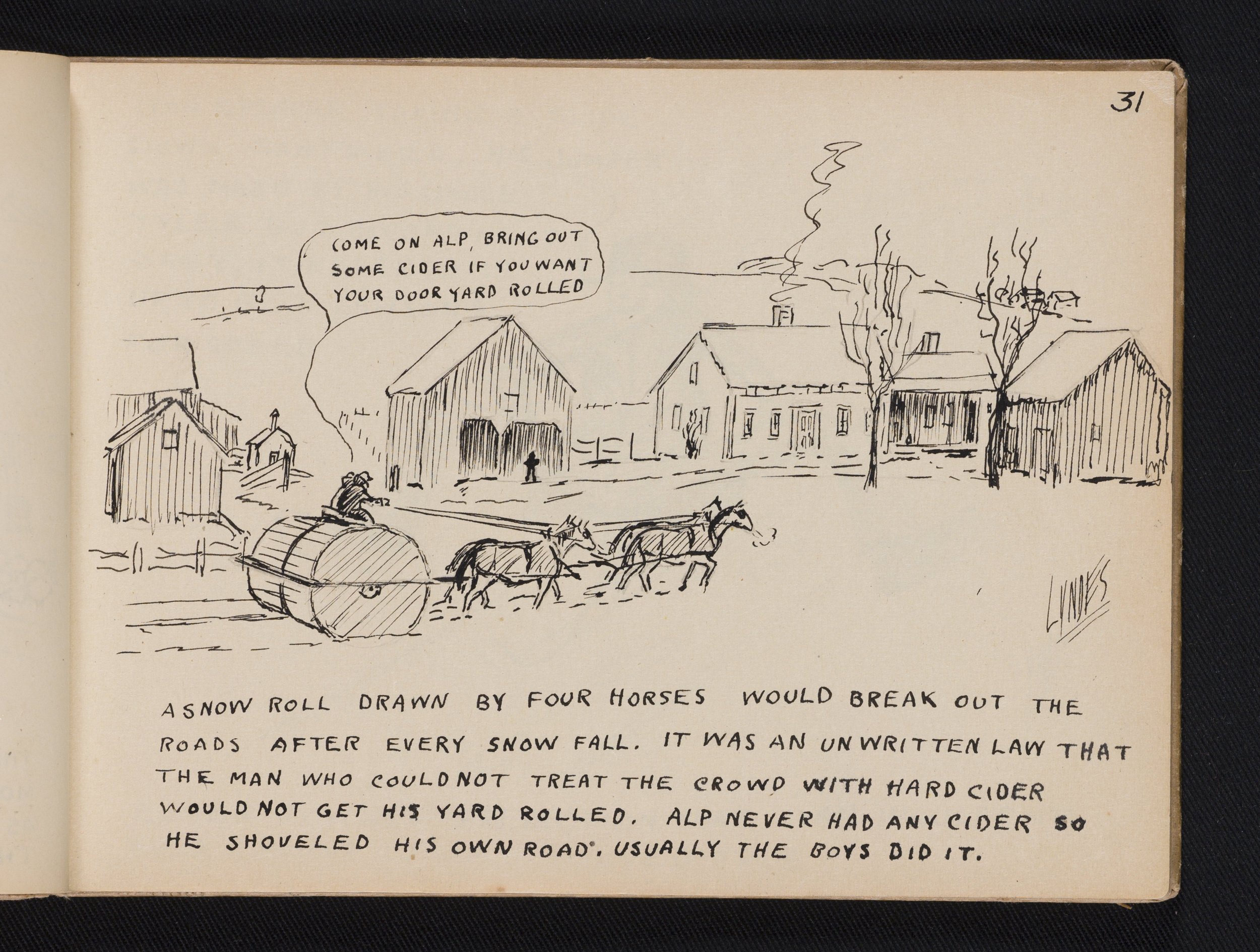

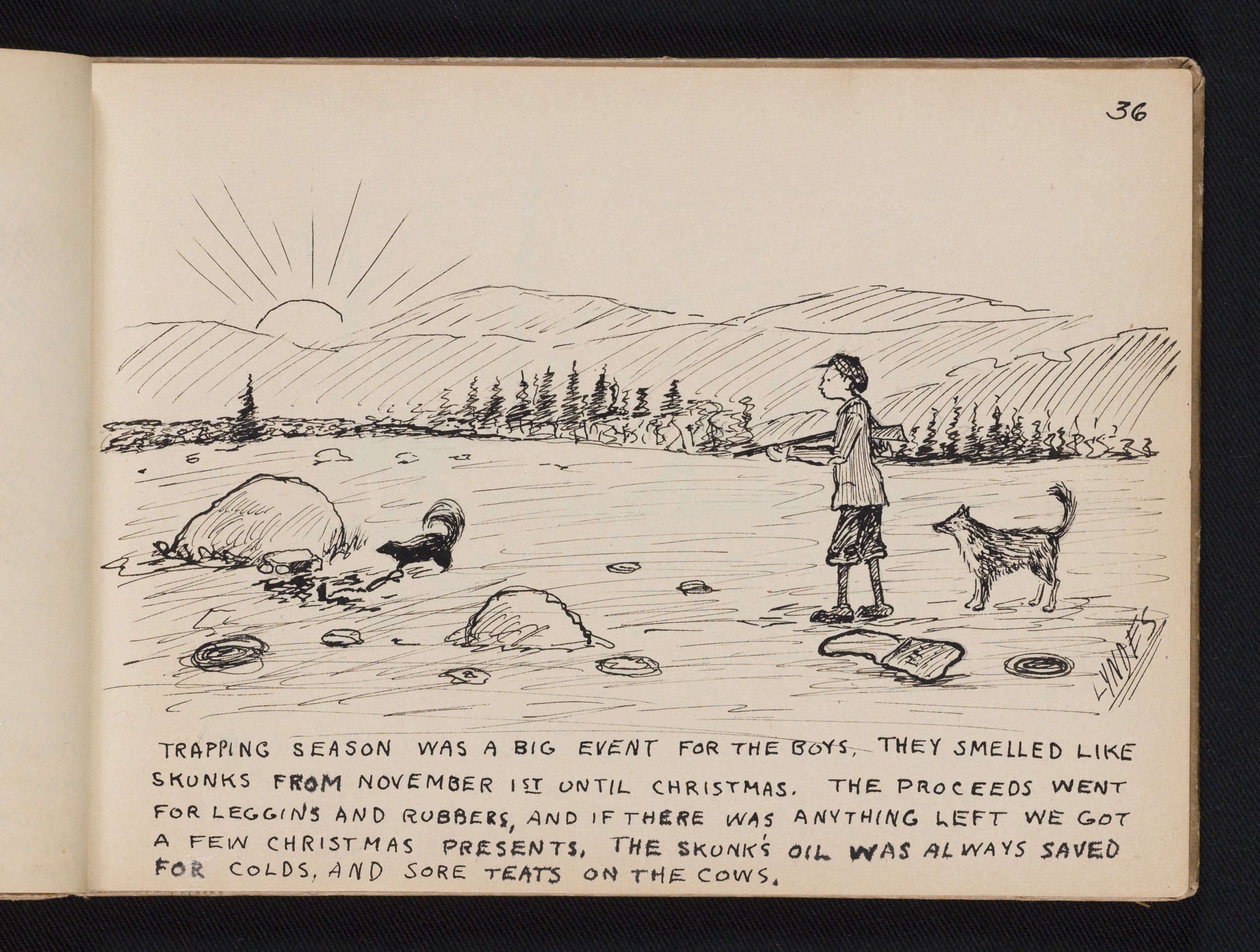

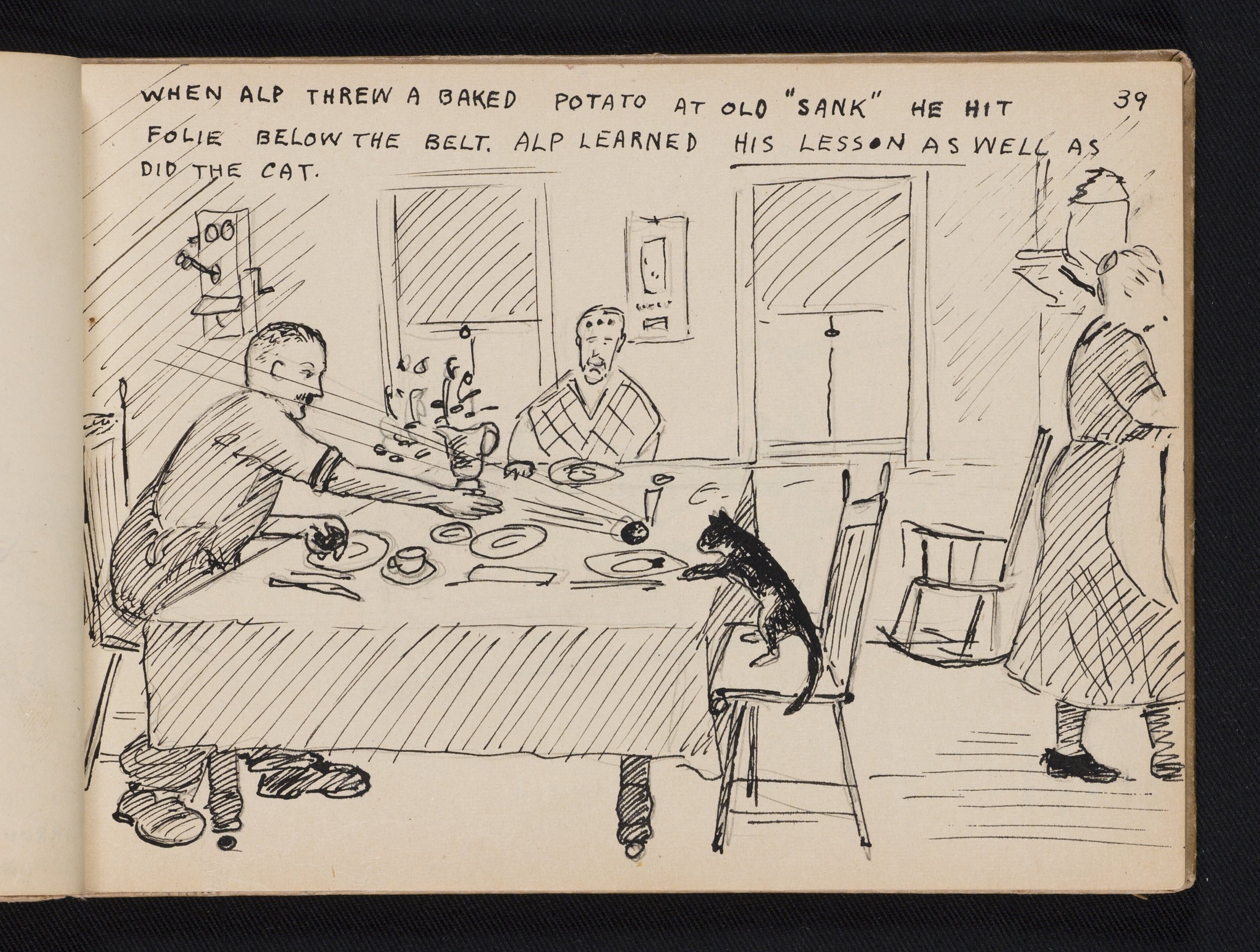

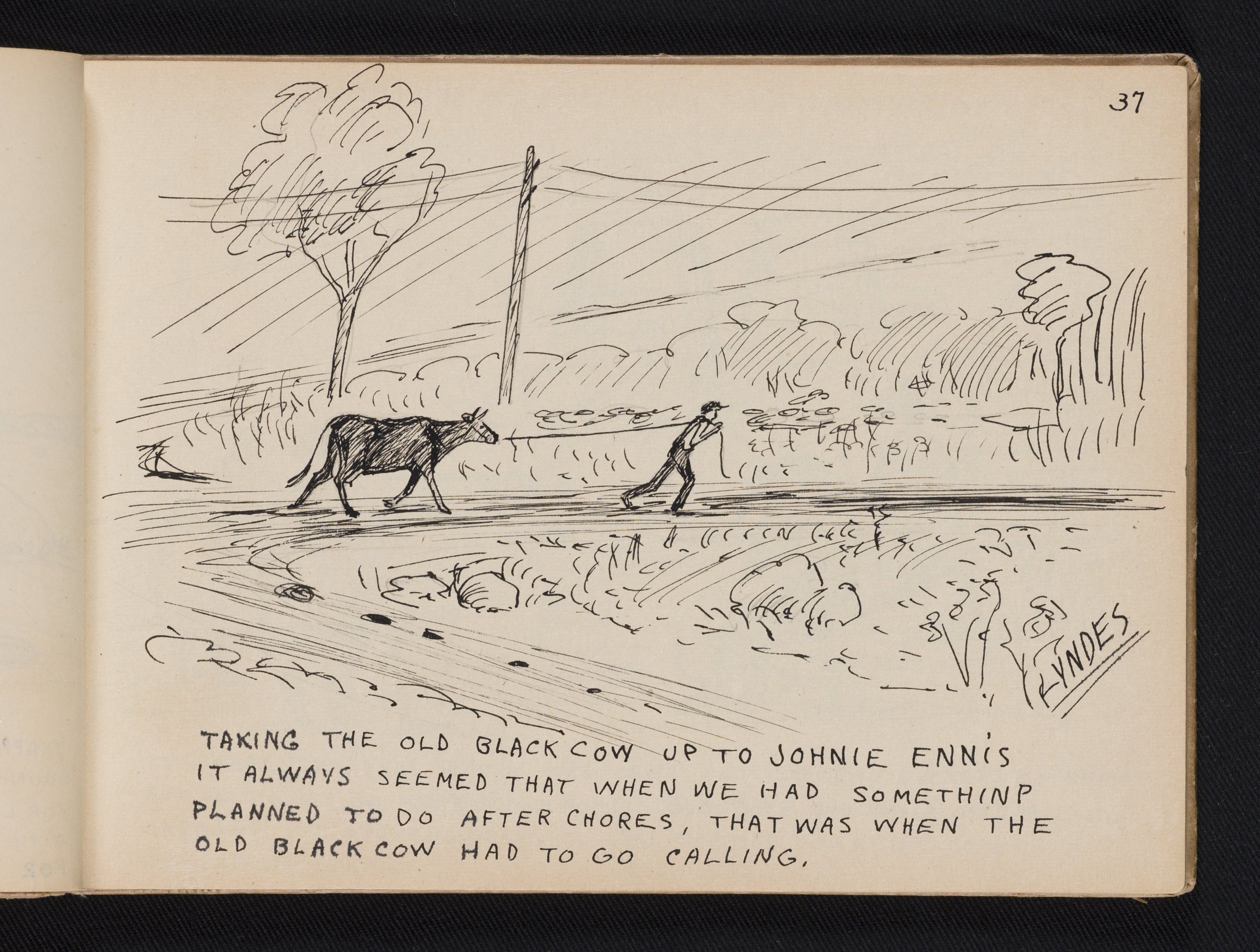

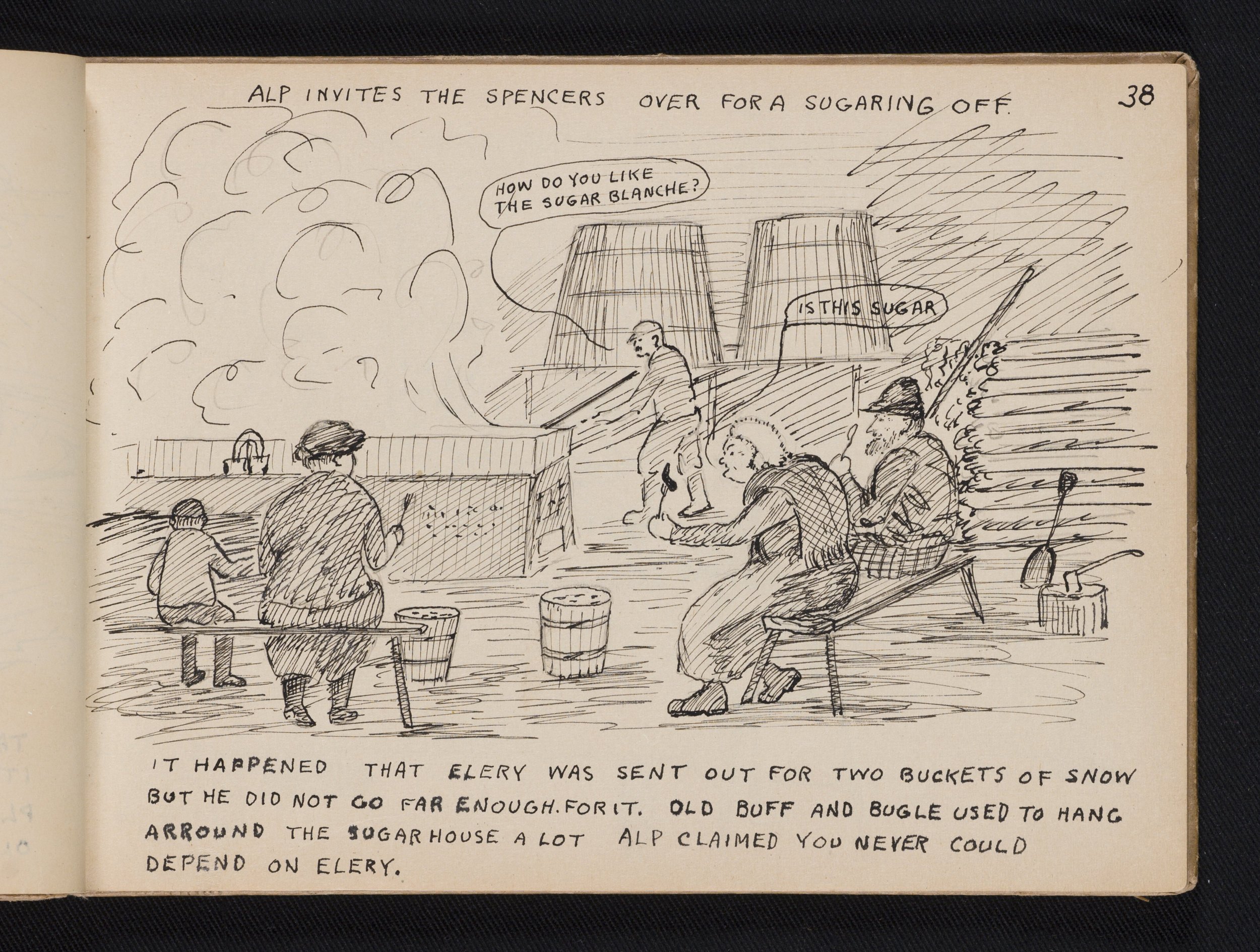

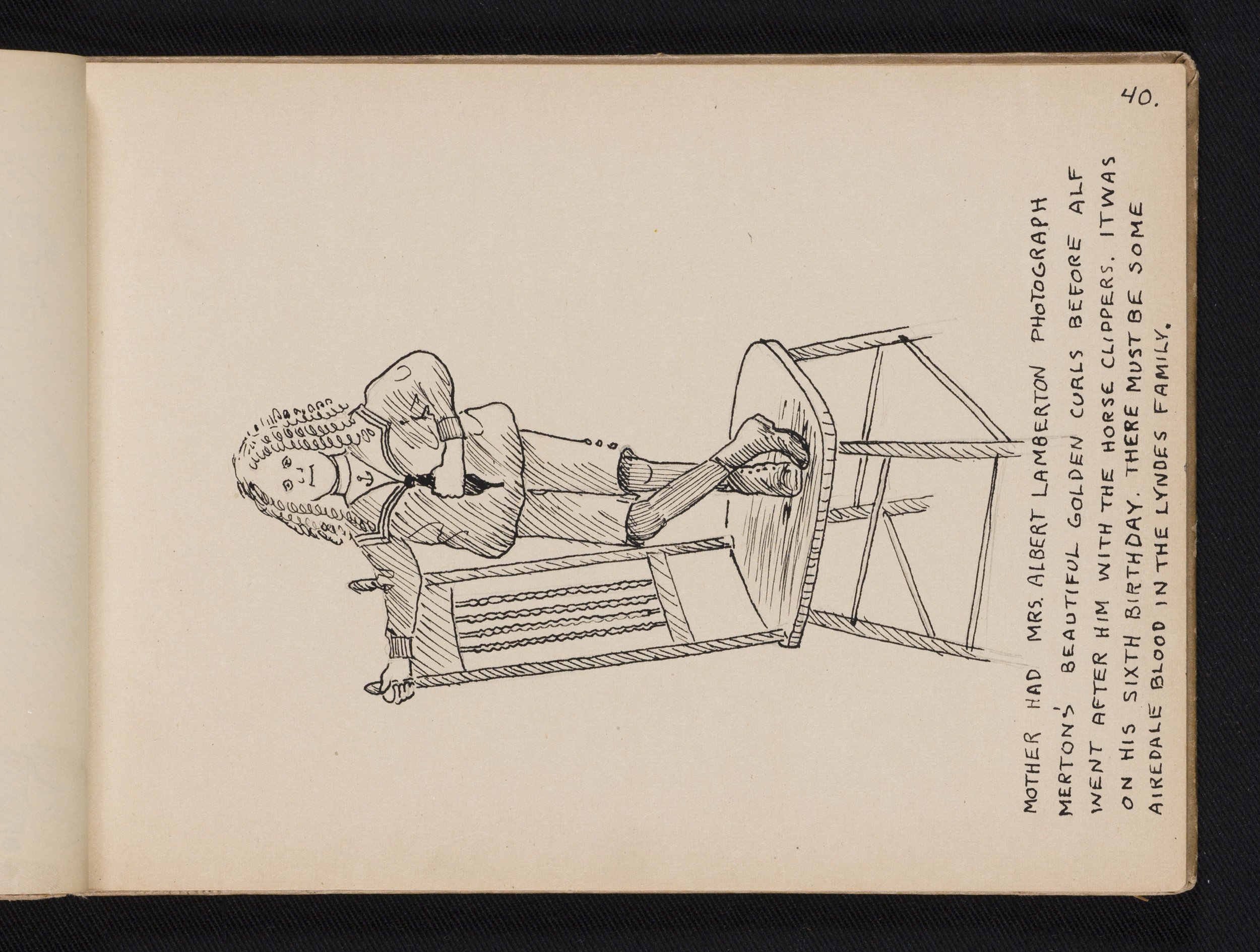

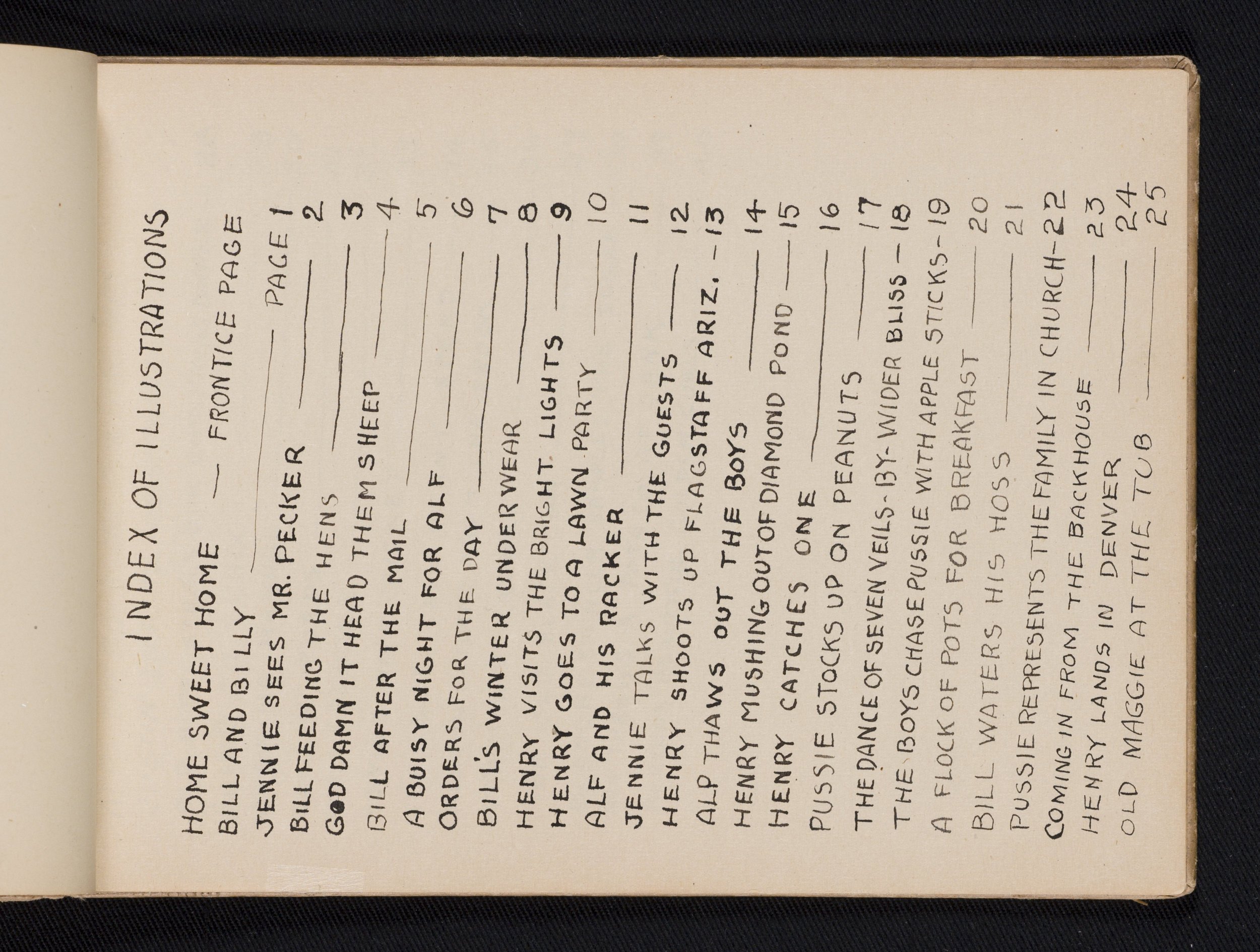

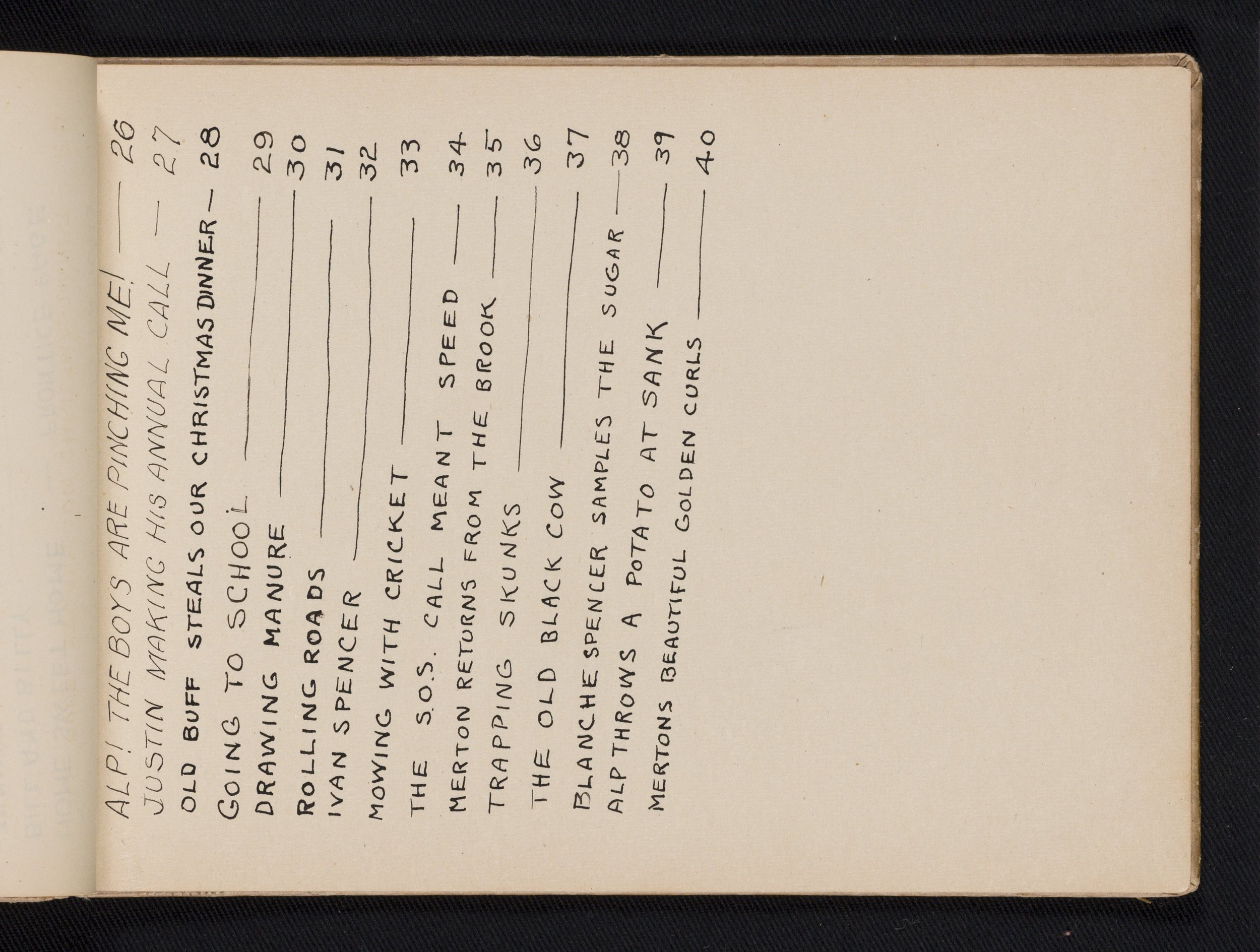

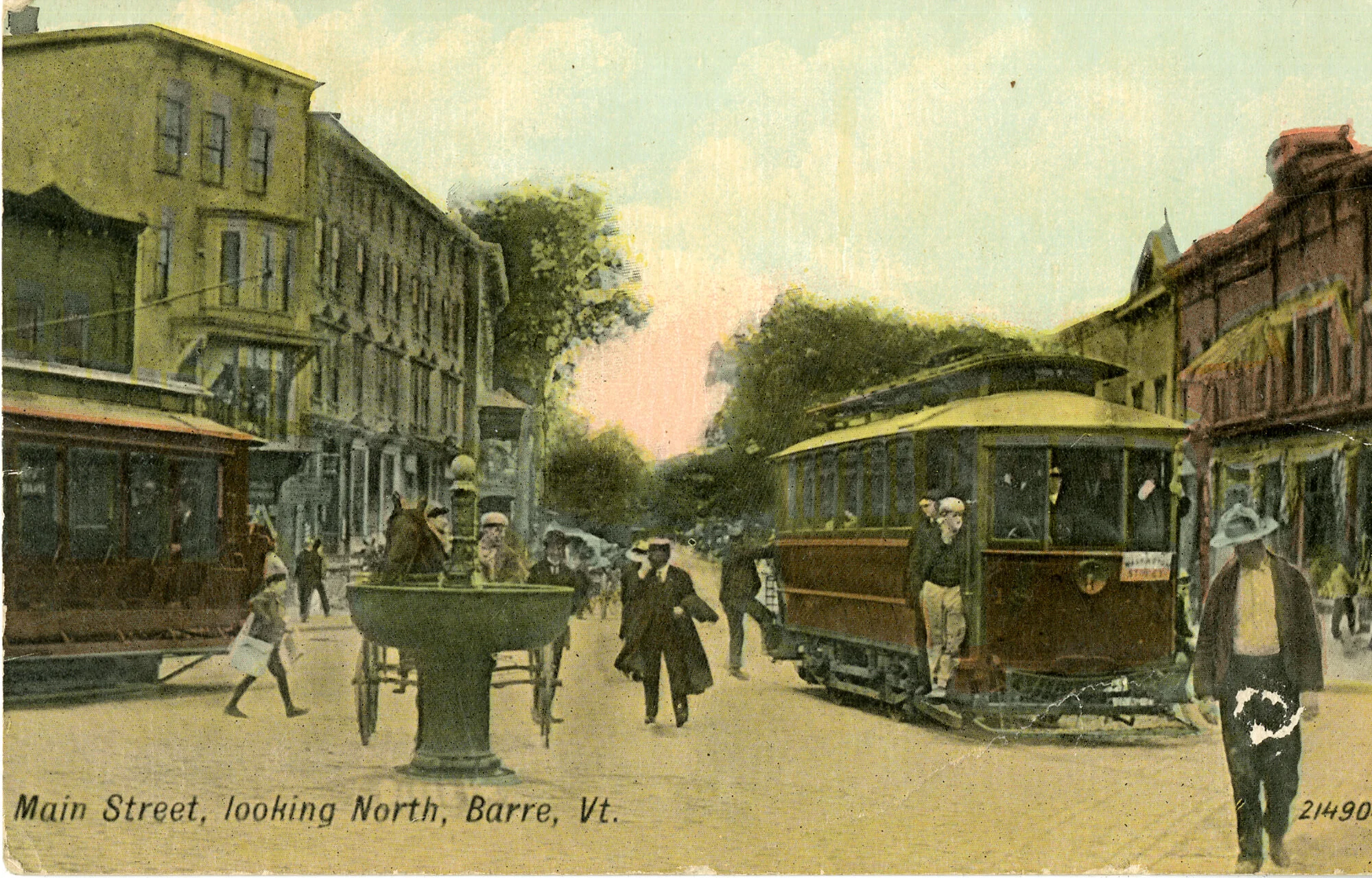

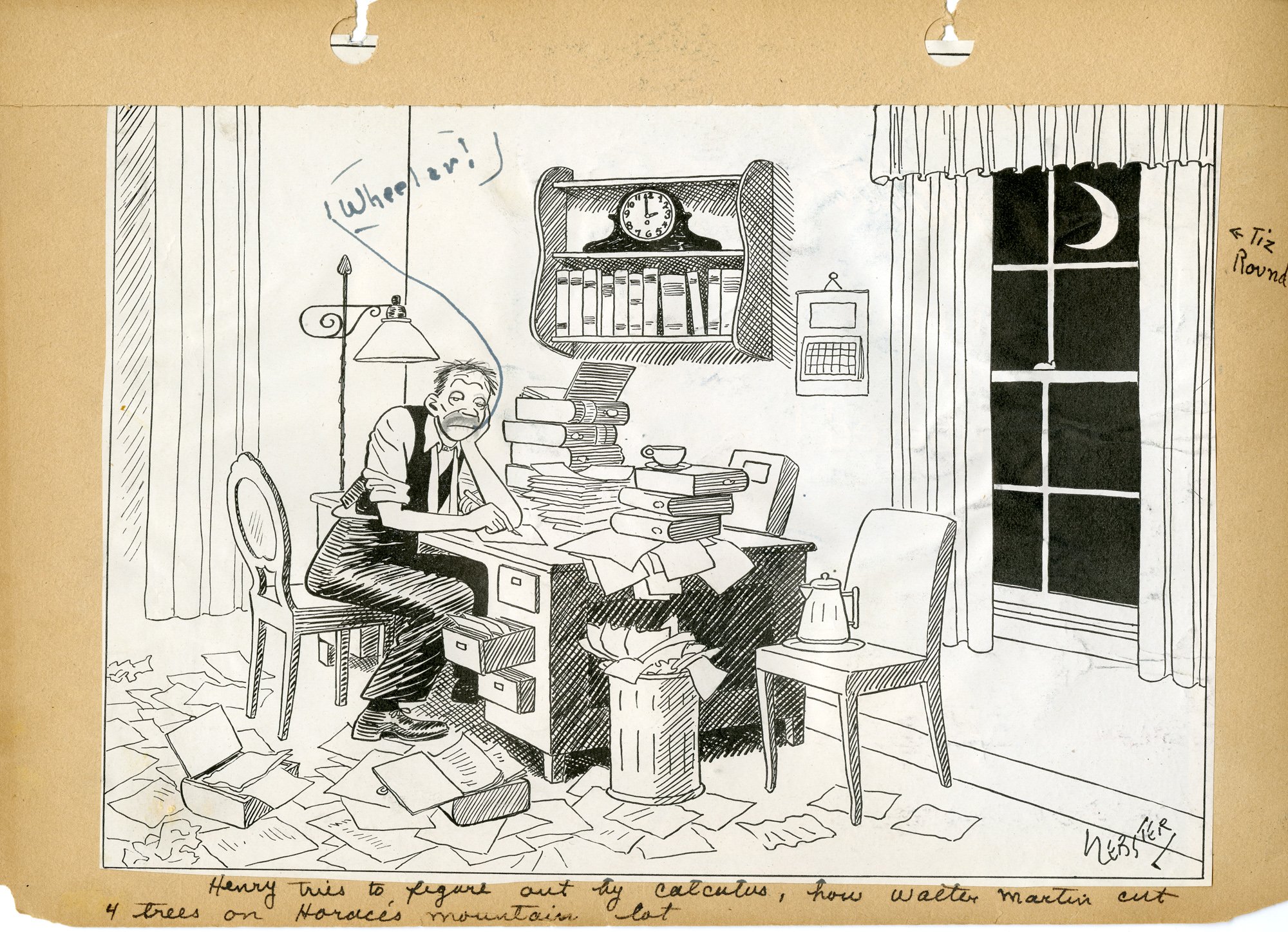

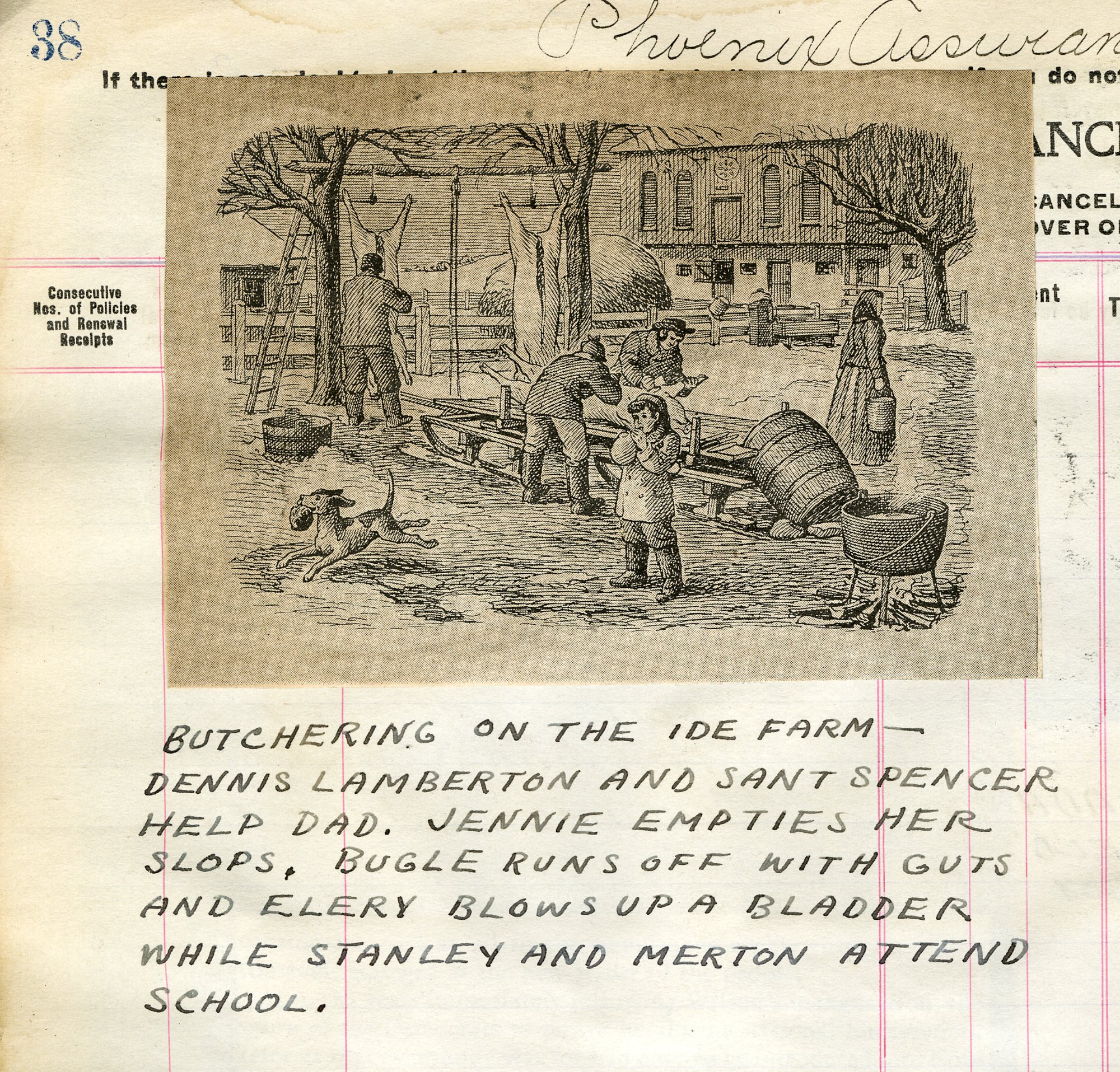

Among his legacy to his family, Stanley Lyndes left a small, handmade and worn book of his drawings, titled, Family Traits. The sketches of his family and their neighbors wryly depict life on small farms in Calais, Cabot, and Marshfield in the years between the turn of the century and WWI.

While studying at Pratt Institute, Stanley took a bookbinding class and made the small blank book. His friends, who liked his stories of life back on the farm, encouraged him to use it for sketches of life at home.

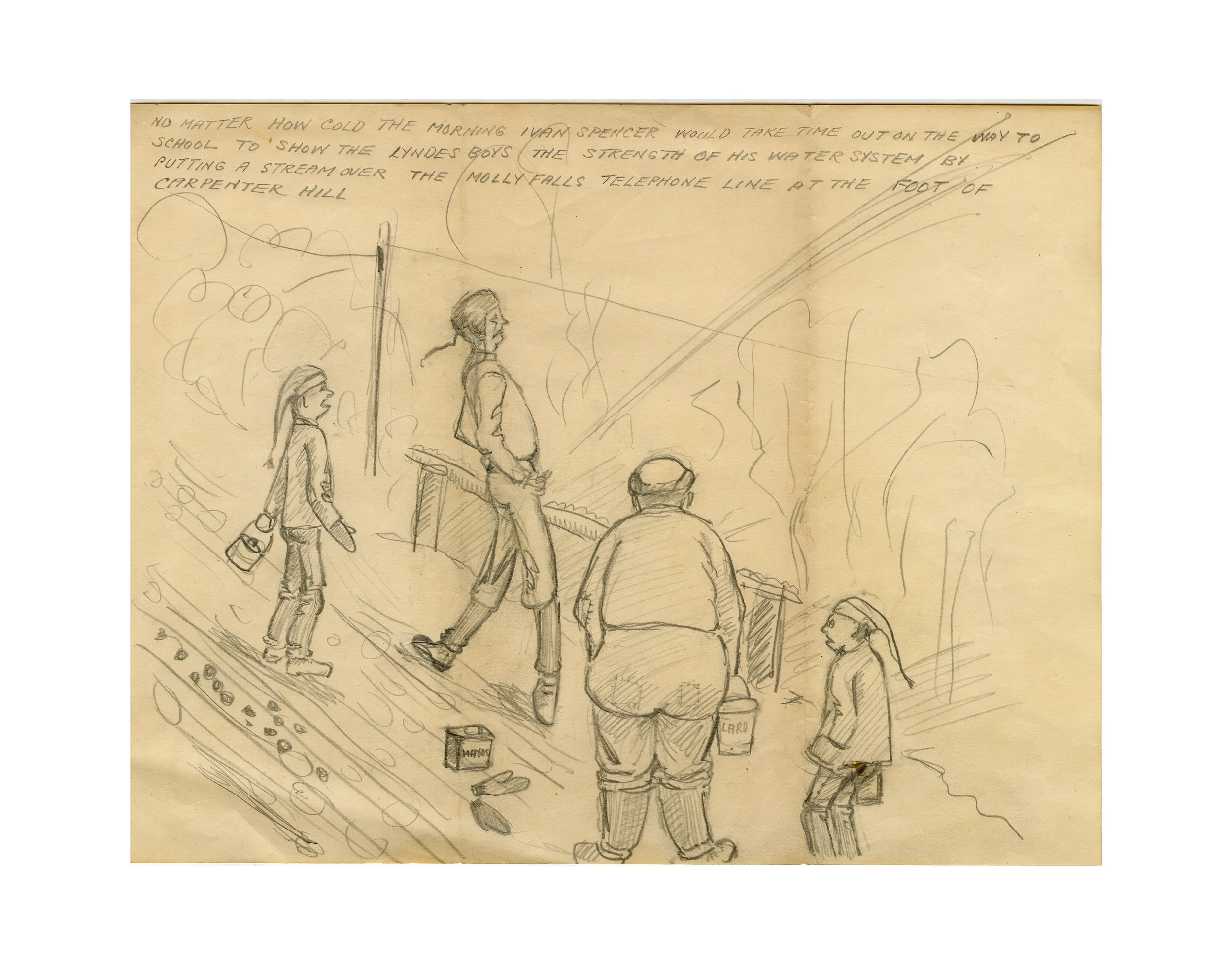

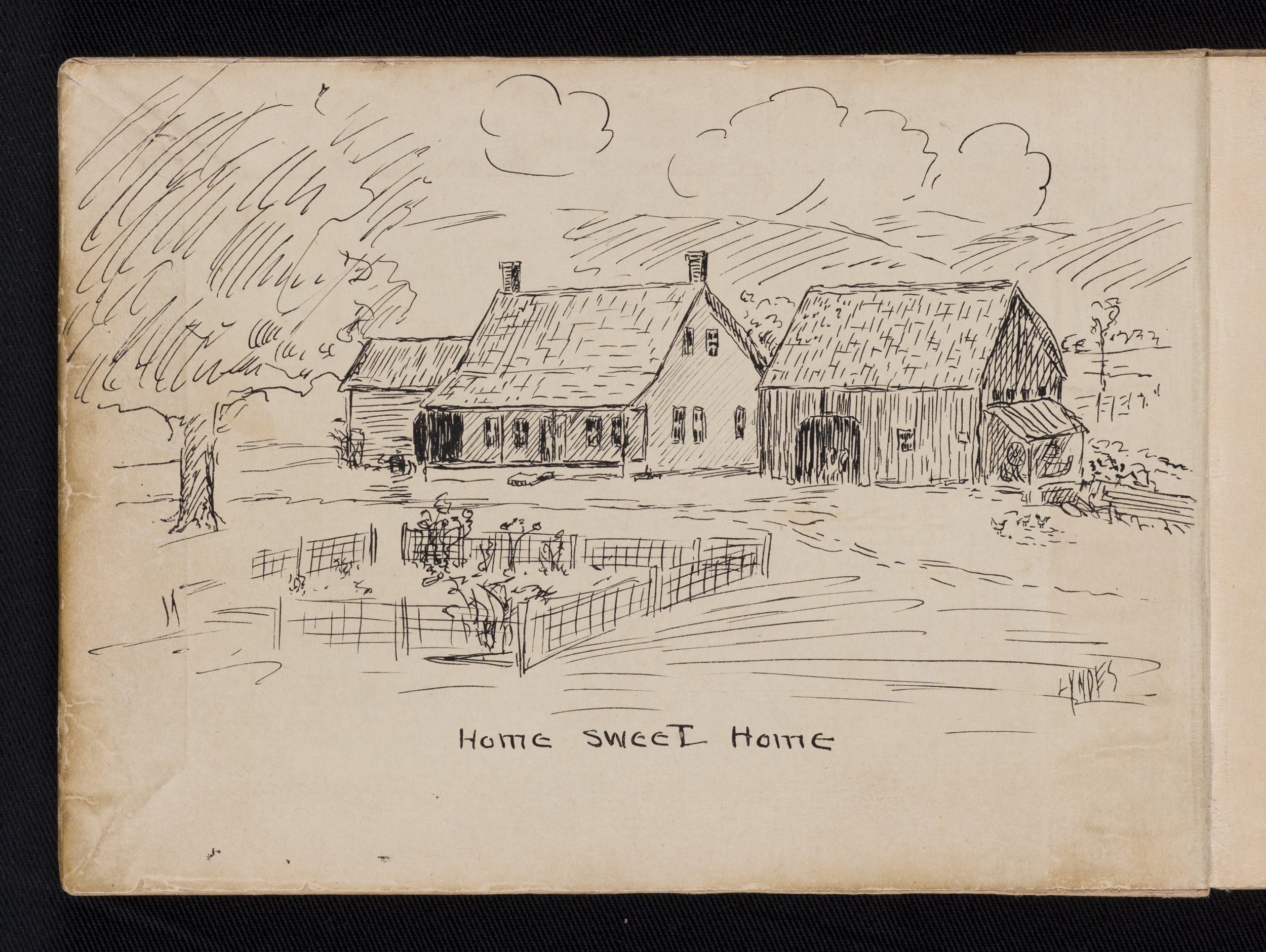

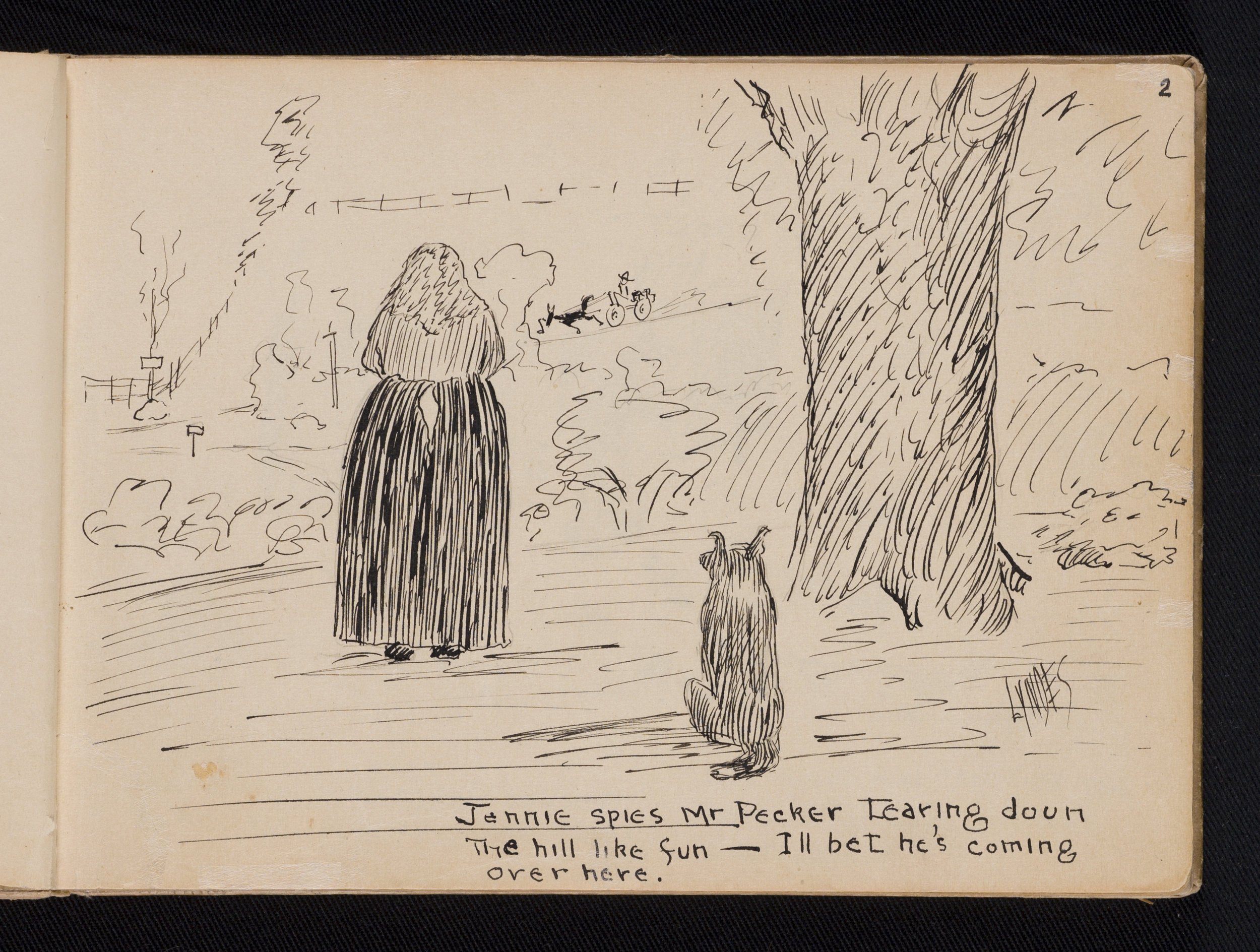

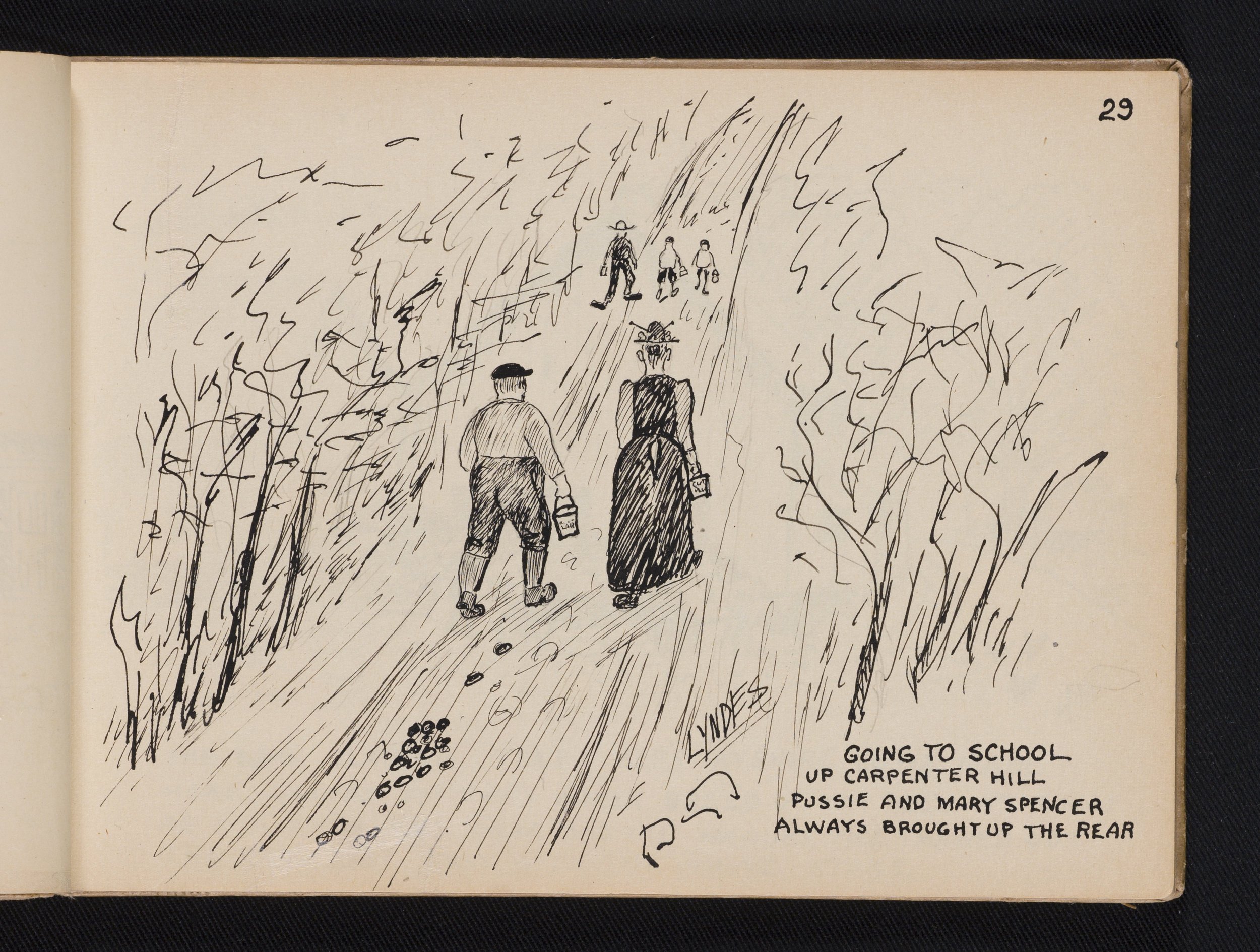

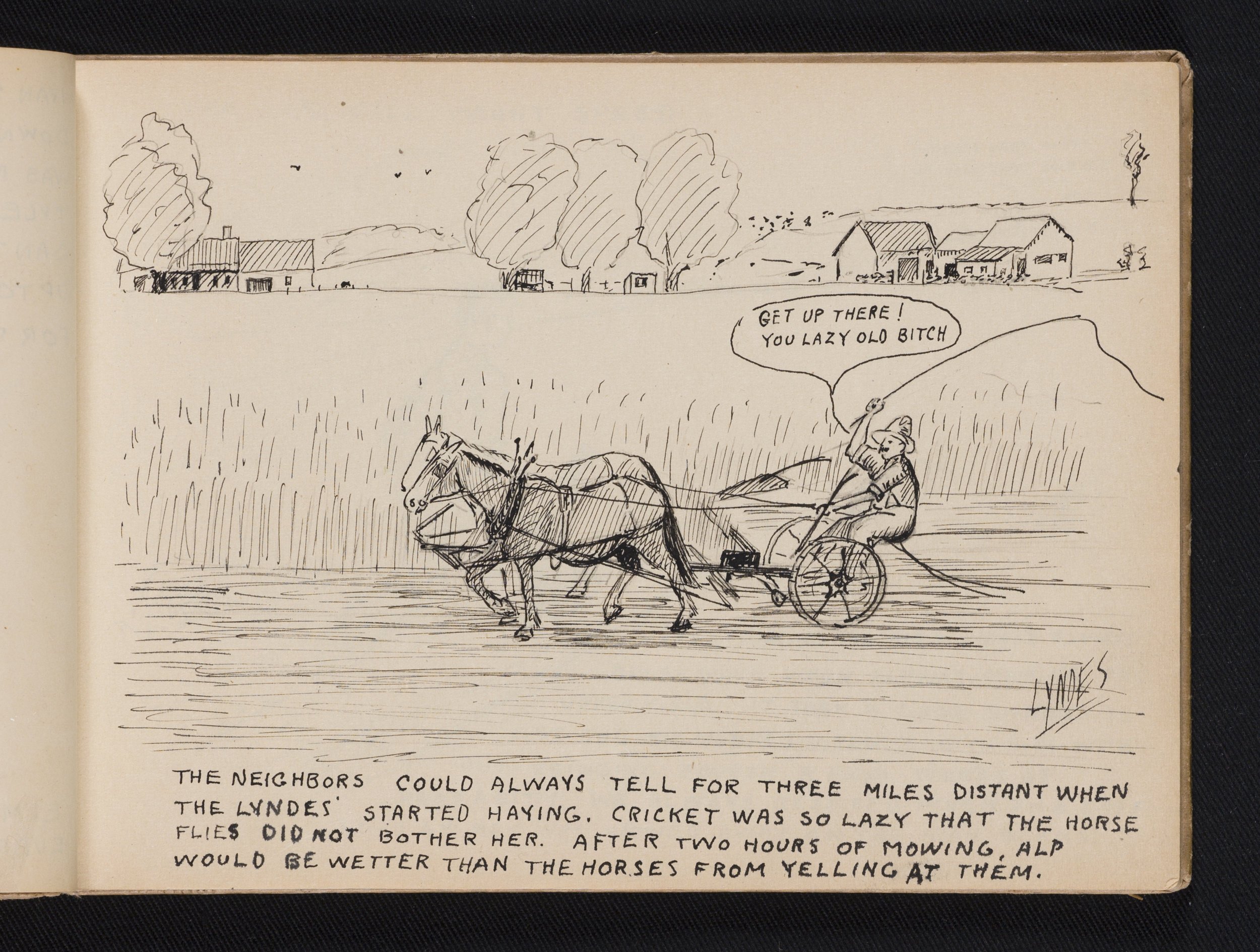

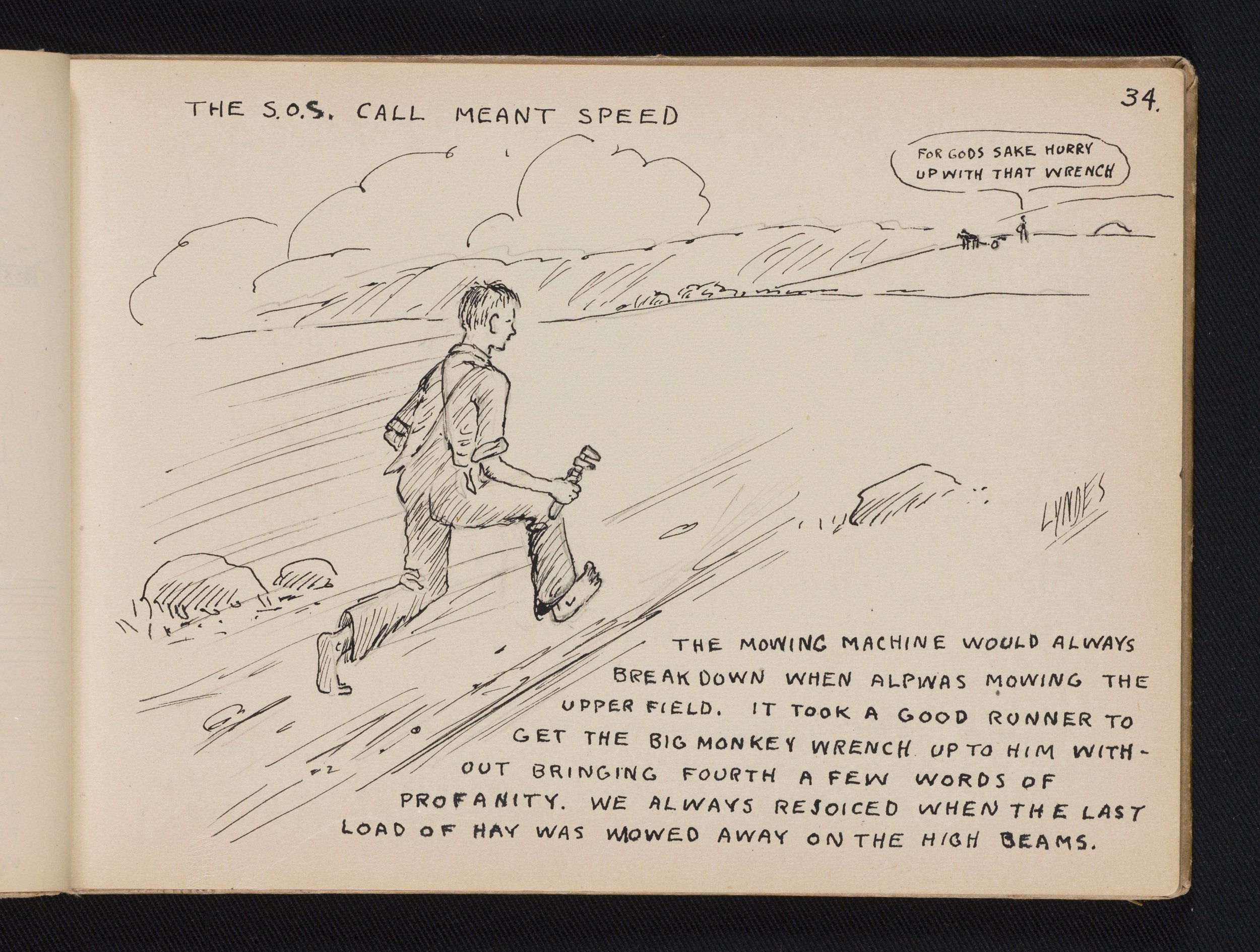

Stanley filled the book’s pages with the personalities and special facets of his family. In his pursuit, Stanley also represented elements common to rural life in Vermont and other places in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Hard work, the monotony of chores, and responsibilities shared by grandparents, parents, and children alike underlay all other activity.

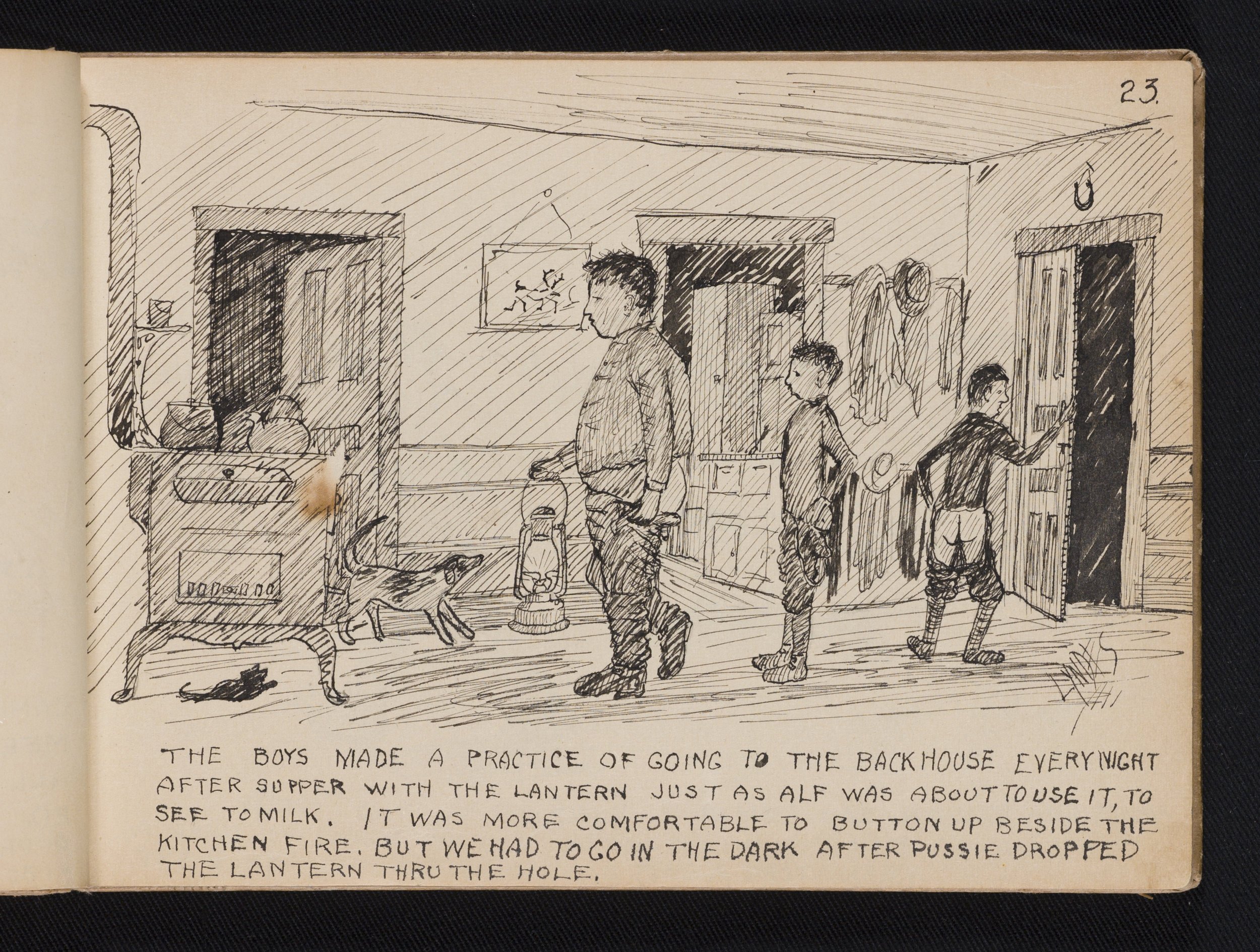

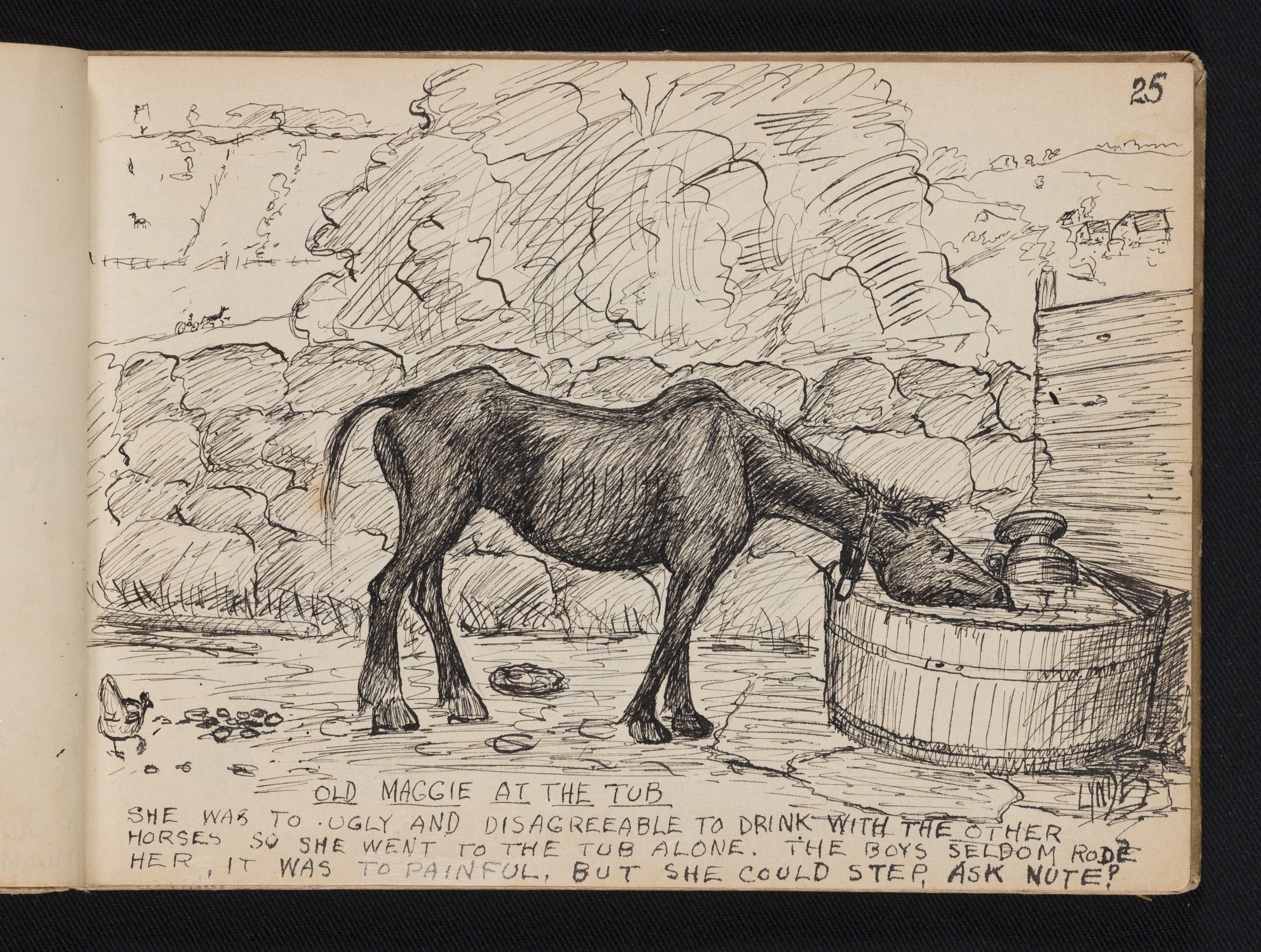

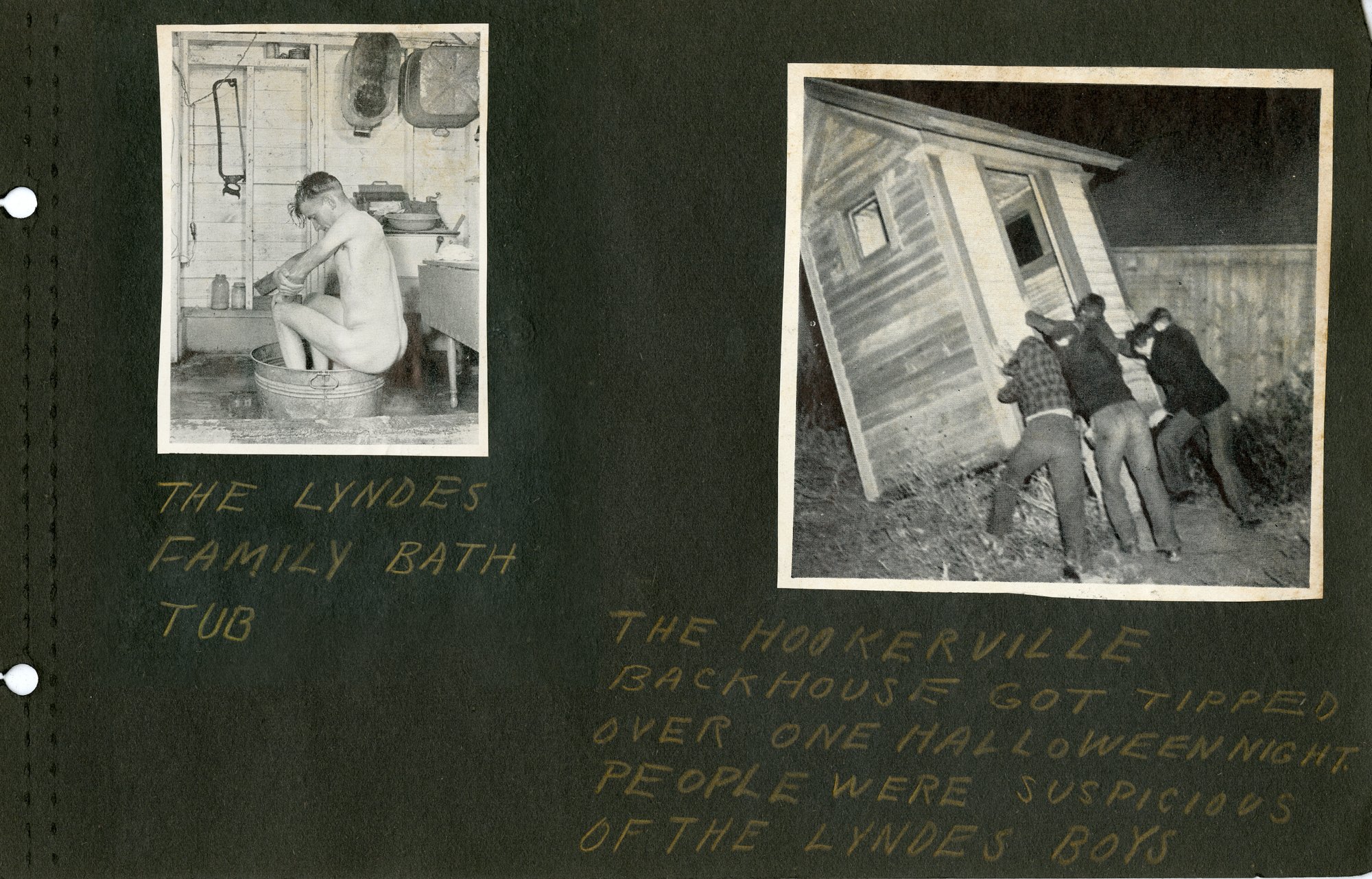

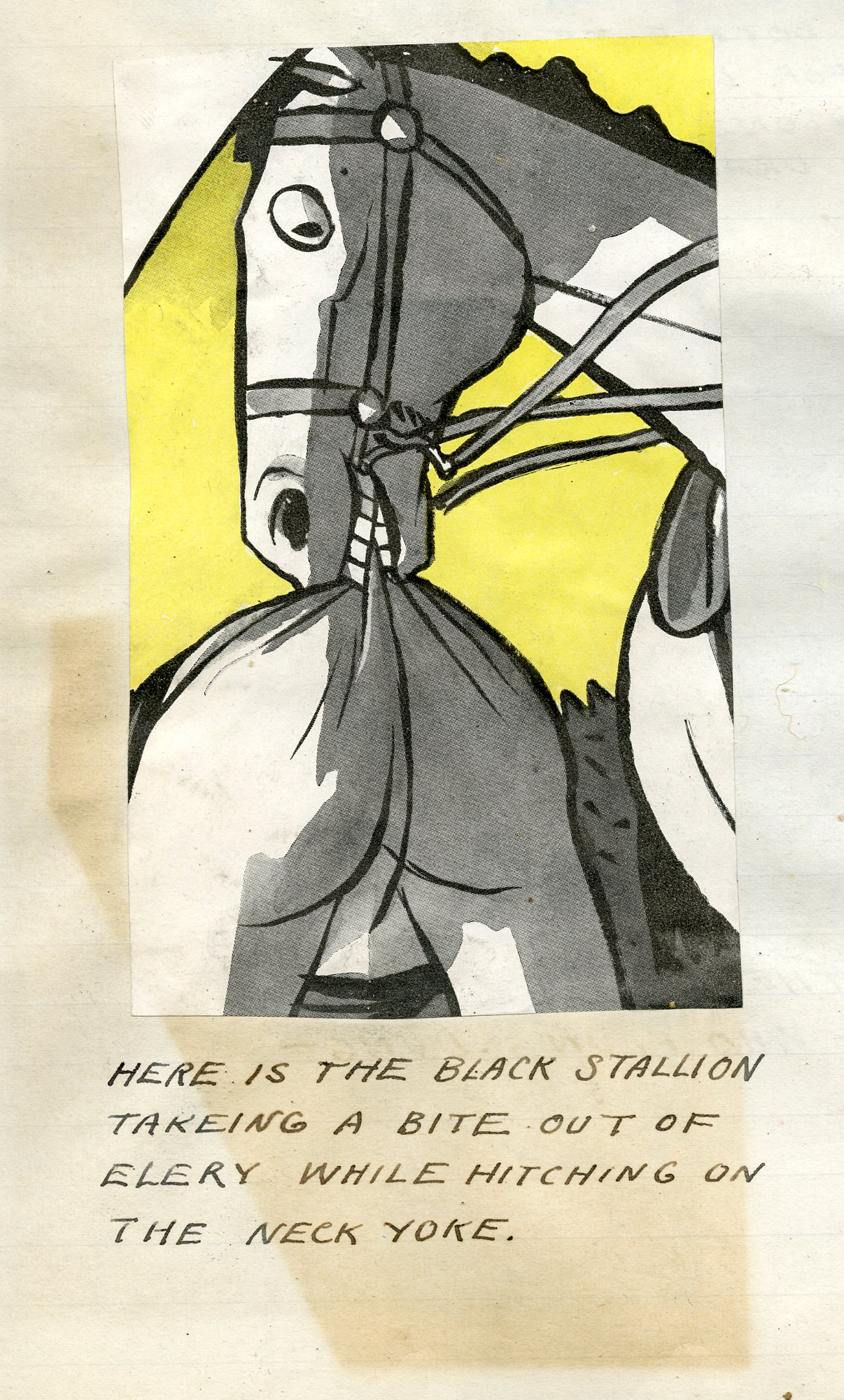

Rural families, such as the Lyndes, had little to spare and knew how to “make do” as the sketches revealed with their stress on the importance of pennies, homespun recreation, “Maggie”, the family horse, or small details as patches on a dress or pair of pants, the lunch pails made from lard buckets, the uses for skunk oil, and the inevitable “hand-me-downs.”

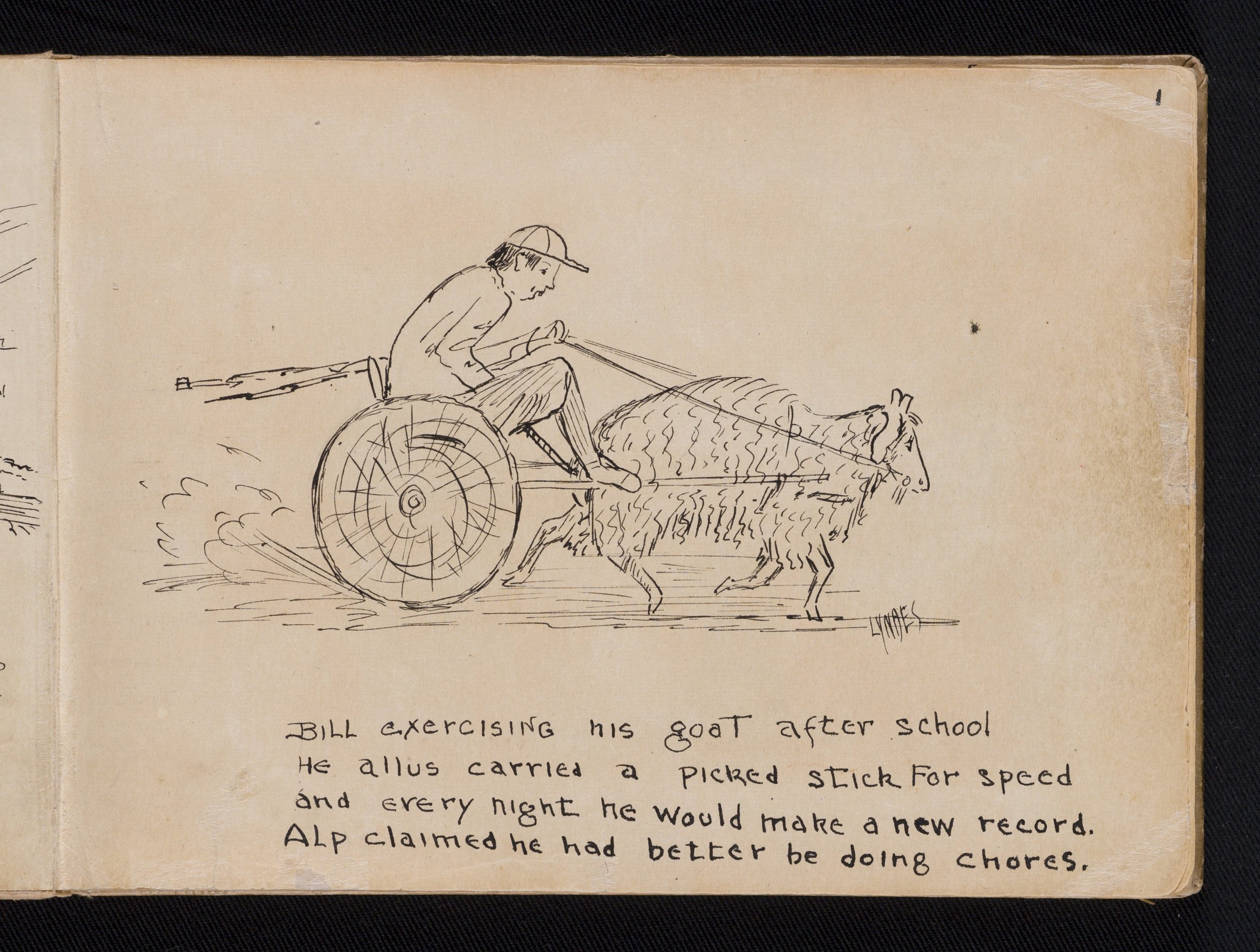

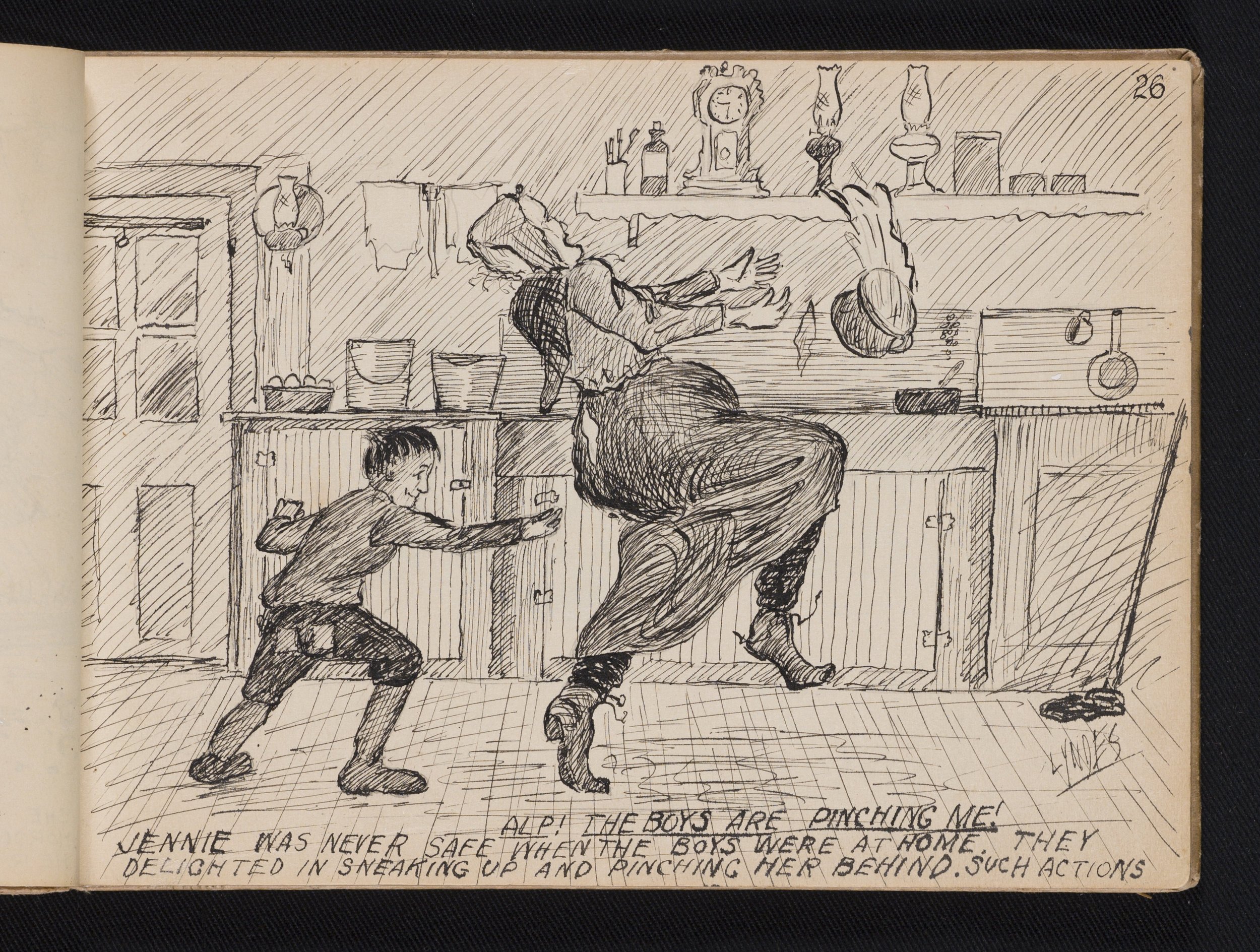

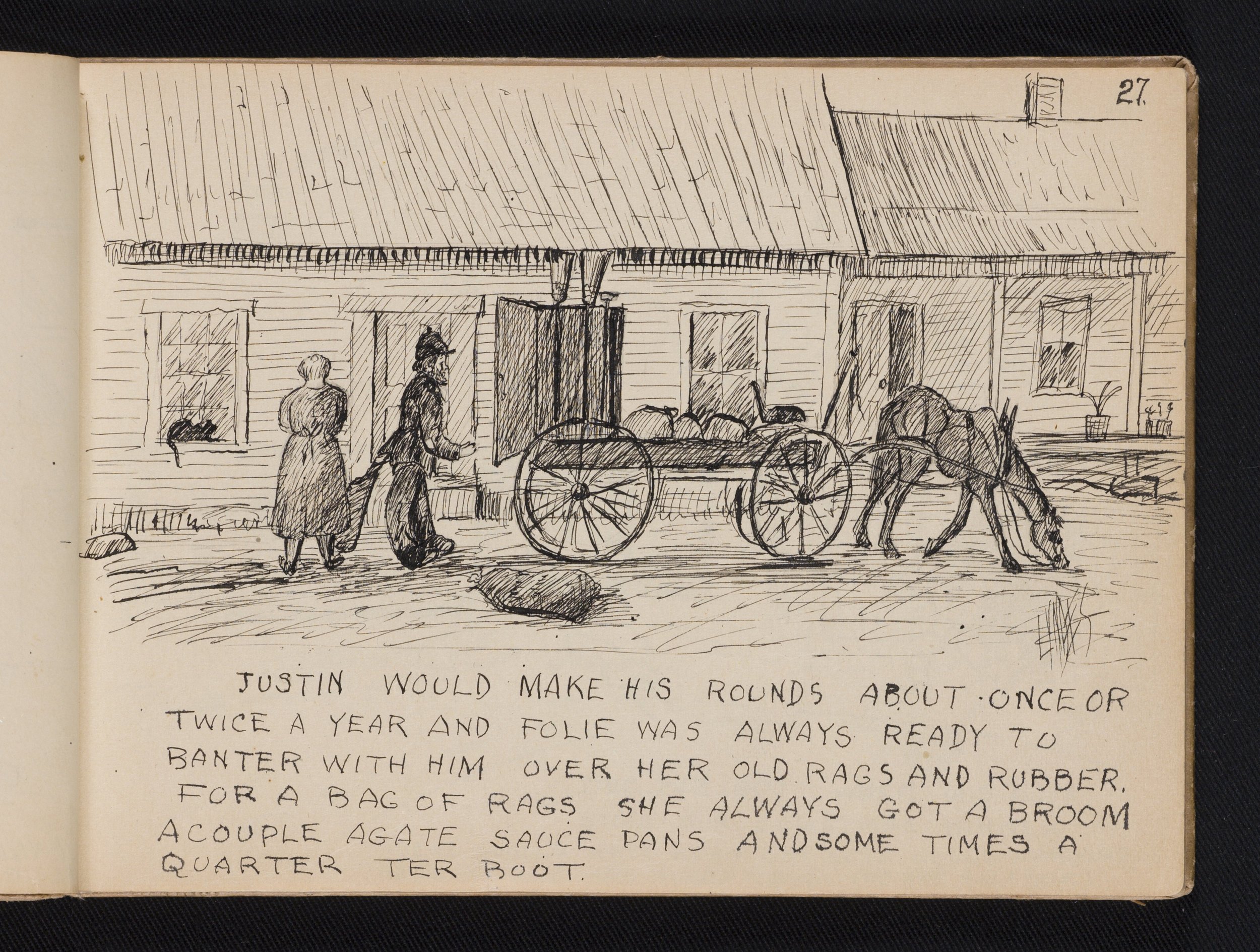

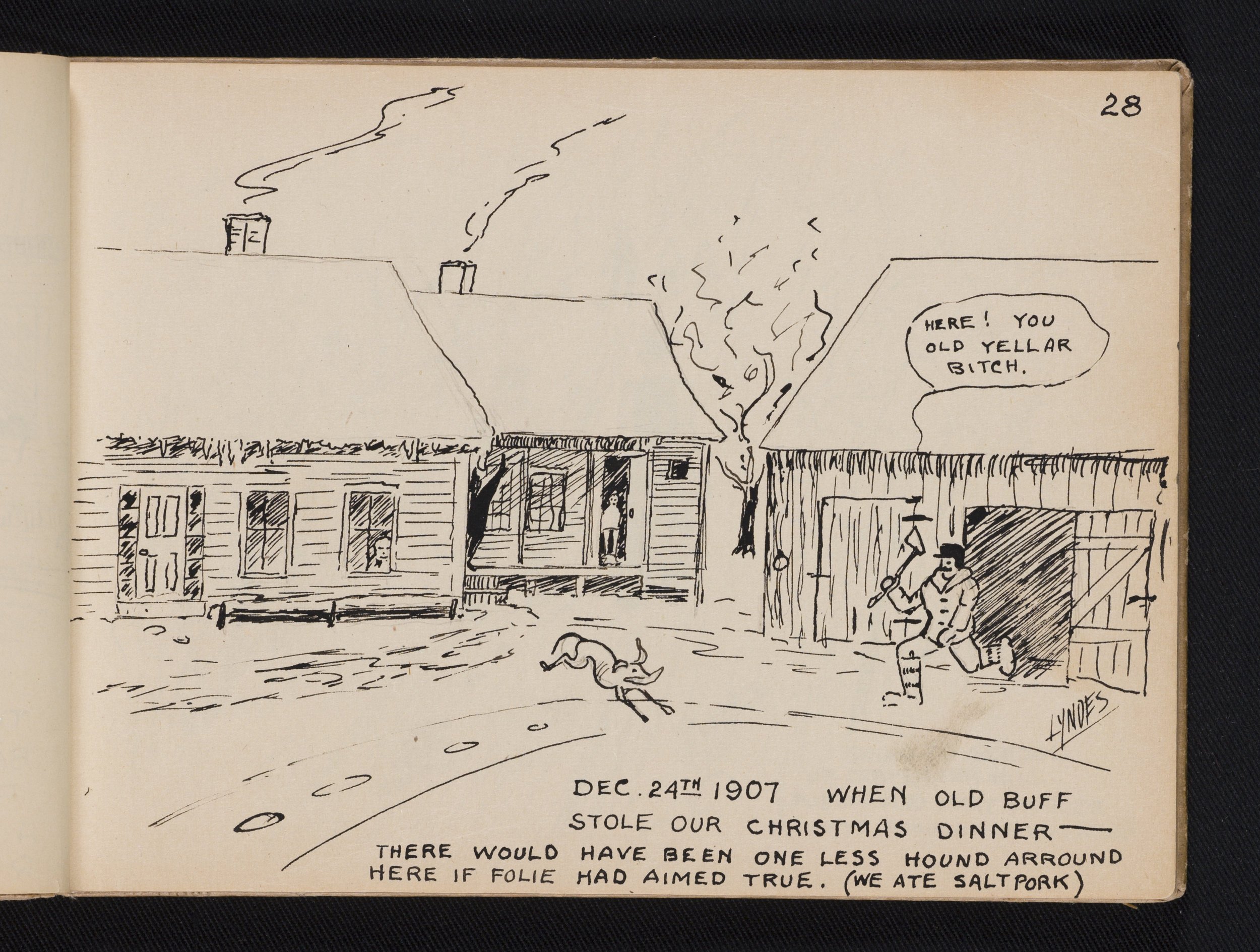

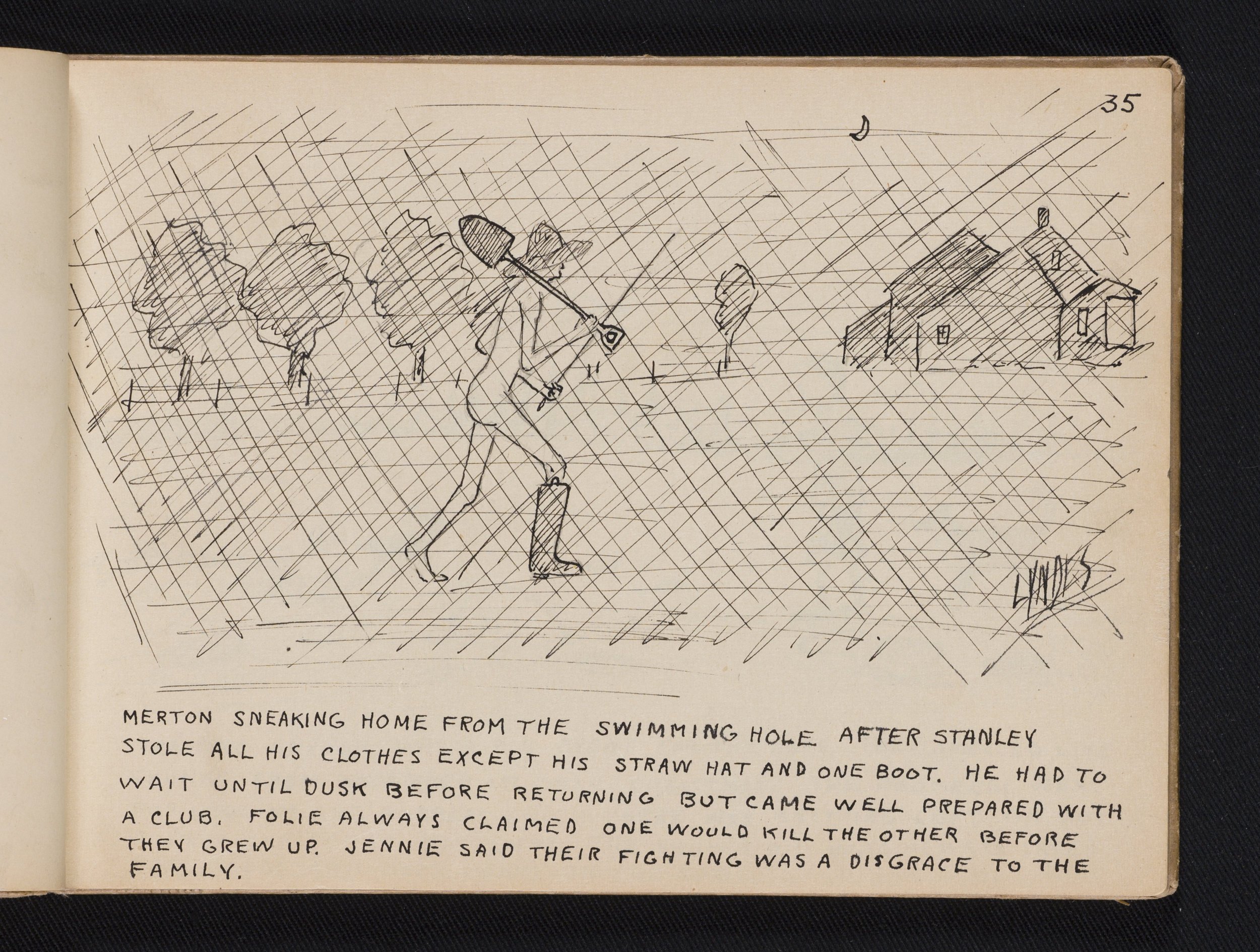

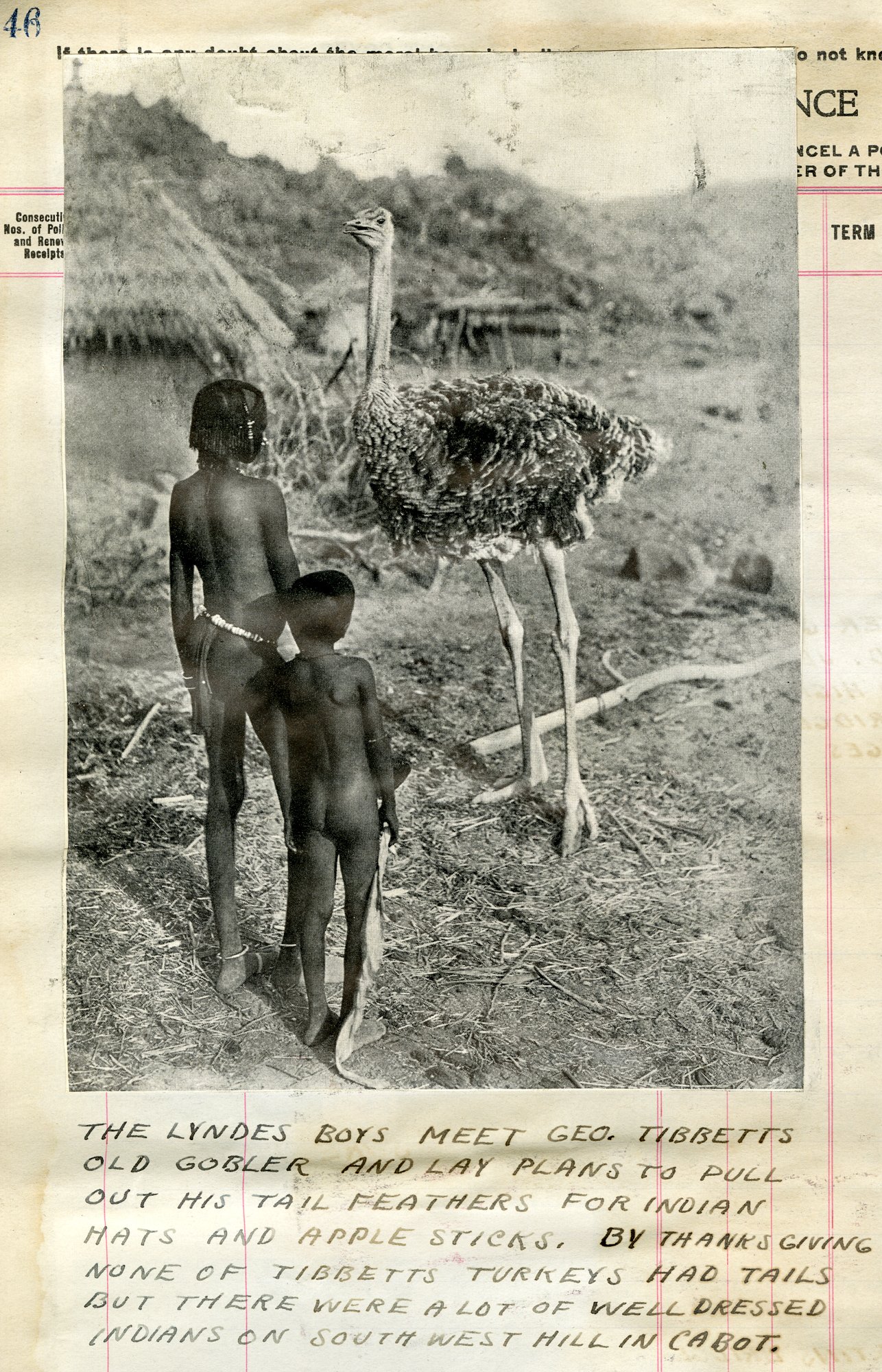

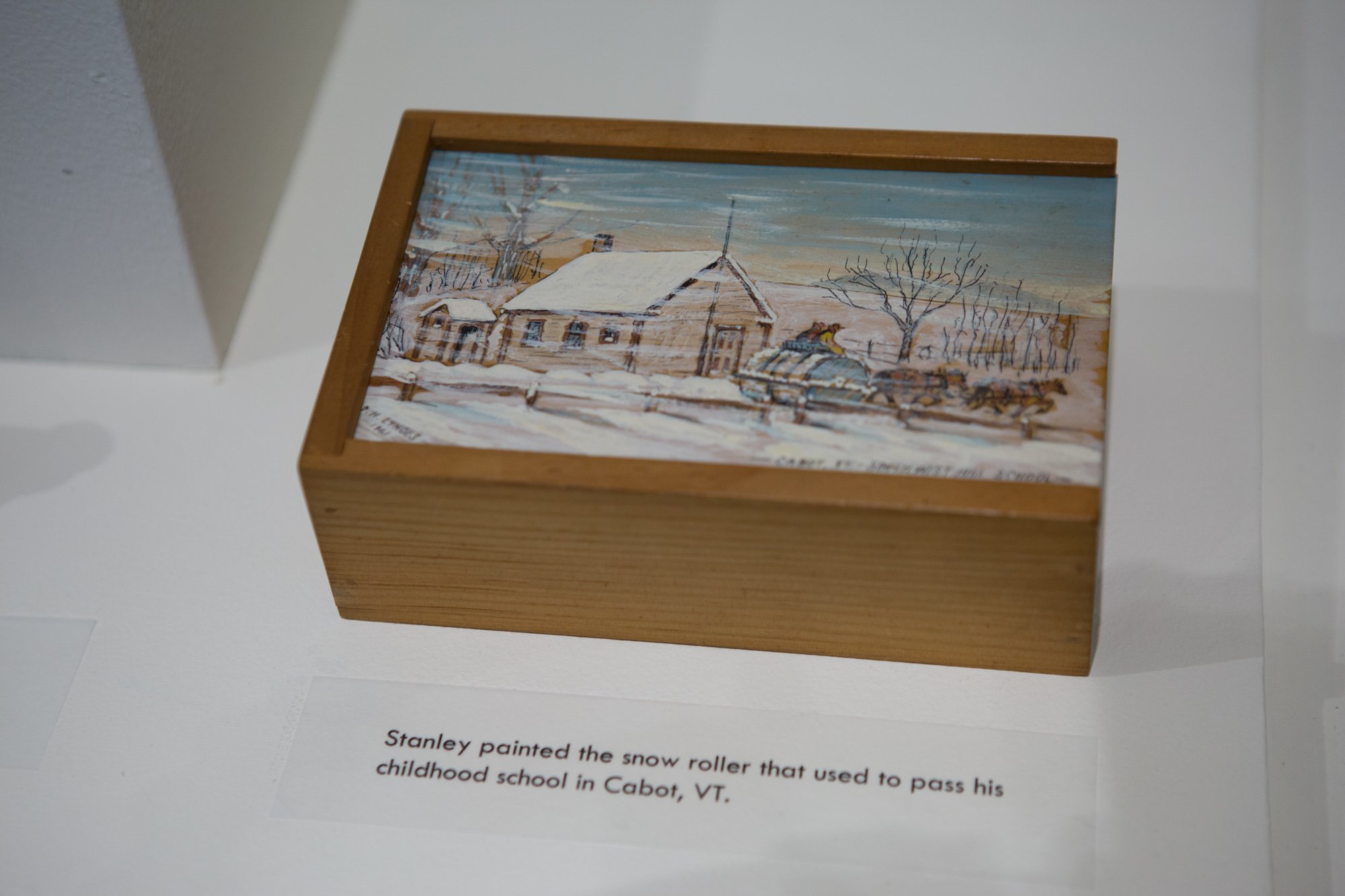

With a certain boyish rascality his sketches recall the swimming hole, the fascination with racing and speed, the lively pranks, and the earthy humor. The family, with three generations living under the same roof, showed patience and love. The family also witnessed moments of anger, and the practical jokes often had a faintly cruel twist as they played on individual foibles. Yet the family generally lived happily together, working and entertaining themselves in the seasonal rhythm of the hill farm and looking forward to the ragman’s visit, sugaring-off, rolling the snow, or Christmas dinner to relieve the steady round of chores.

Hard living was not necessarily bad living, and the stern life on a Vermont farm and its “cold crude days,” as Lyndes called them, brought a certain warmth.

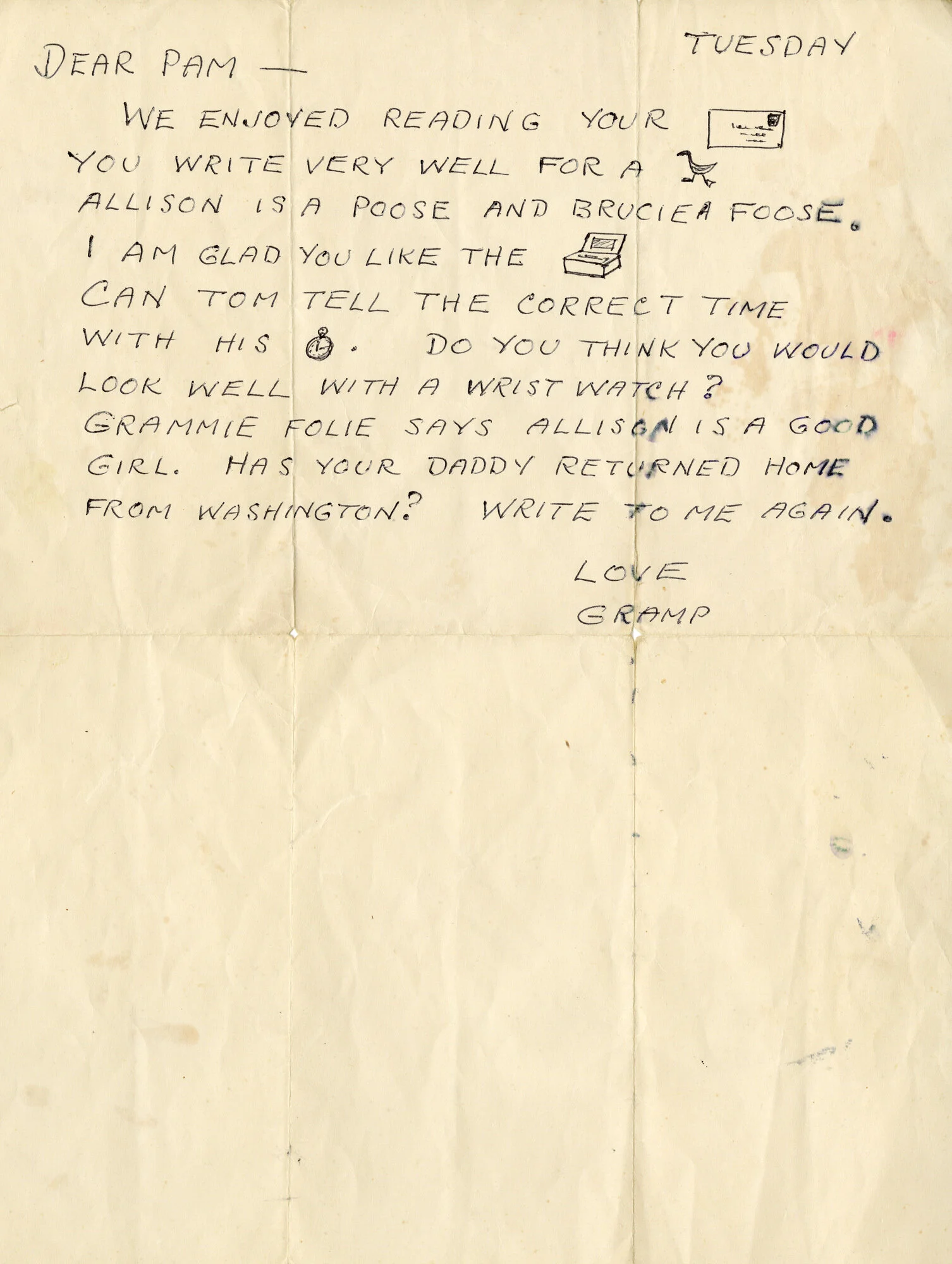

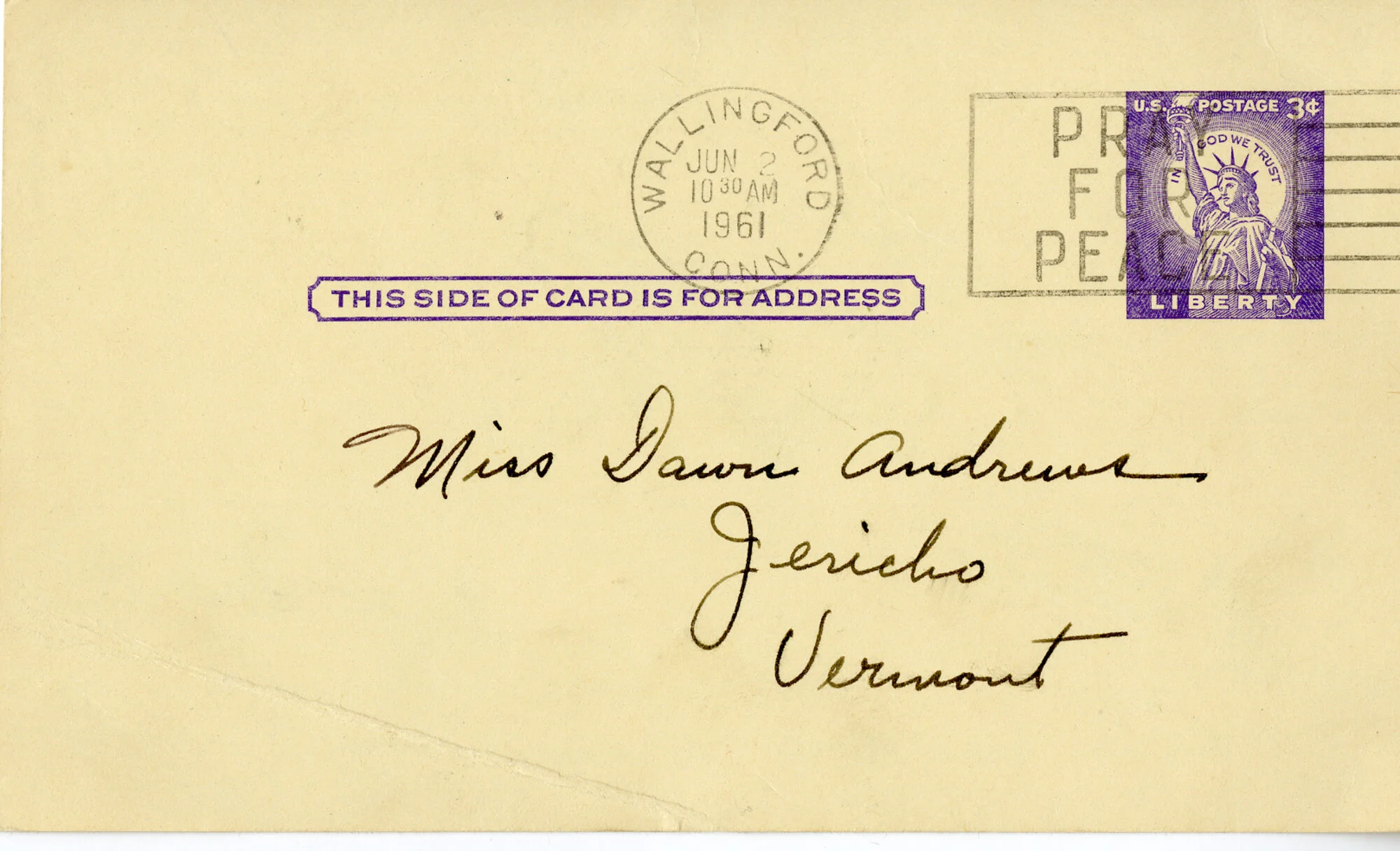

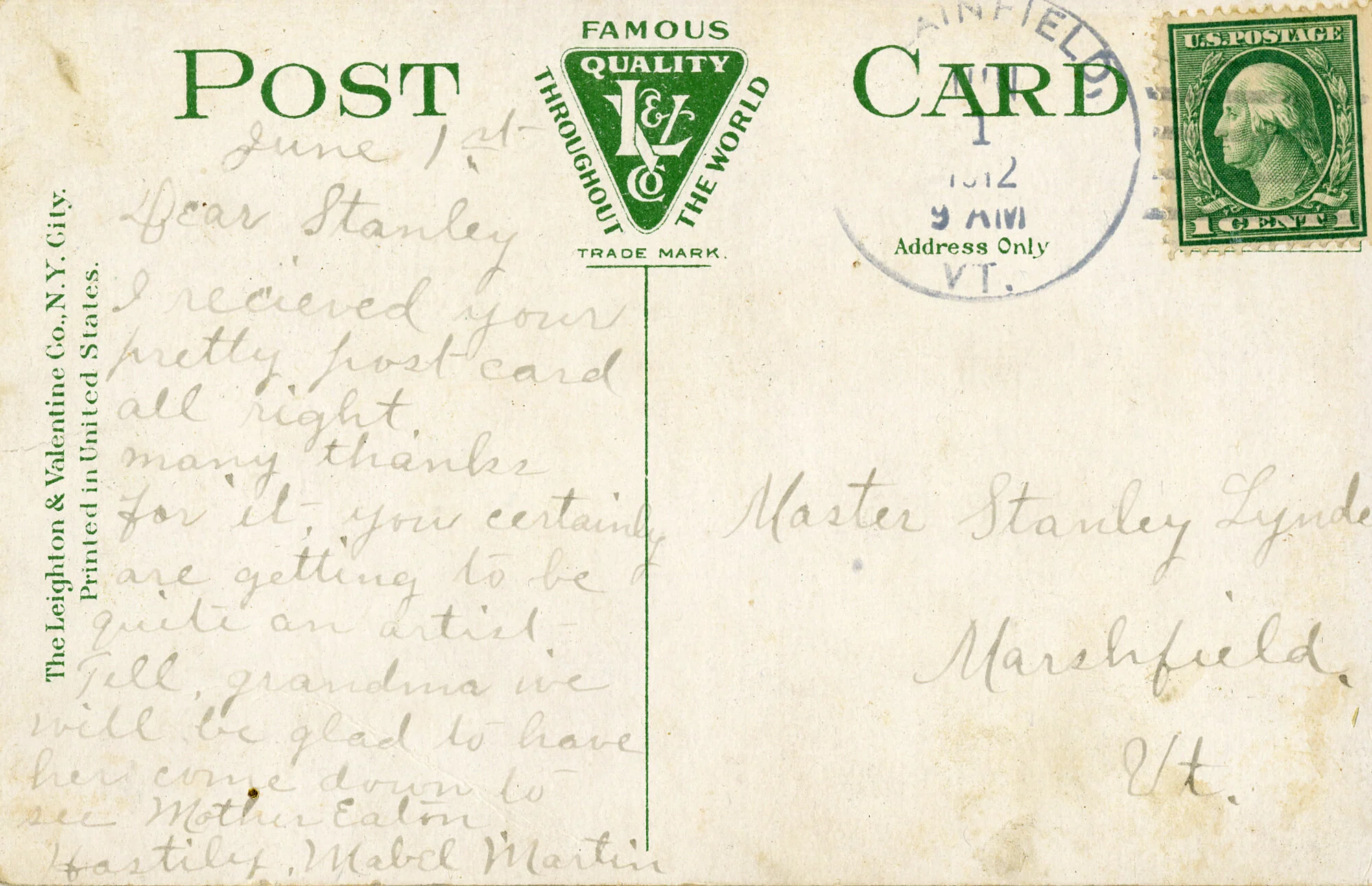

Letters

Gramp not only captured the vibrant familial culture of the Lyndes, he was also a builder of family connections.

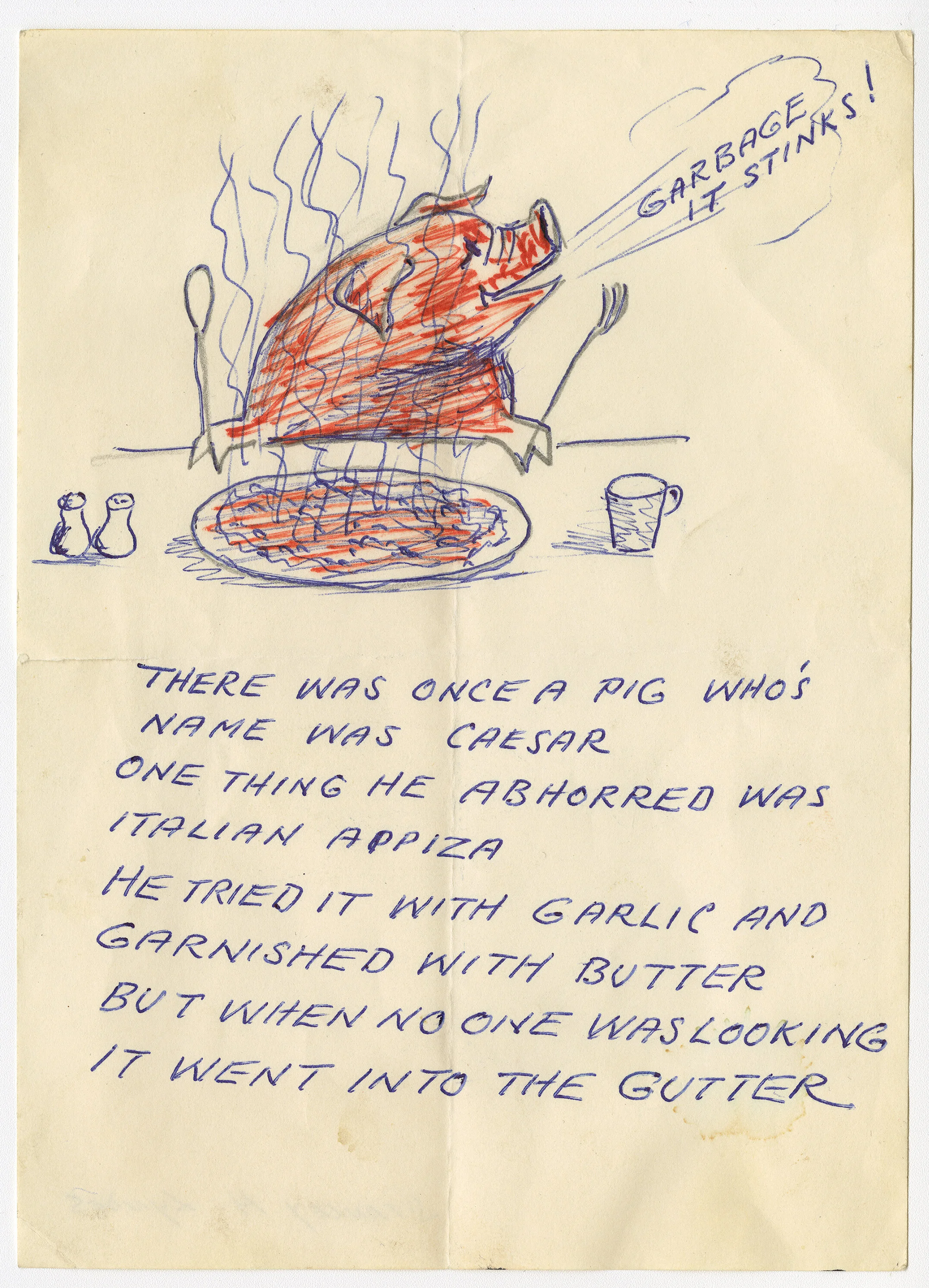

He made a point to keep in touch with his children and grandchildren through the mail—often sending hand drawn birthday cards, a comic strip, or a postcard.

Mail from Gramp might be triggered by a meaningful date or event, and sometimes it was unprompted—an expression of a loving Gramp once again living out his creativity within the context of family life.

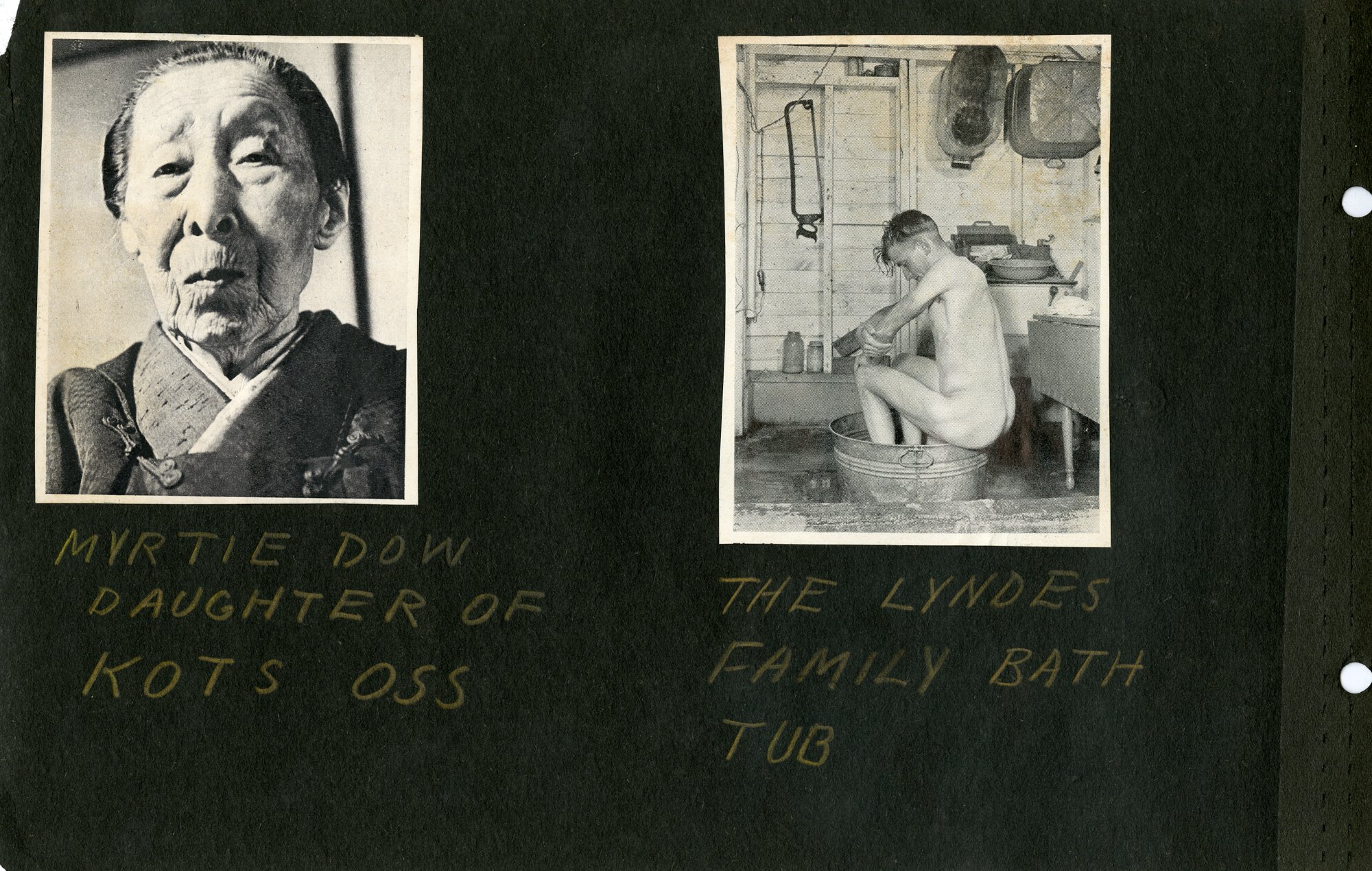

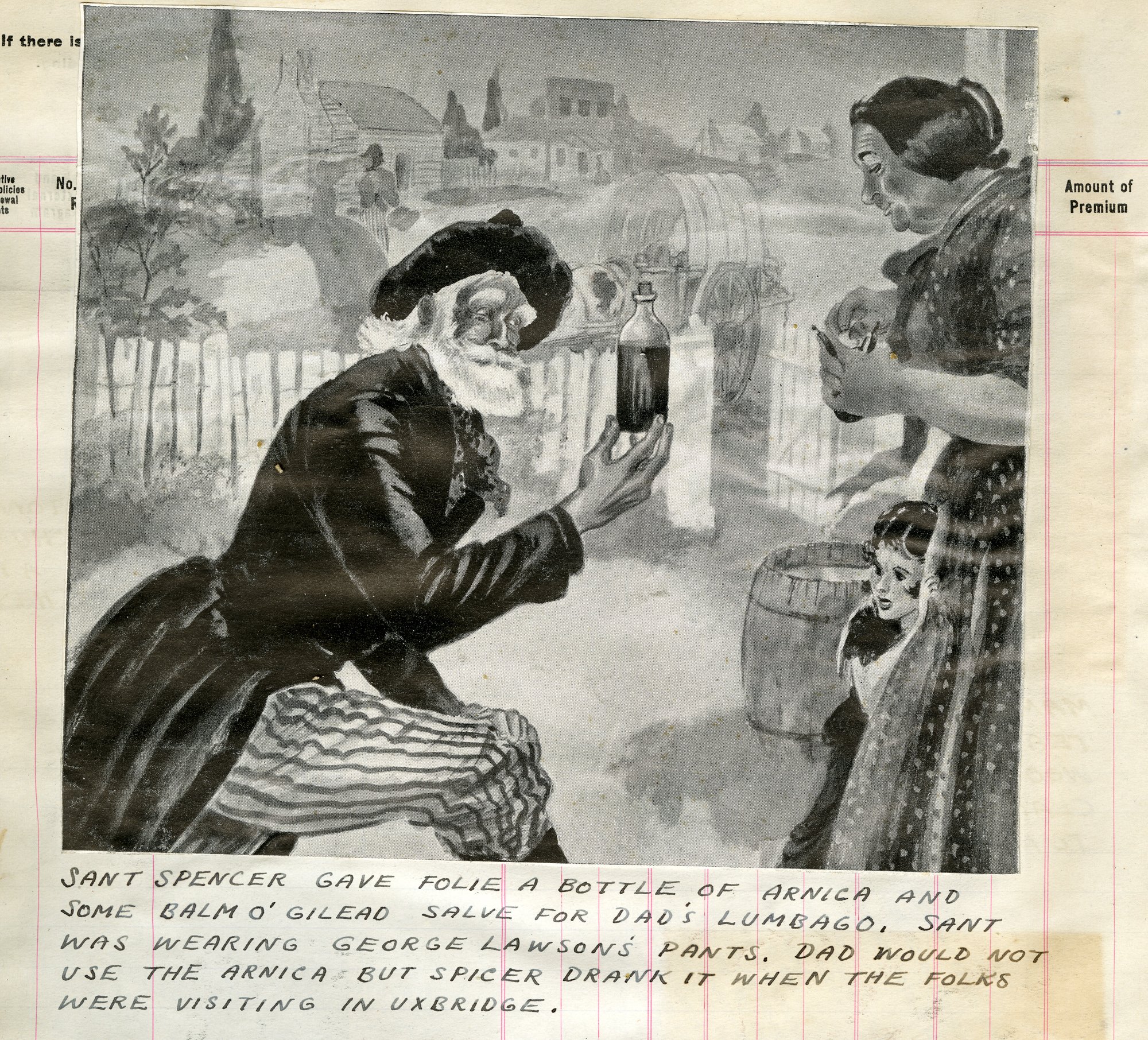

Scrapbooks

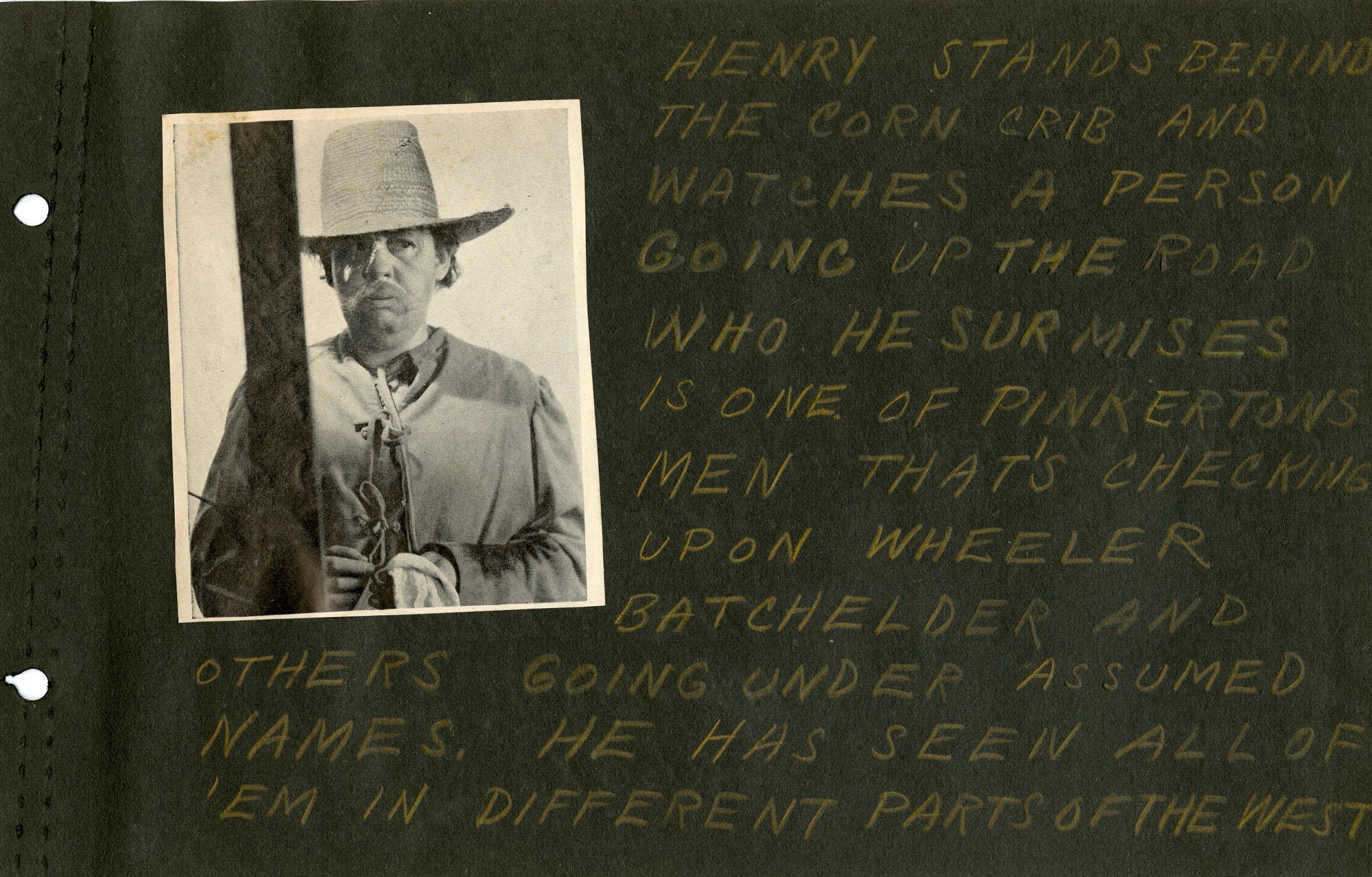

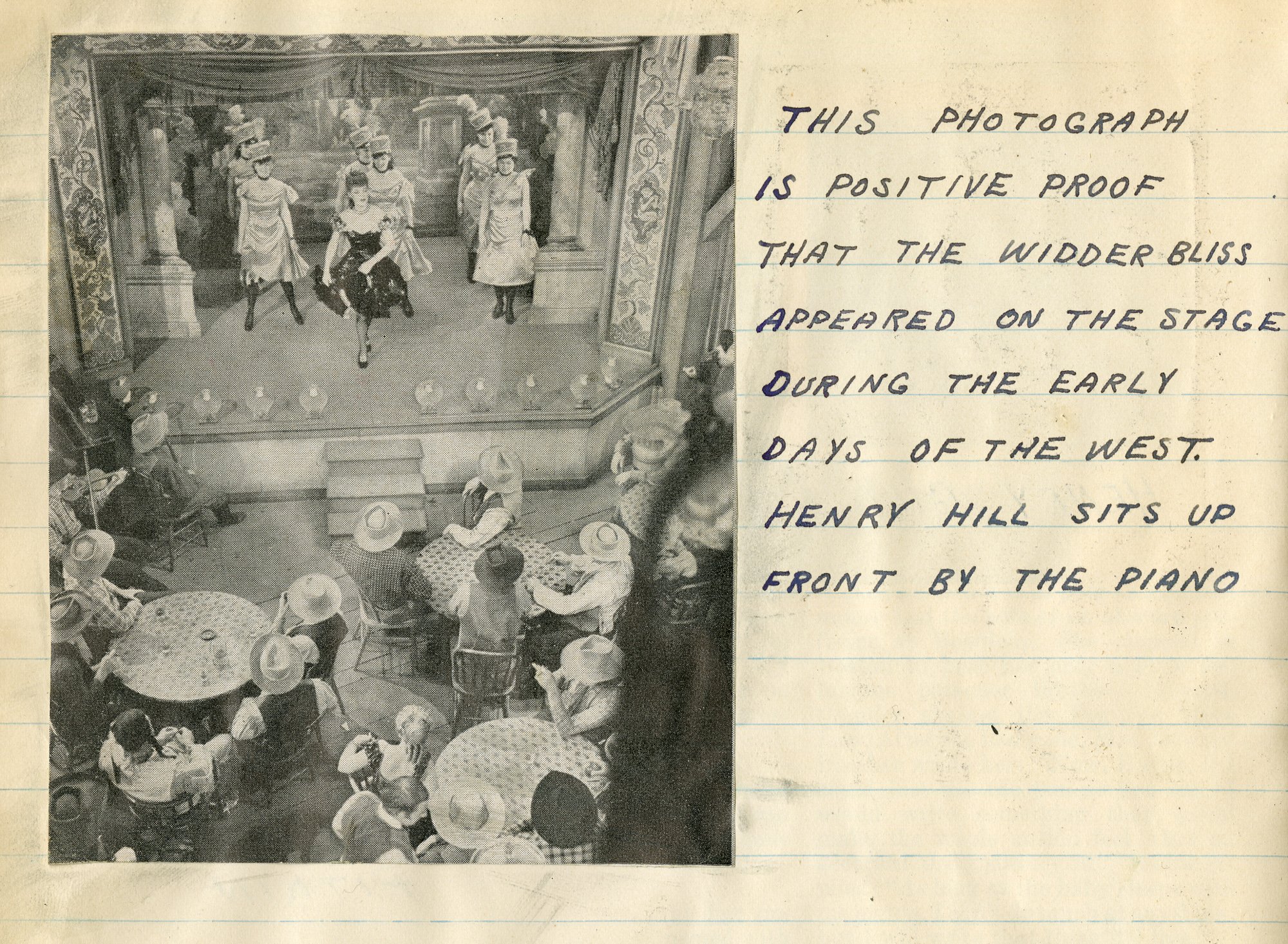

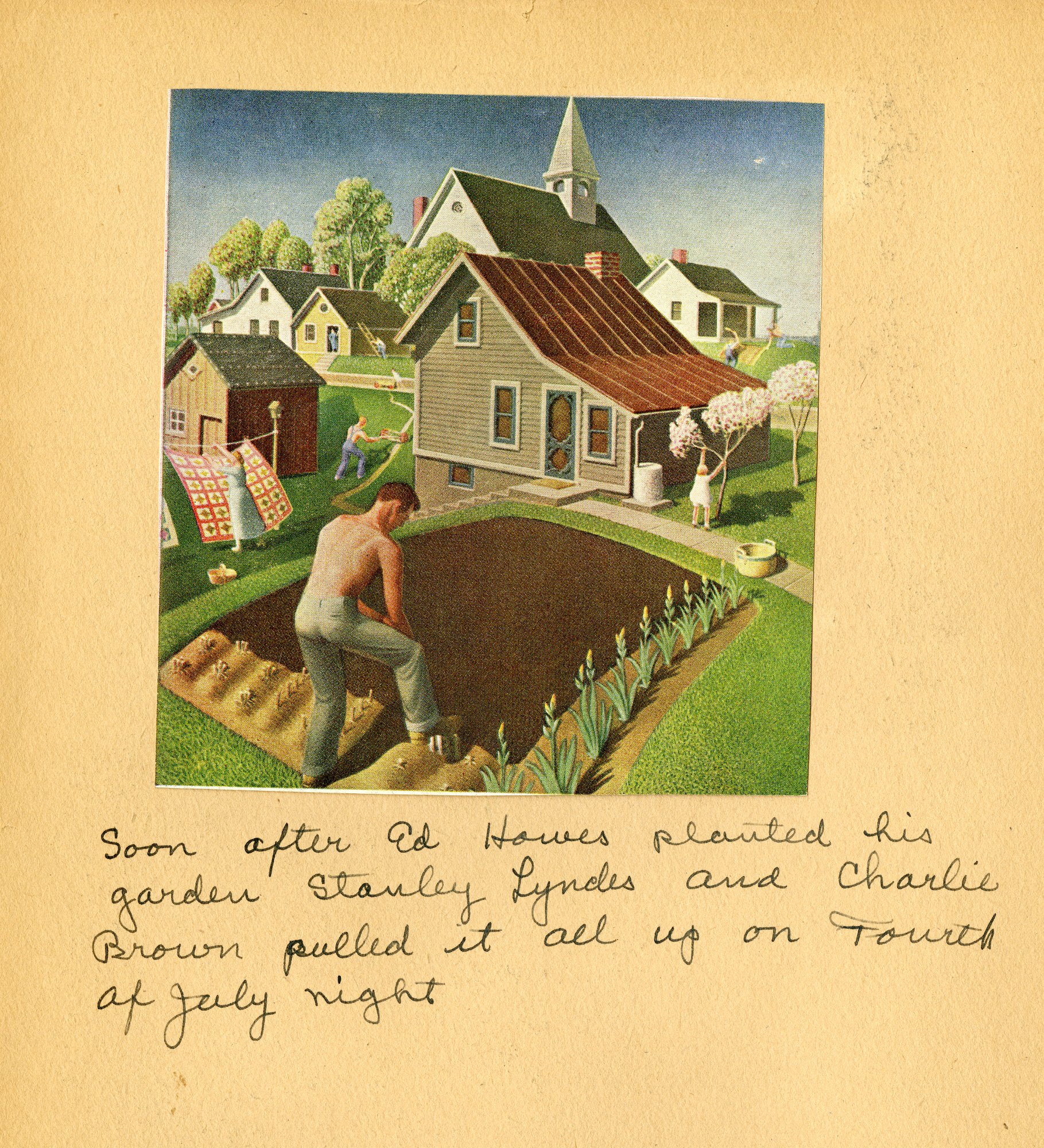

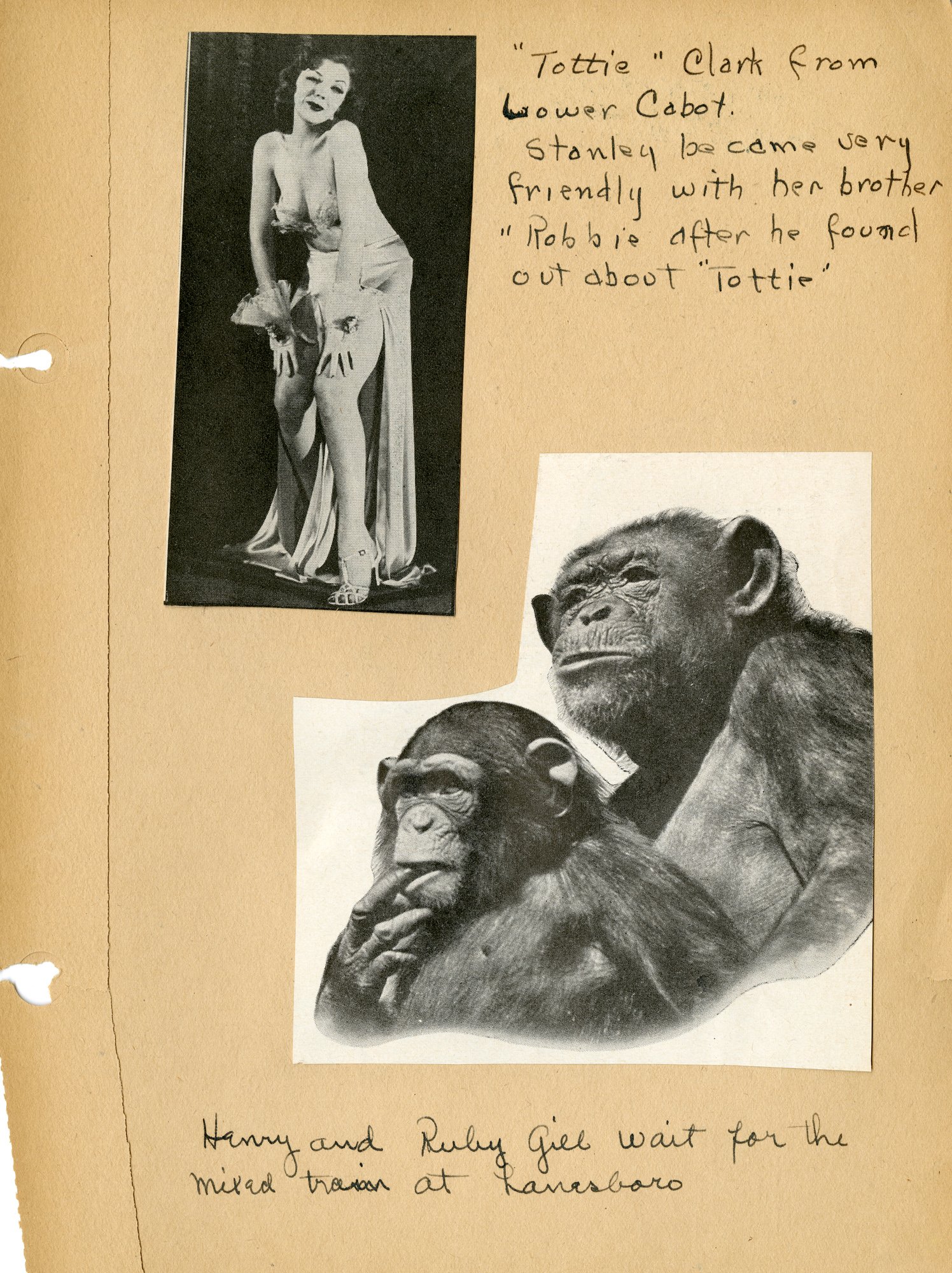

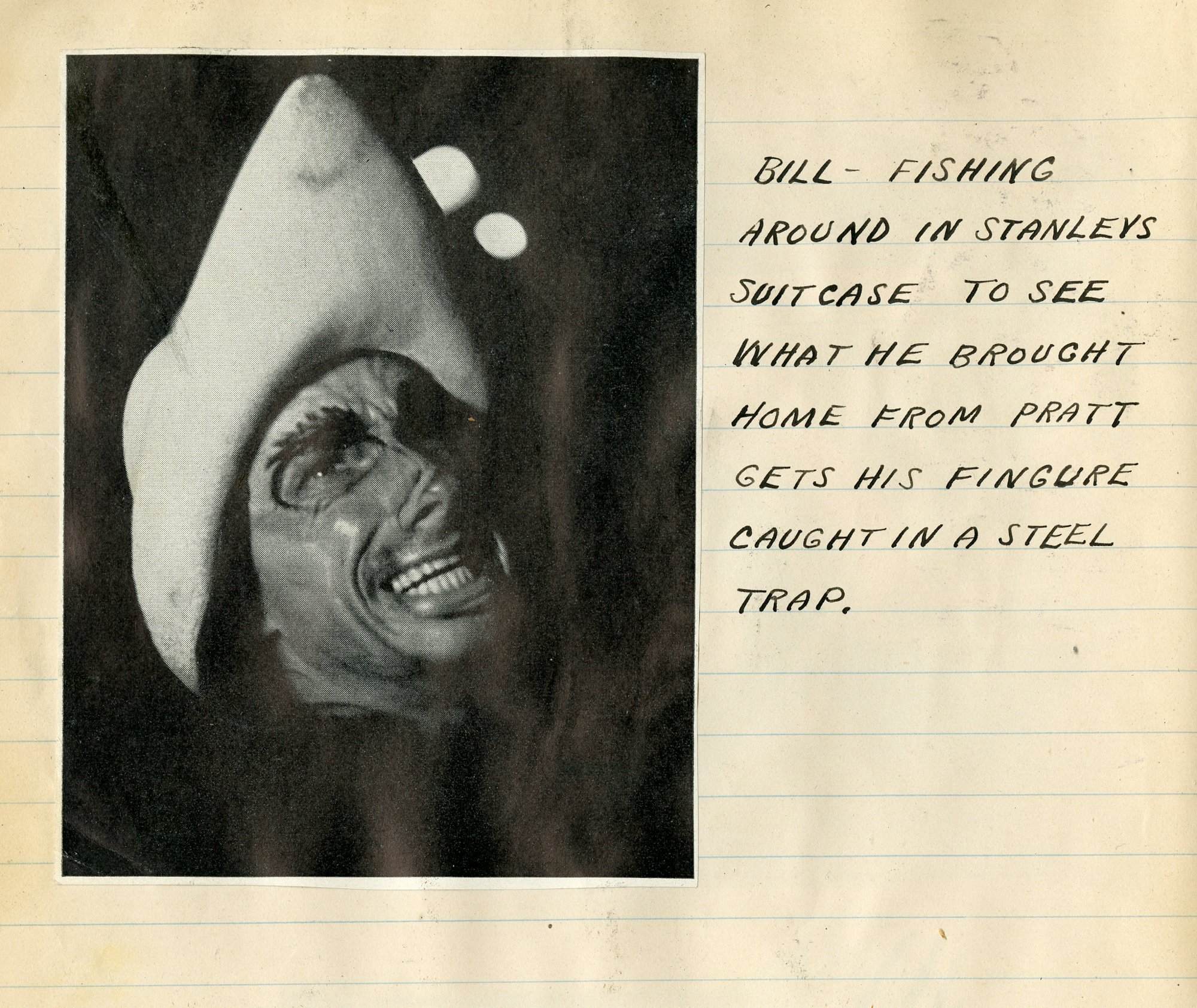

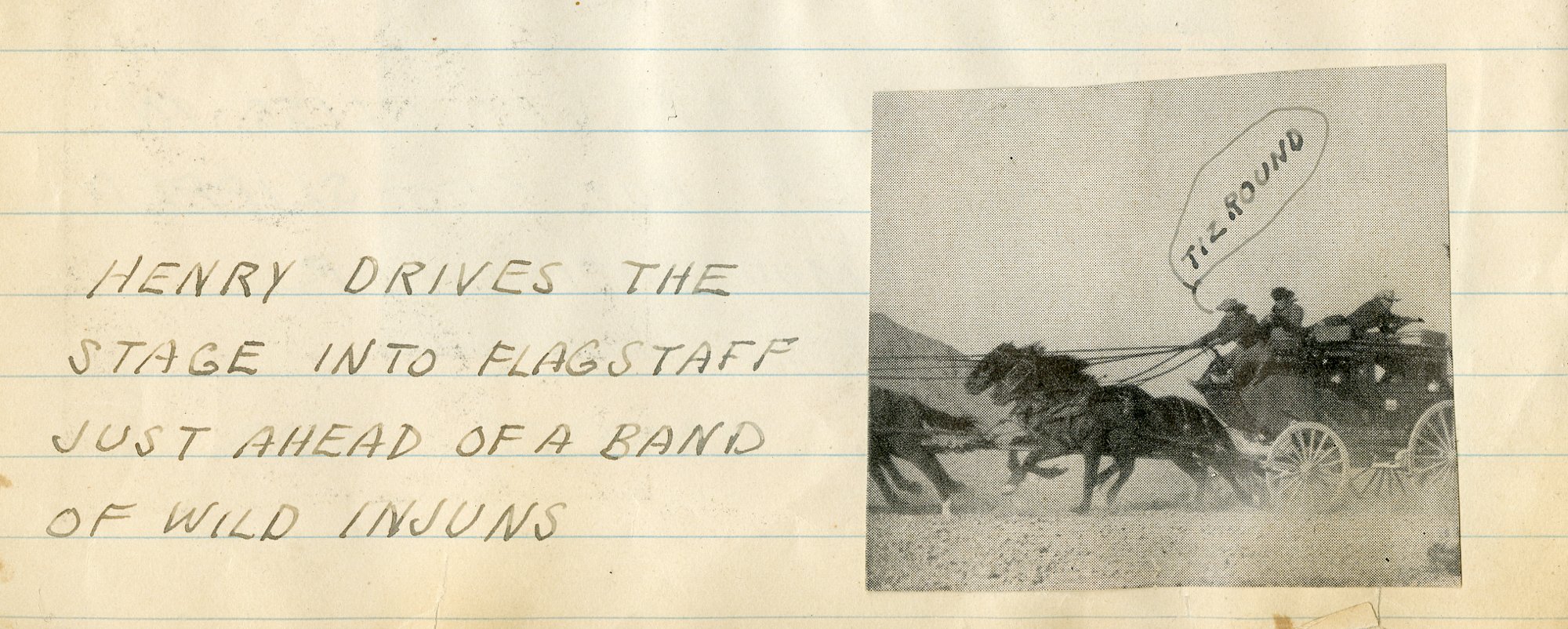

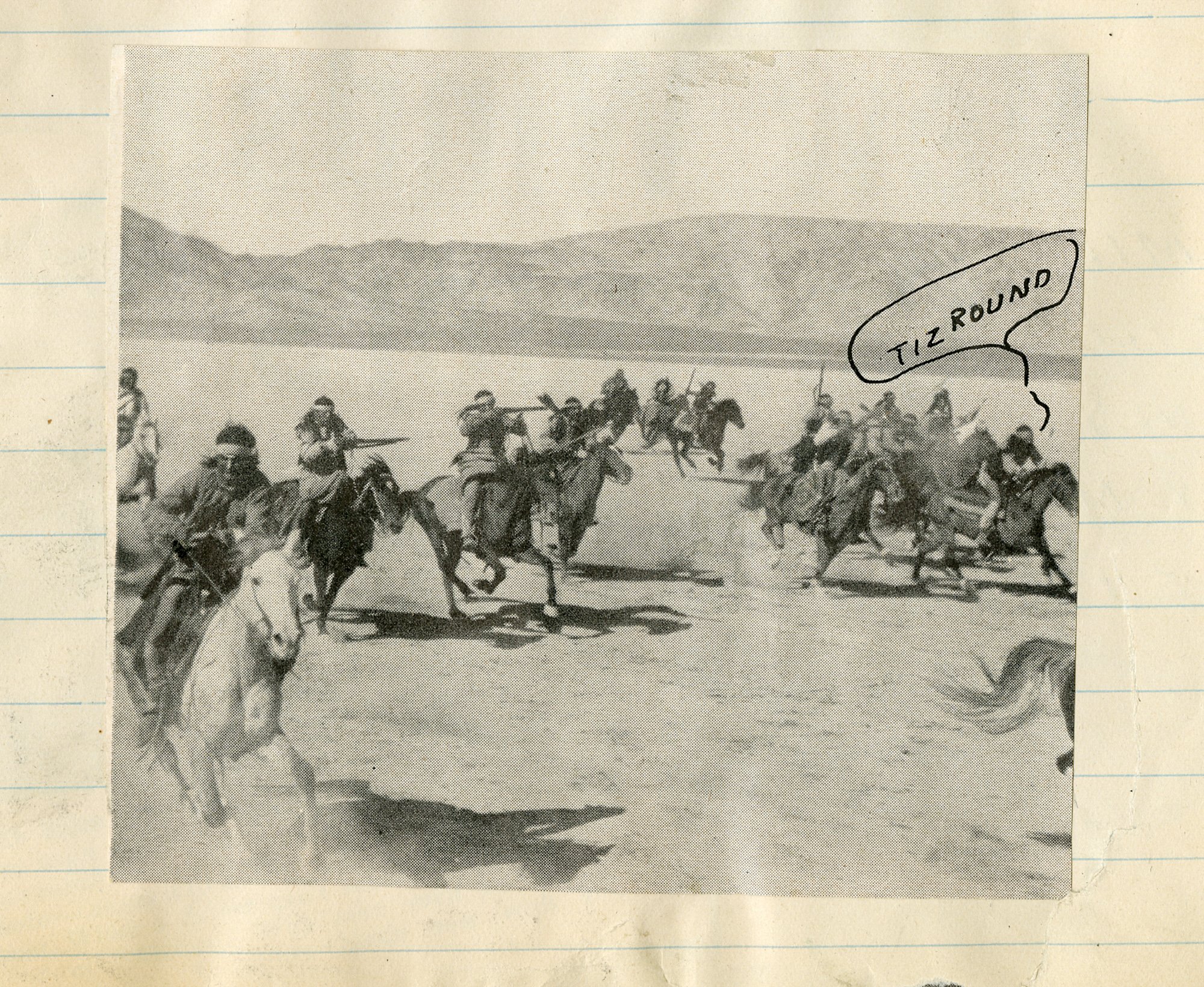

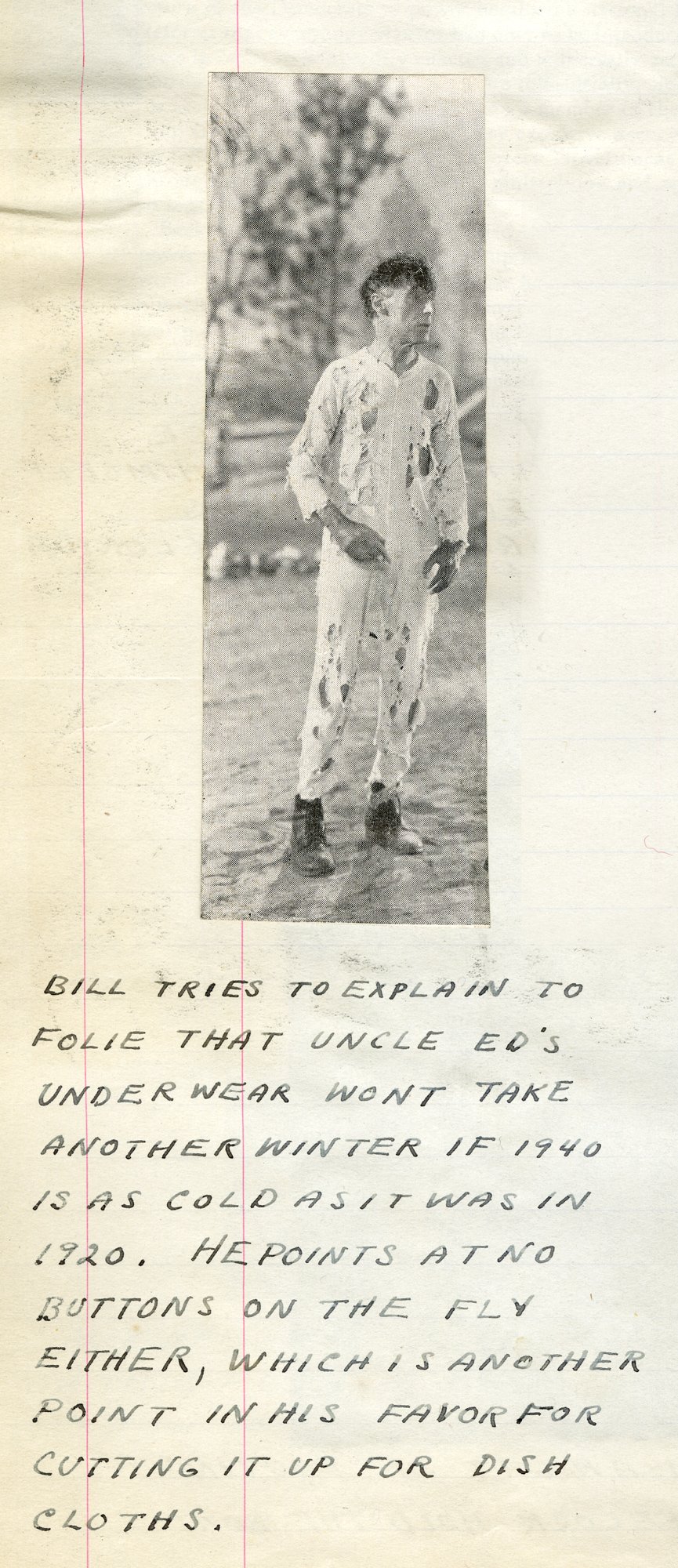

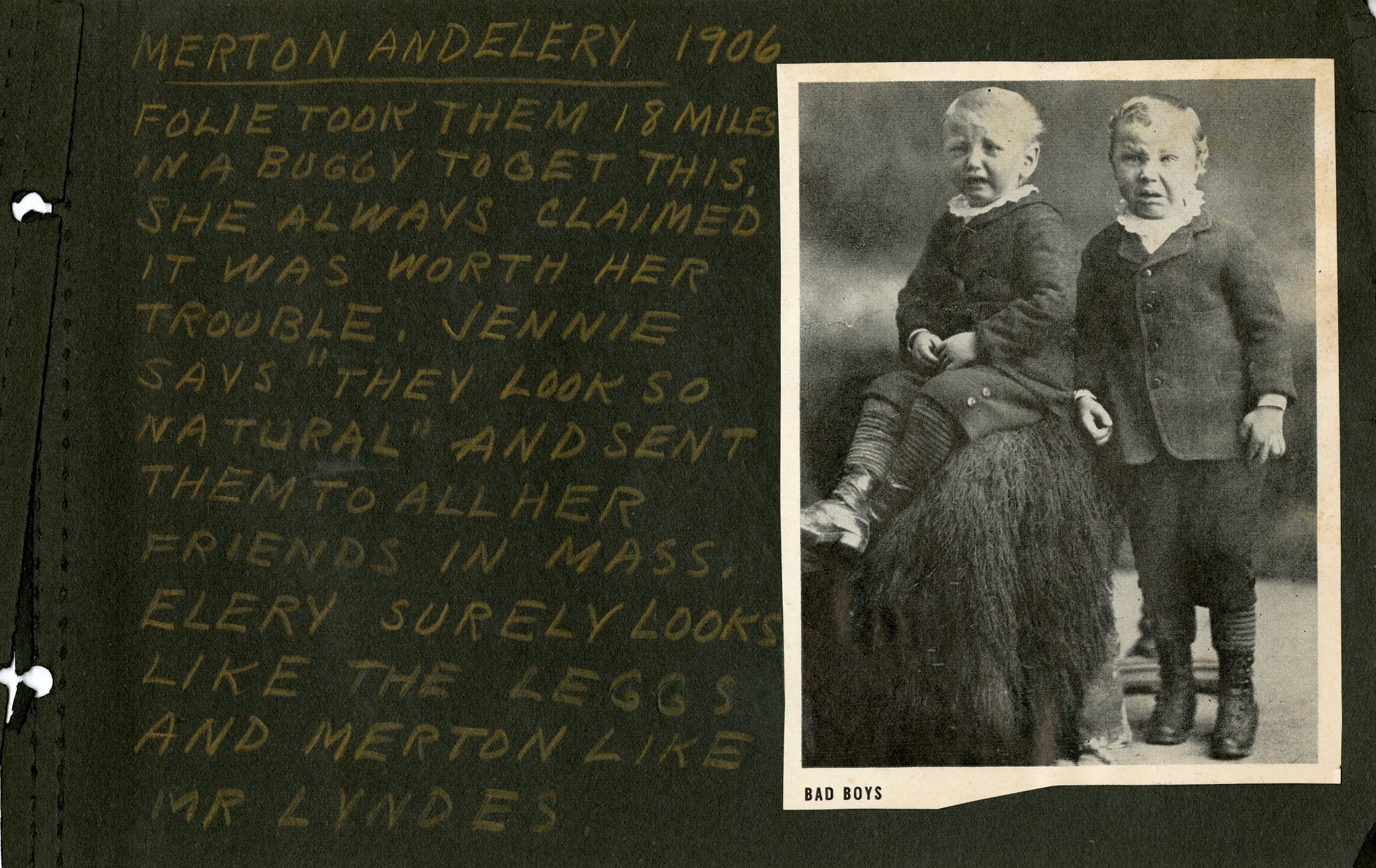

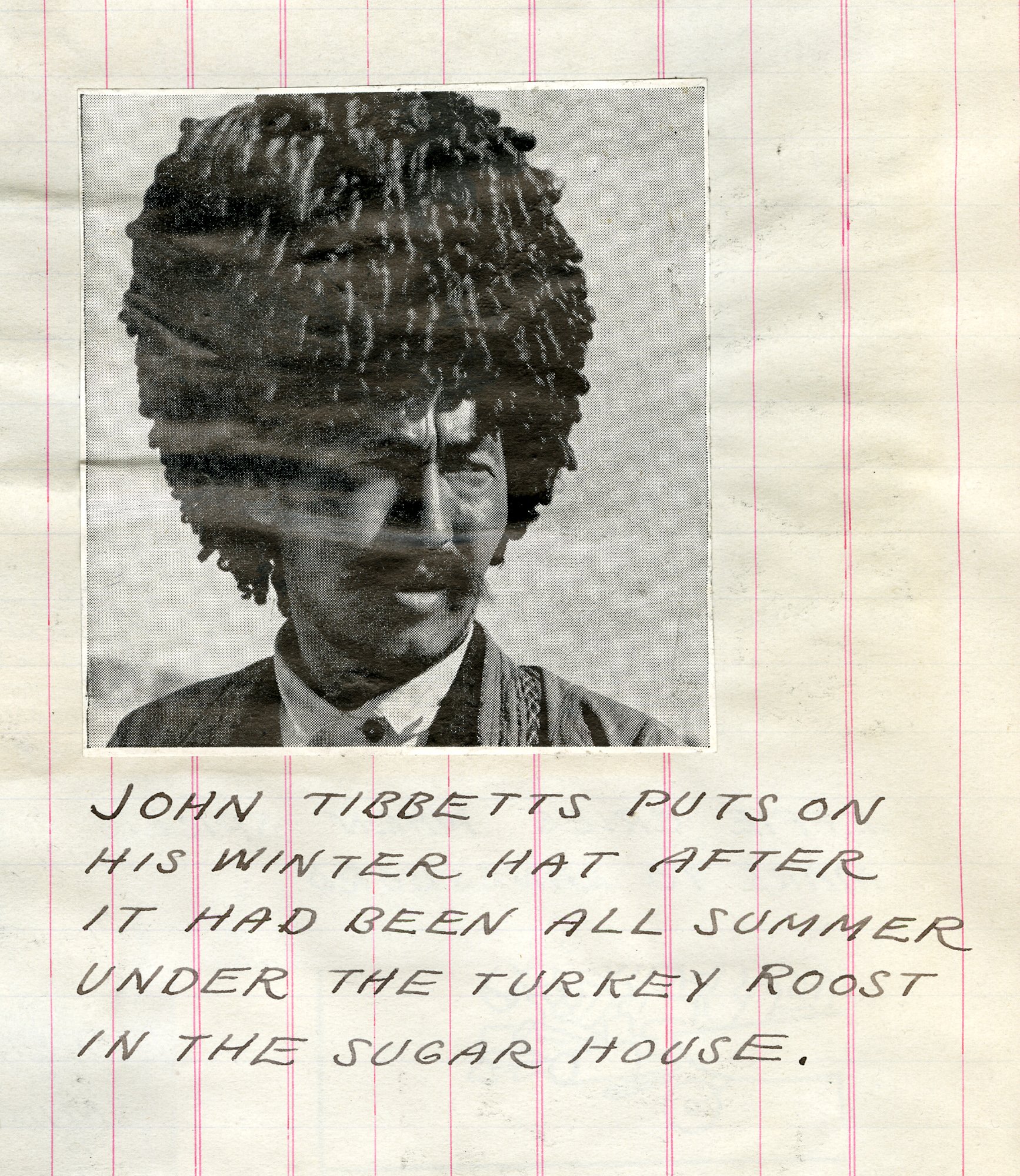

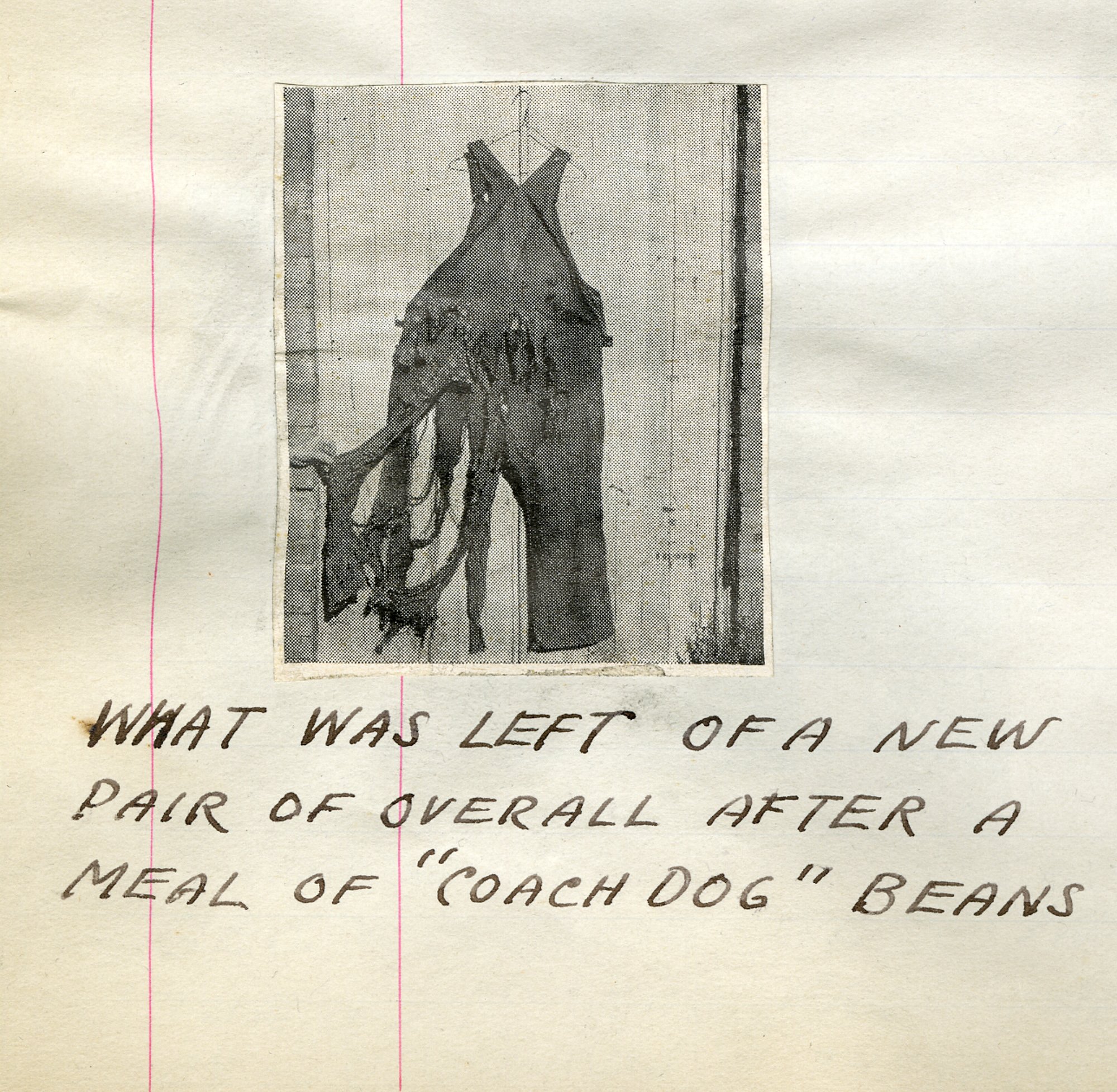

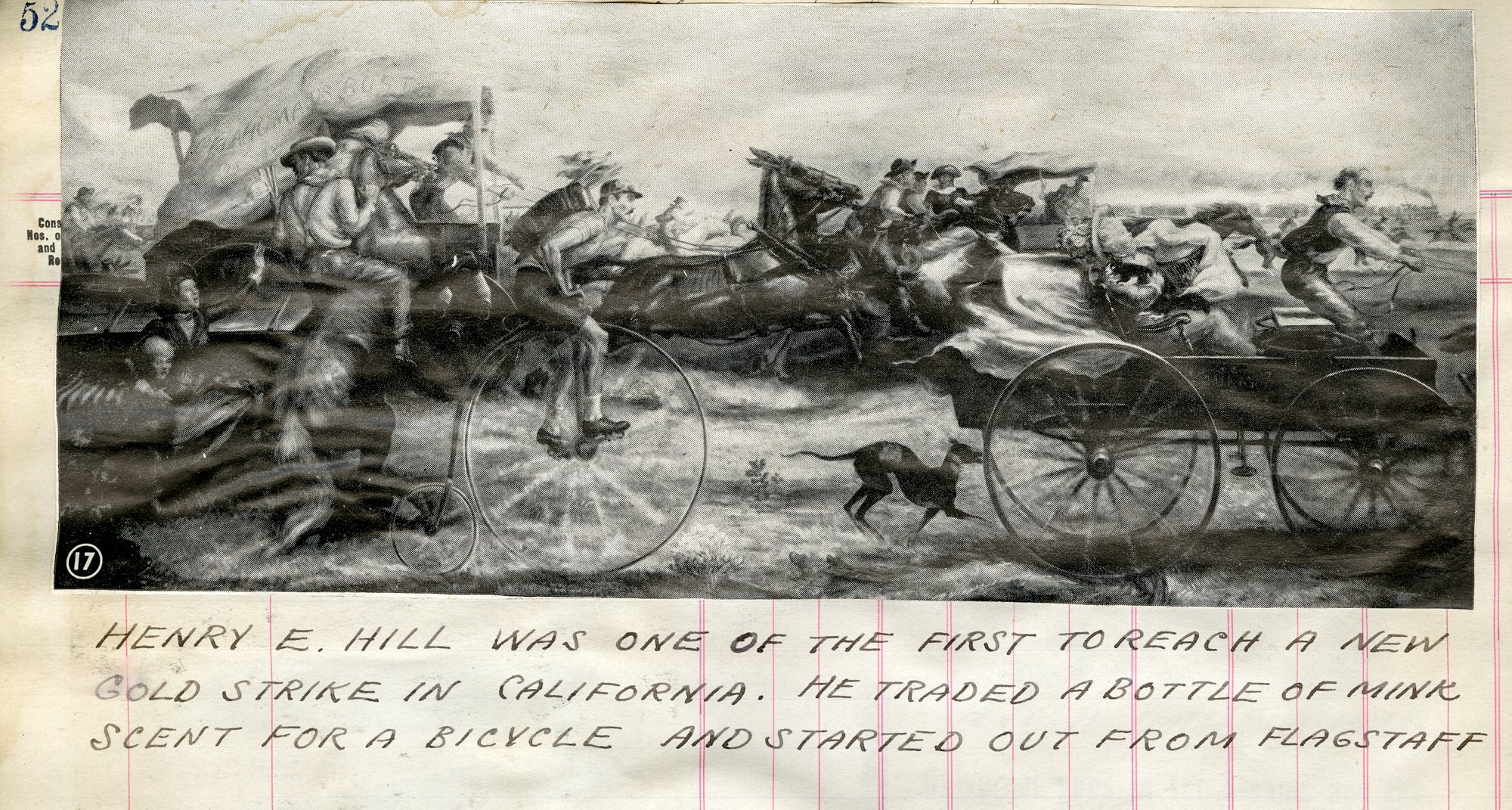

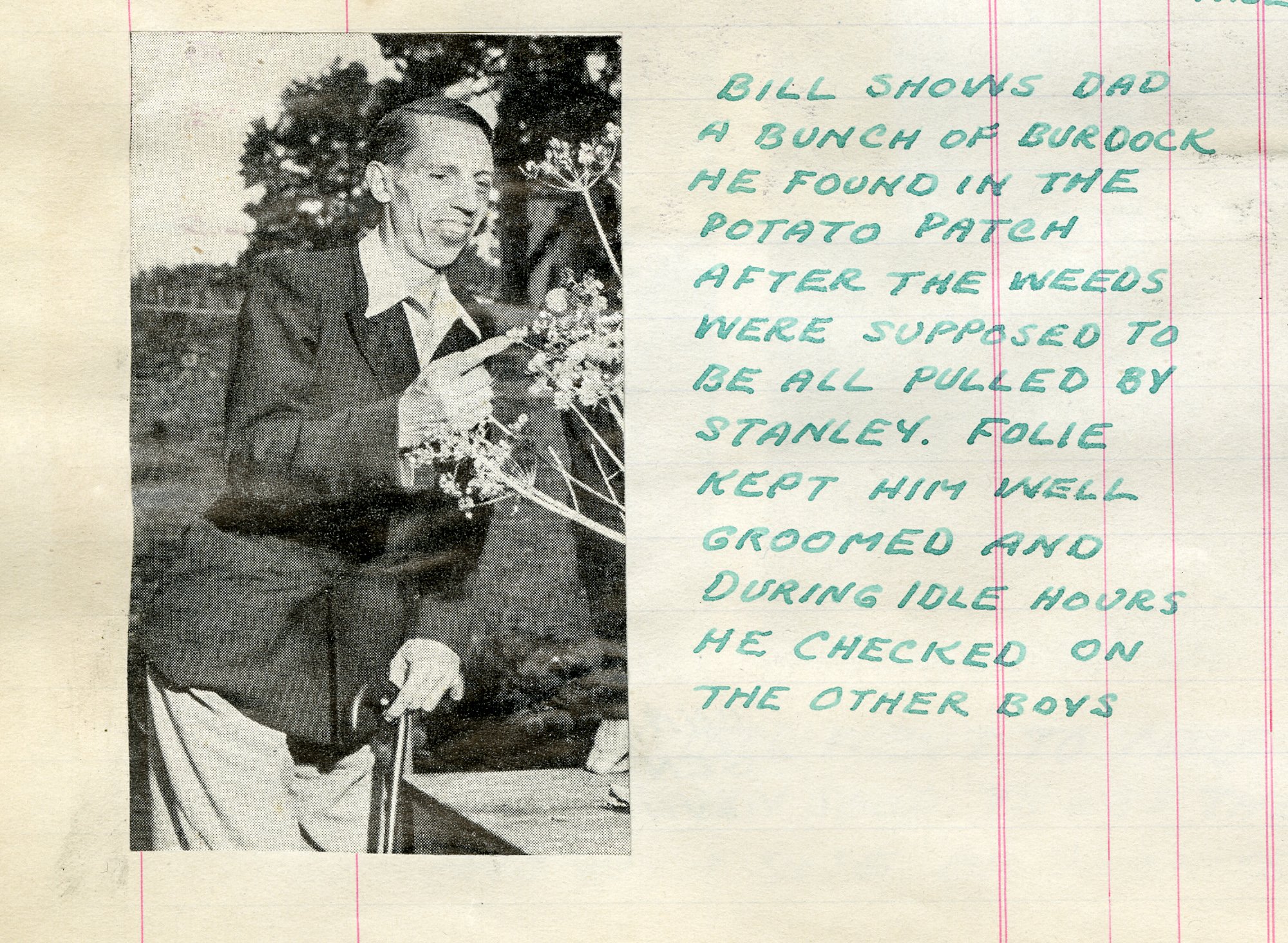

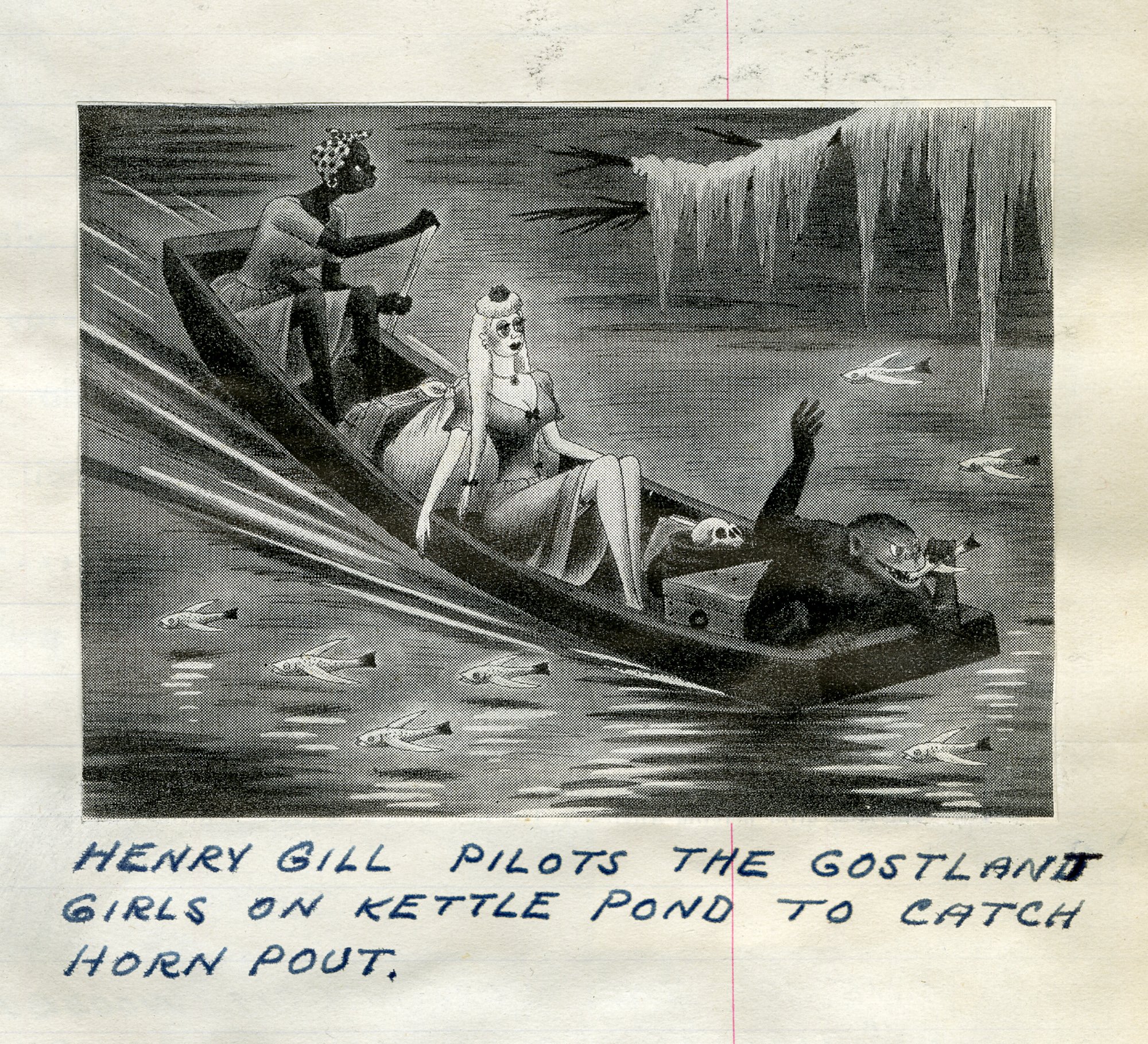

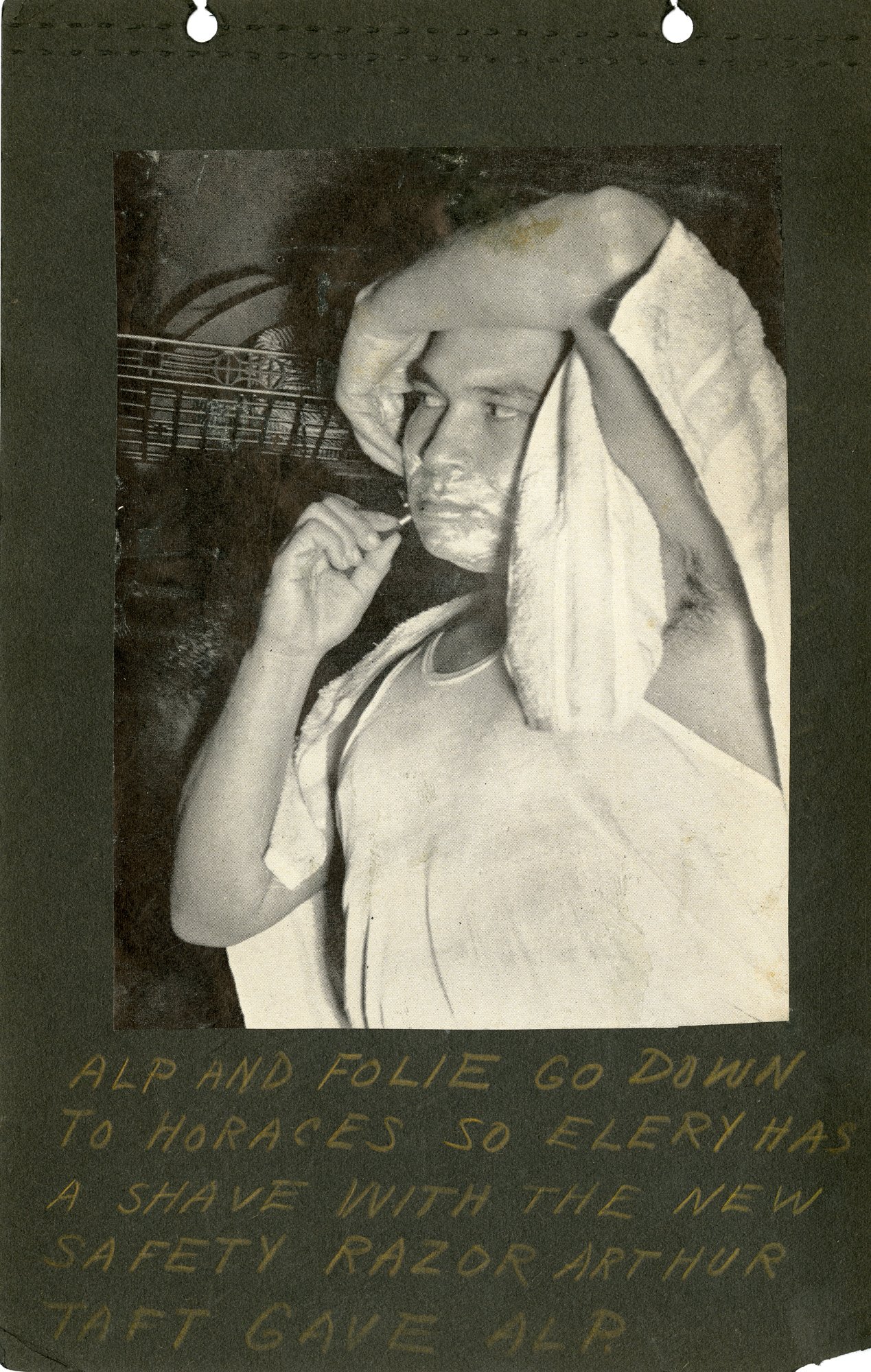

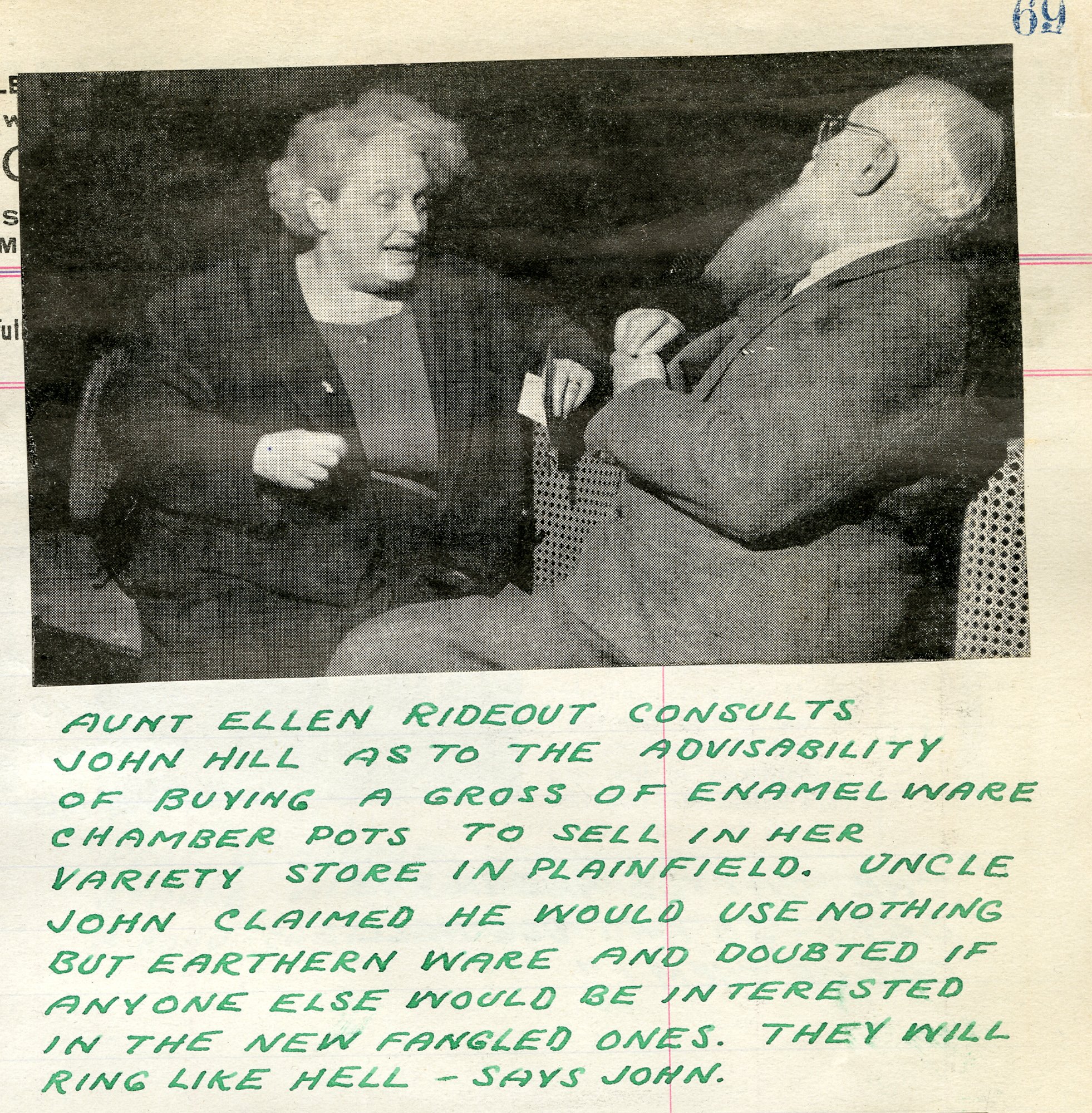

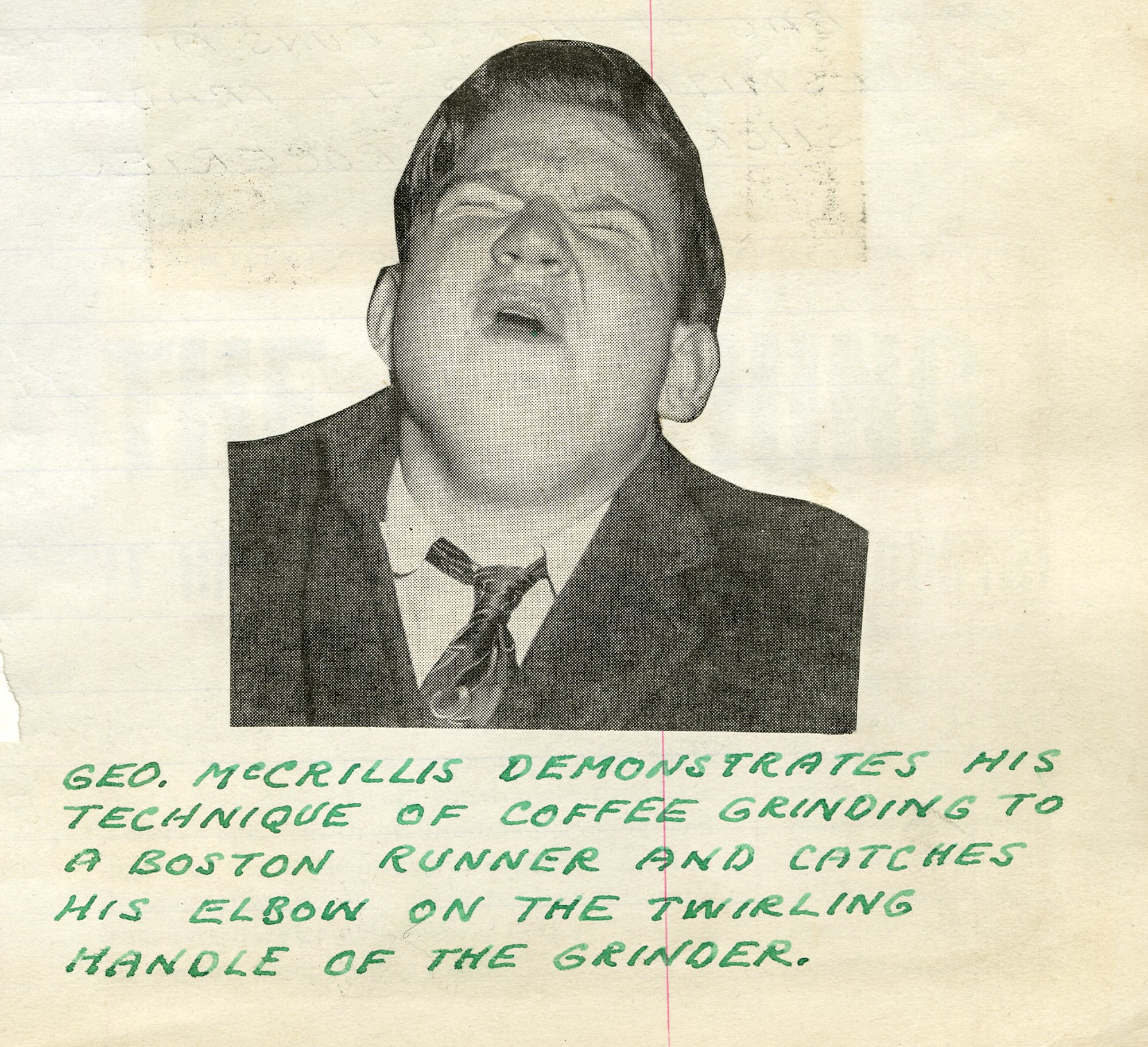

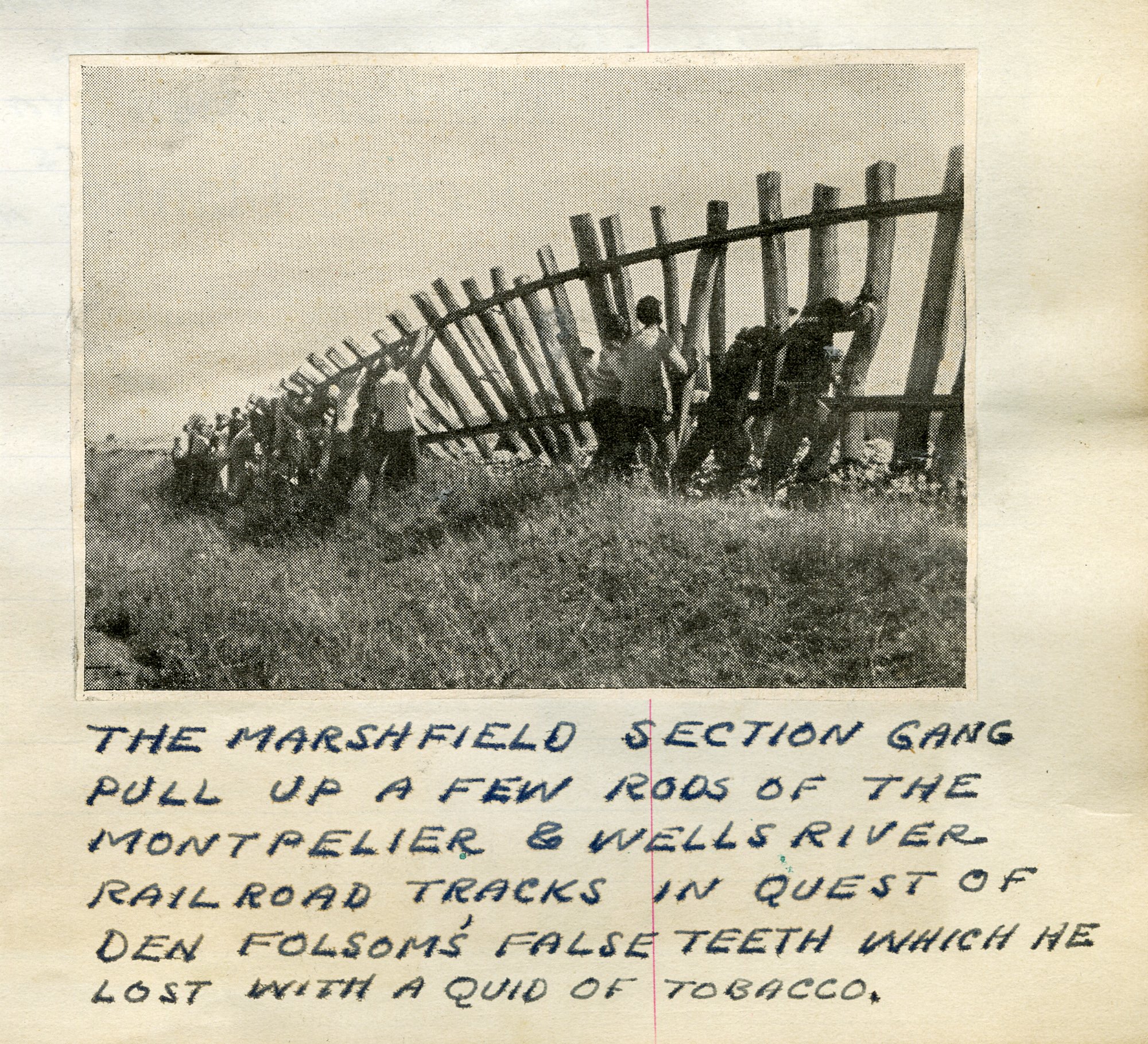

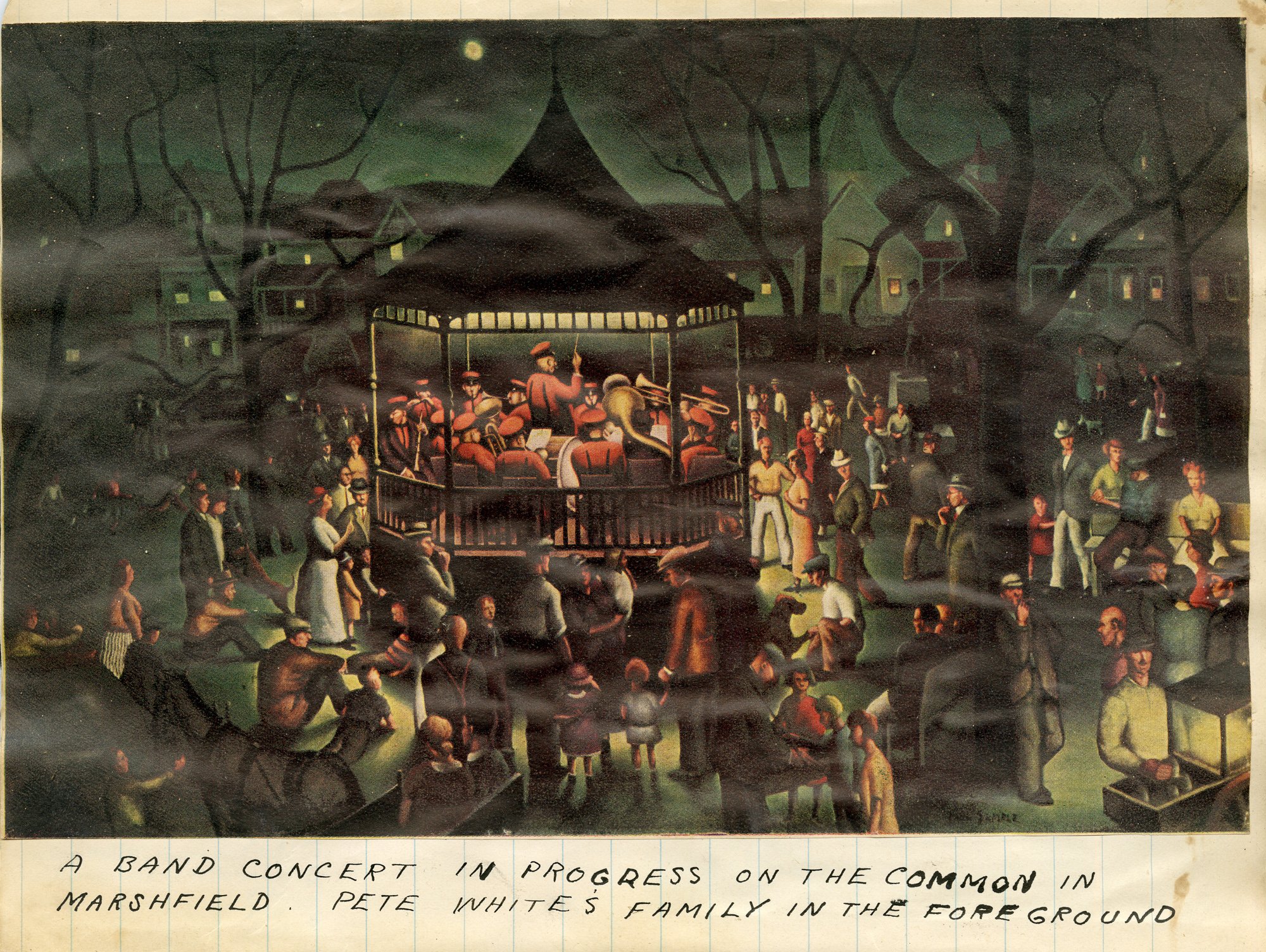

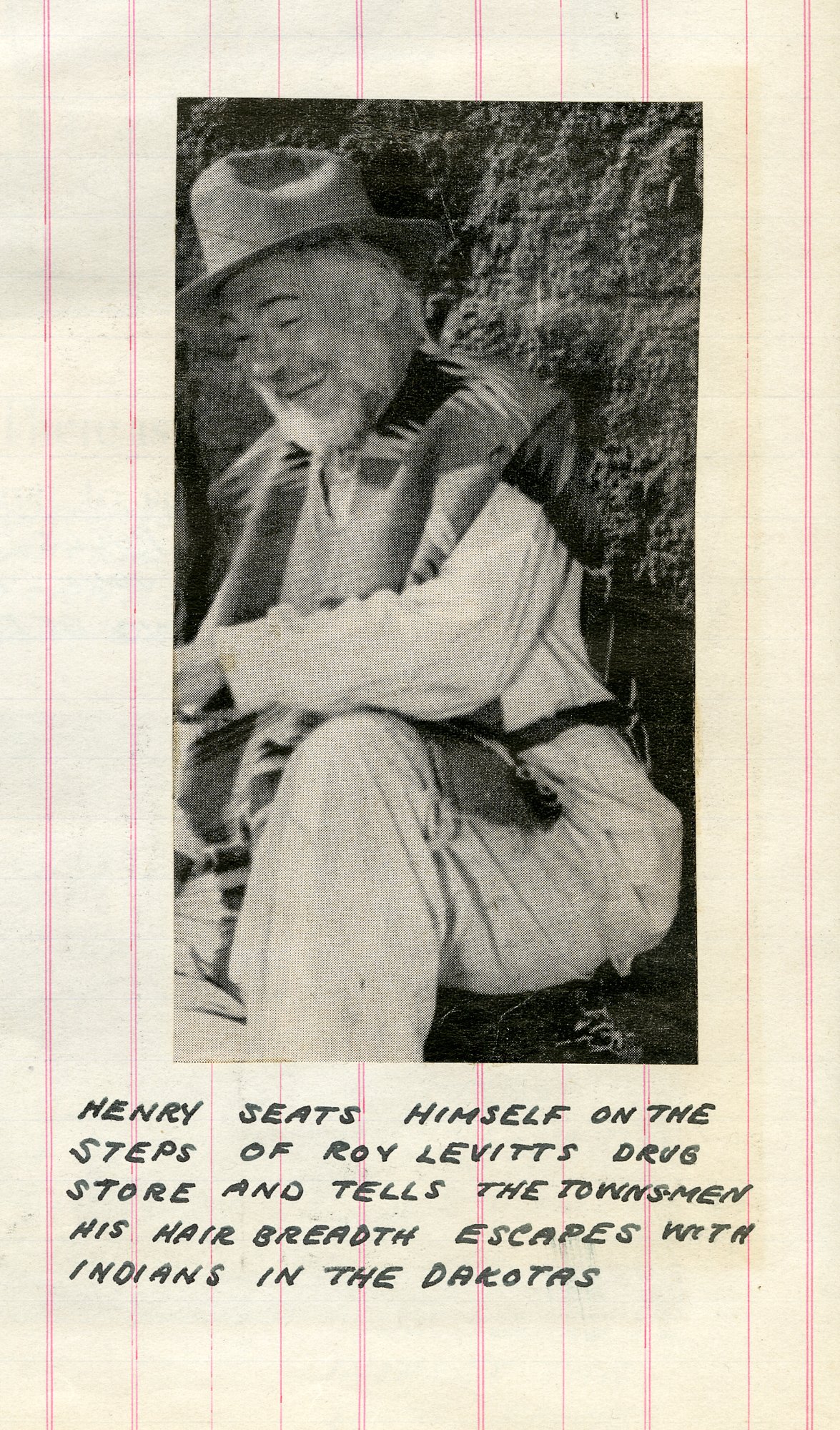

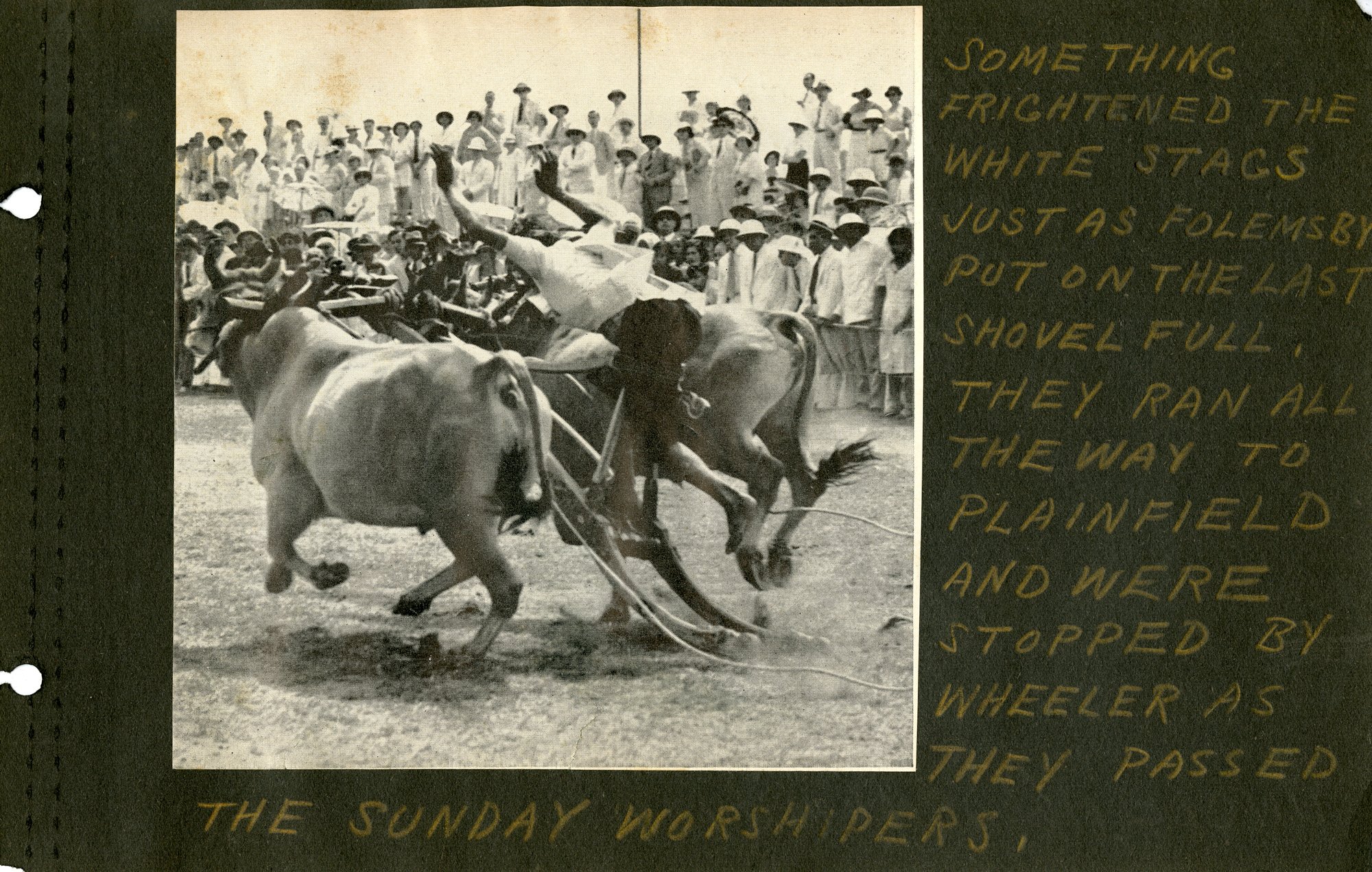

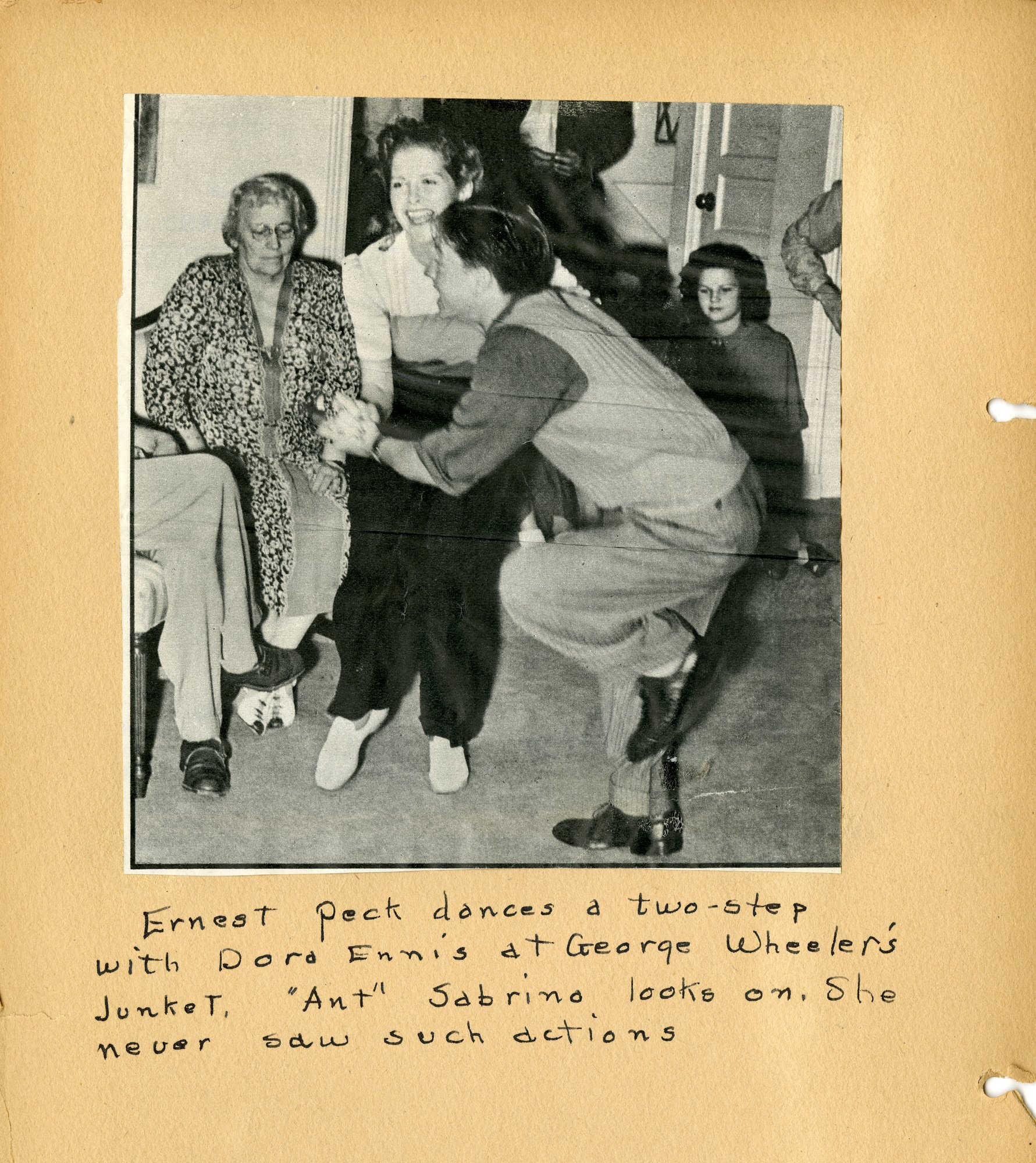

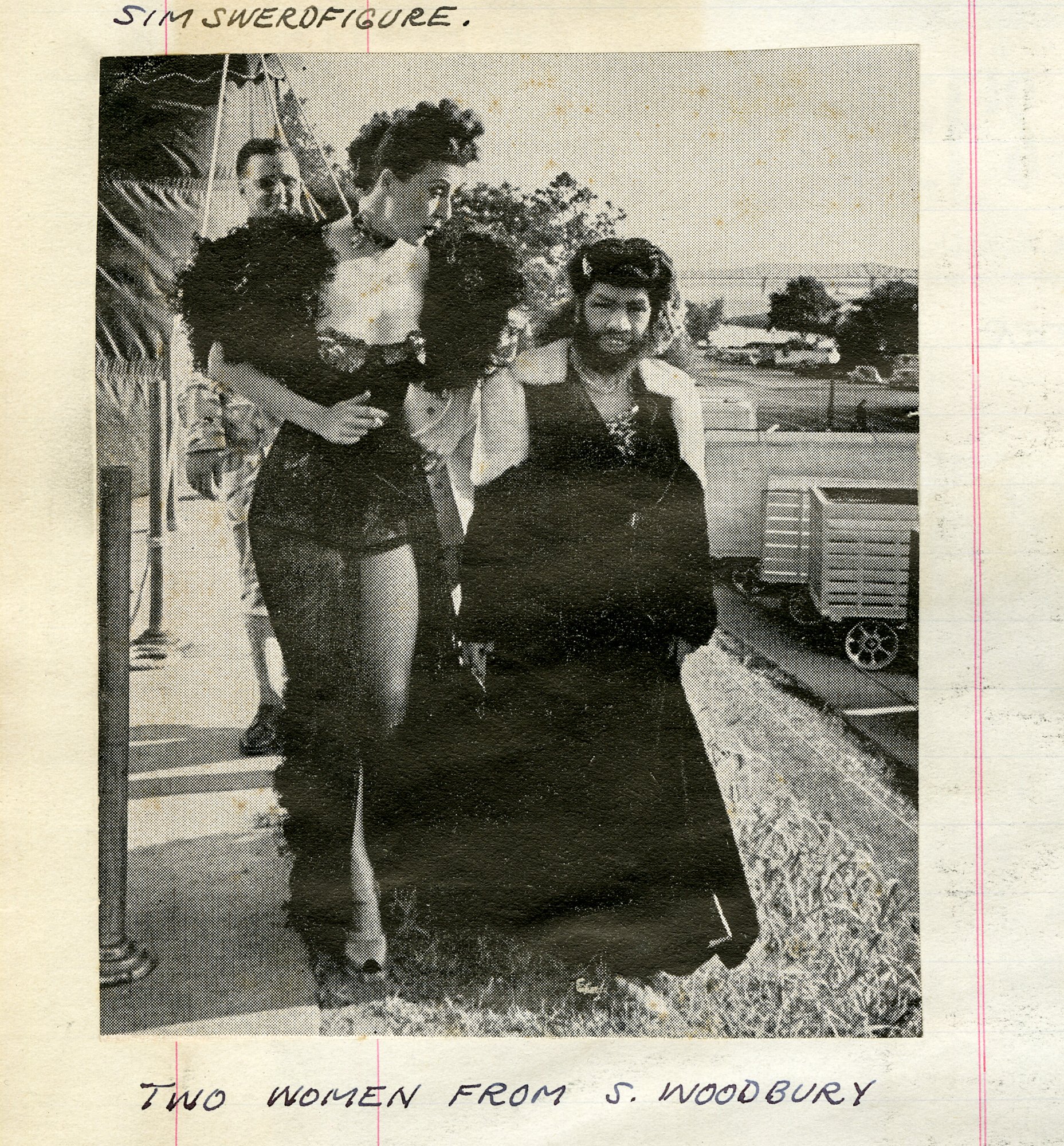

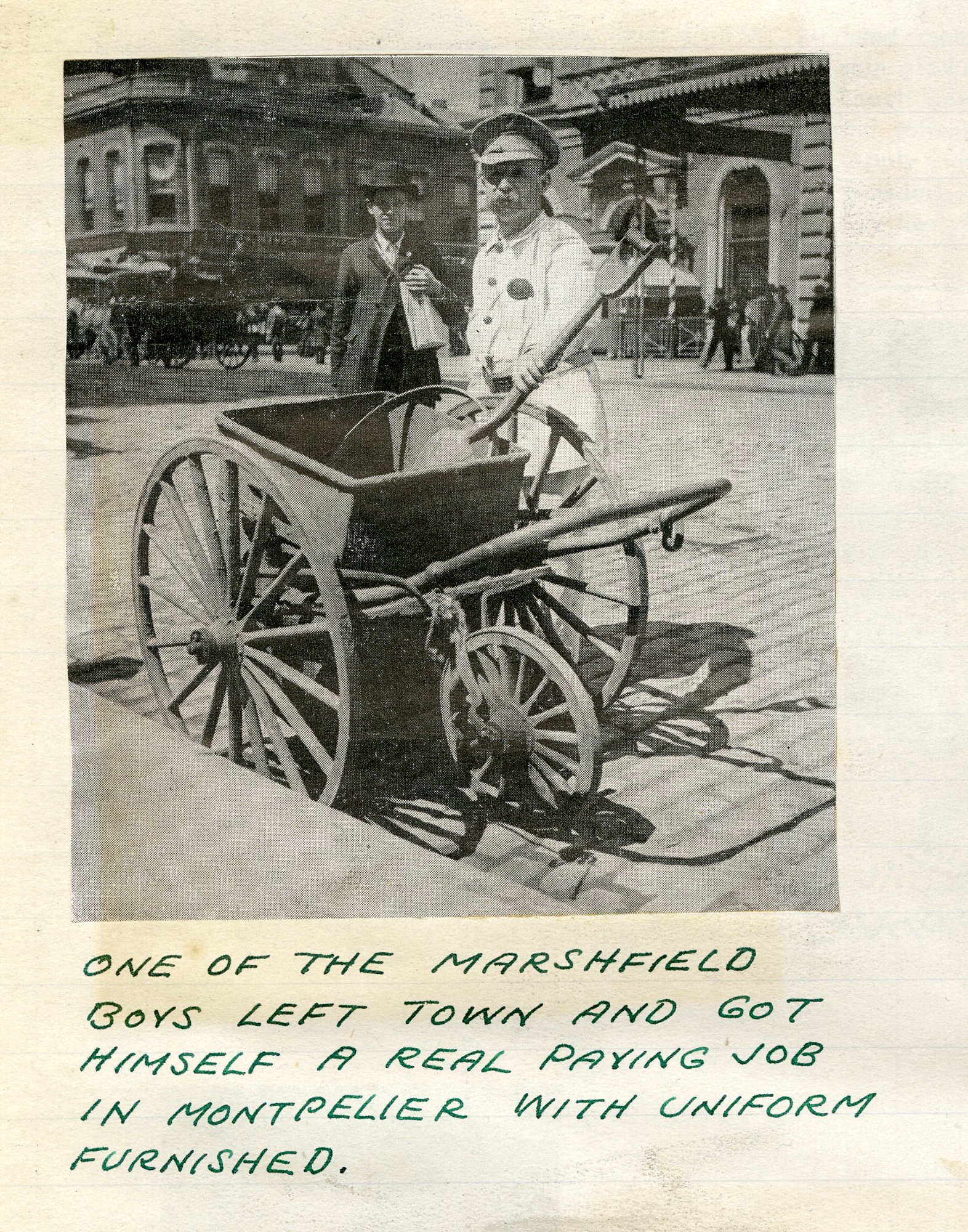

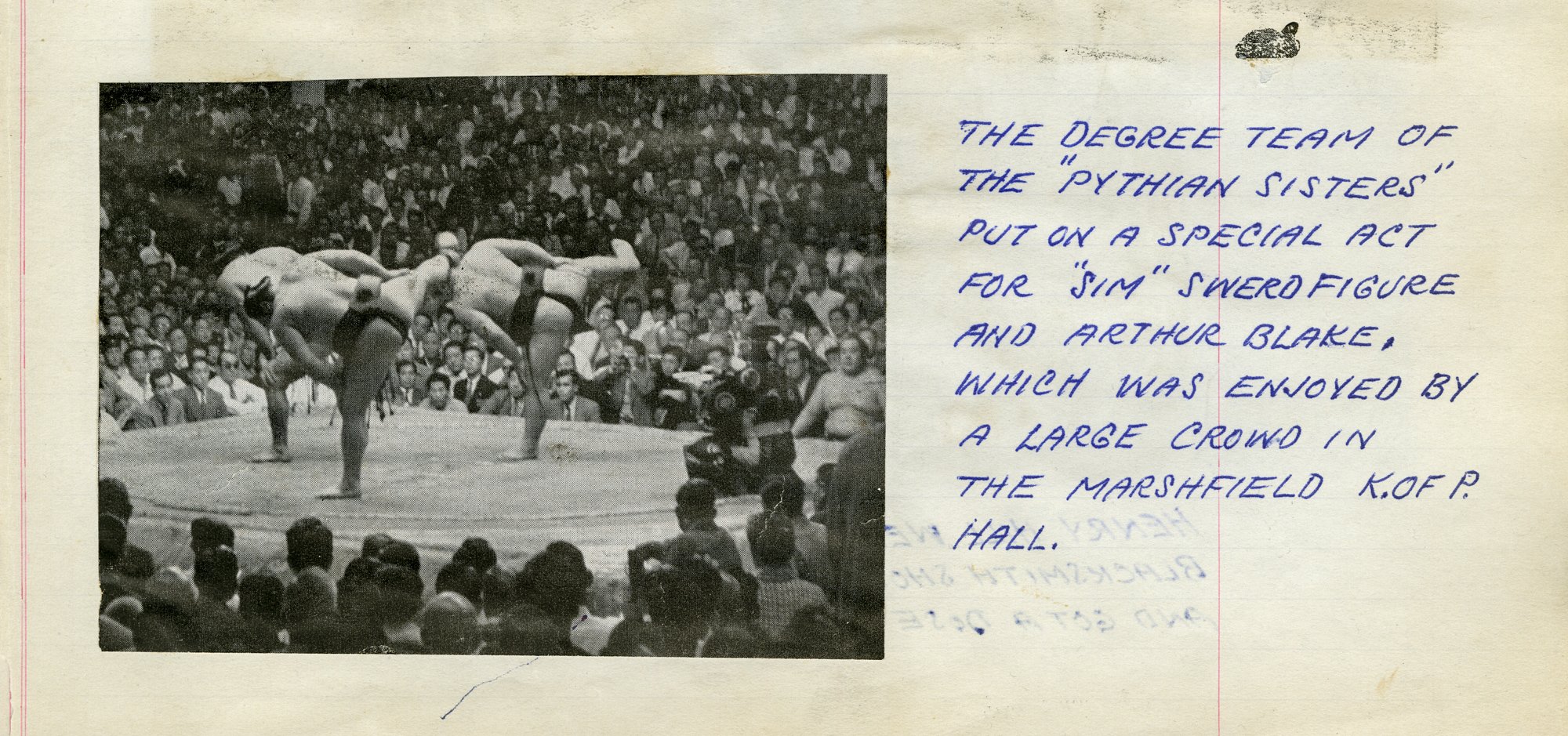

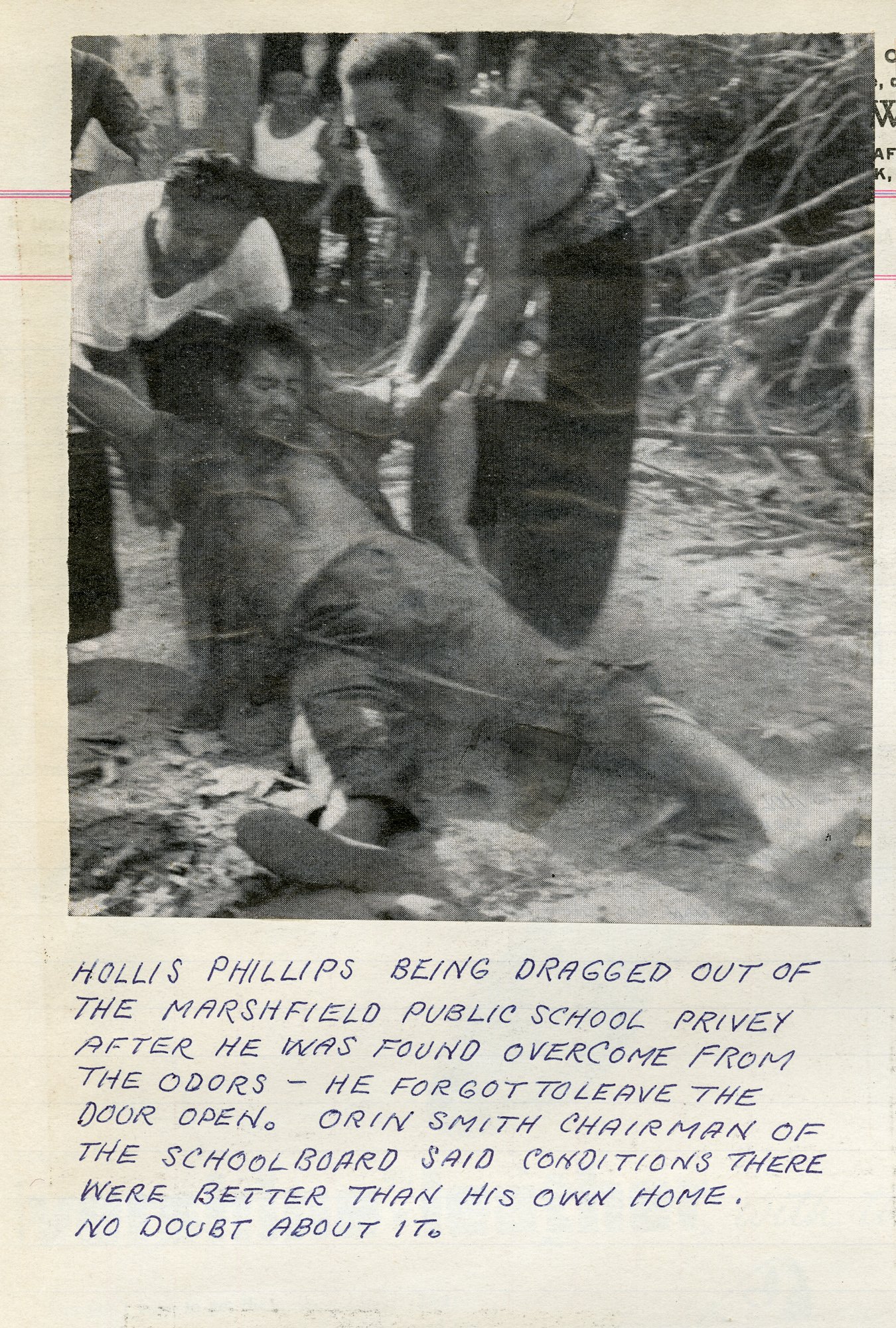

In 1933, Stanley became ill with a lung abscess and could not work. The family had to move home to his parent’s farm in Marshfield for the school year. Always in need of a project, he began cutting pictures out of National Geographic, Life and other popular magazines and publications—pasting them into various sized scrapbooks with captions that poked fun at family members, friends and neighbors.

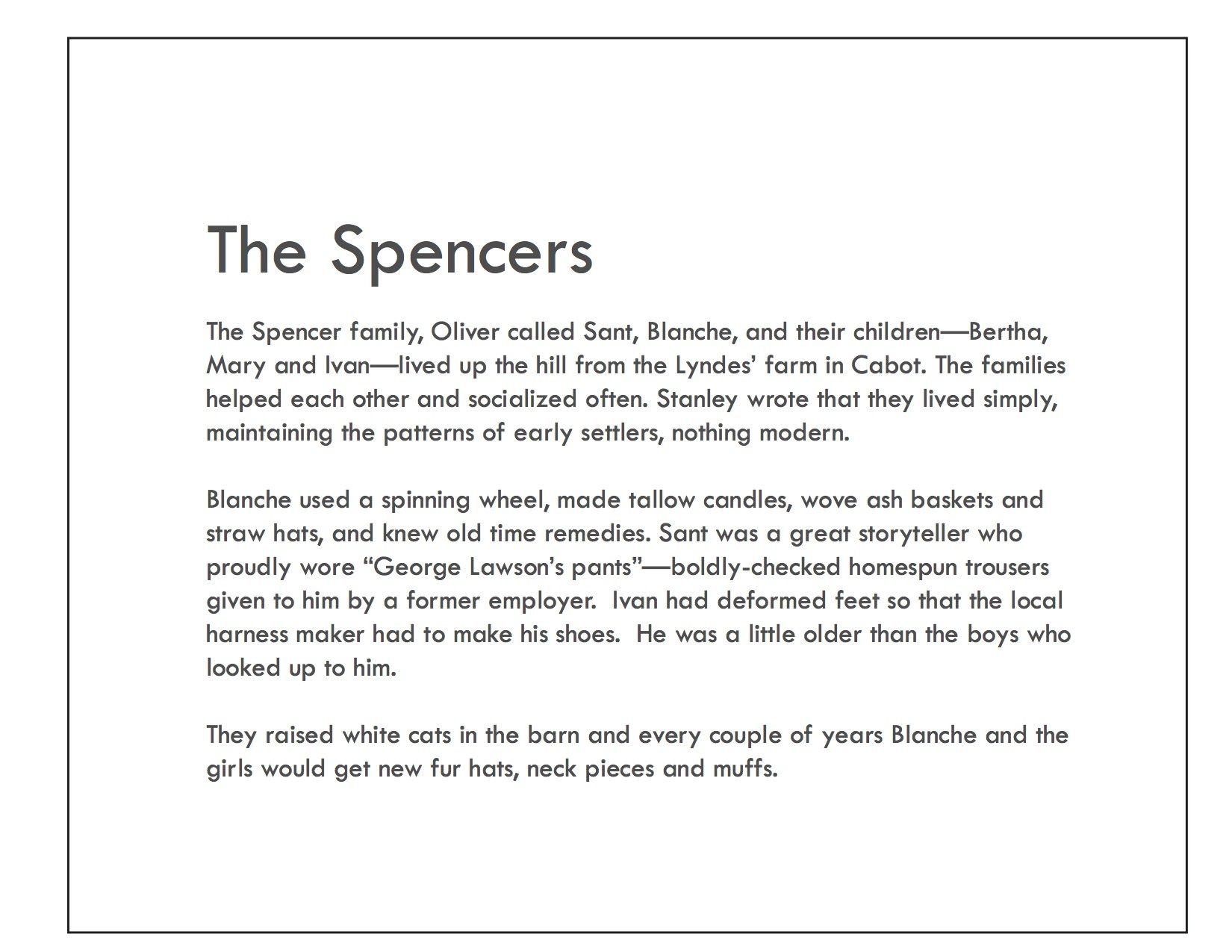

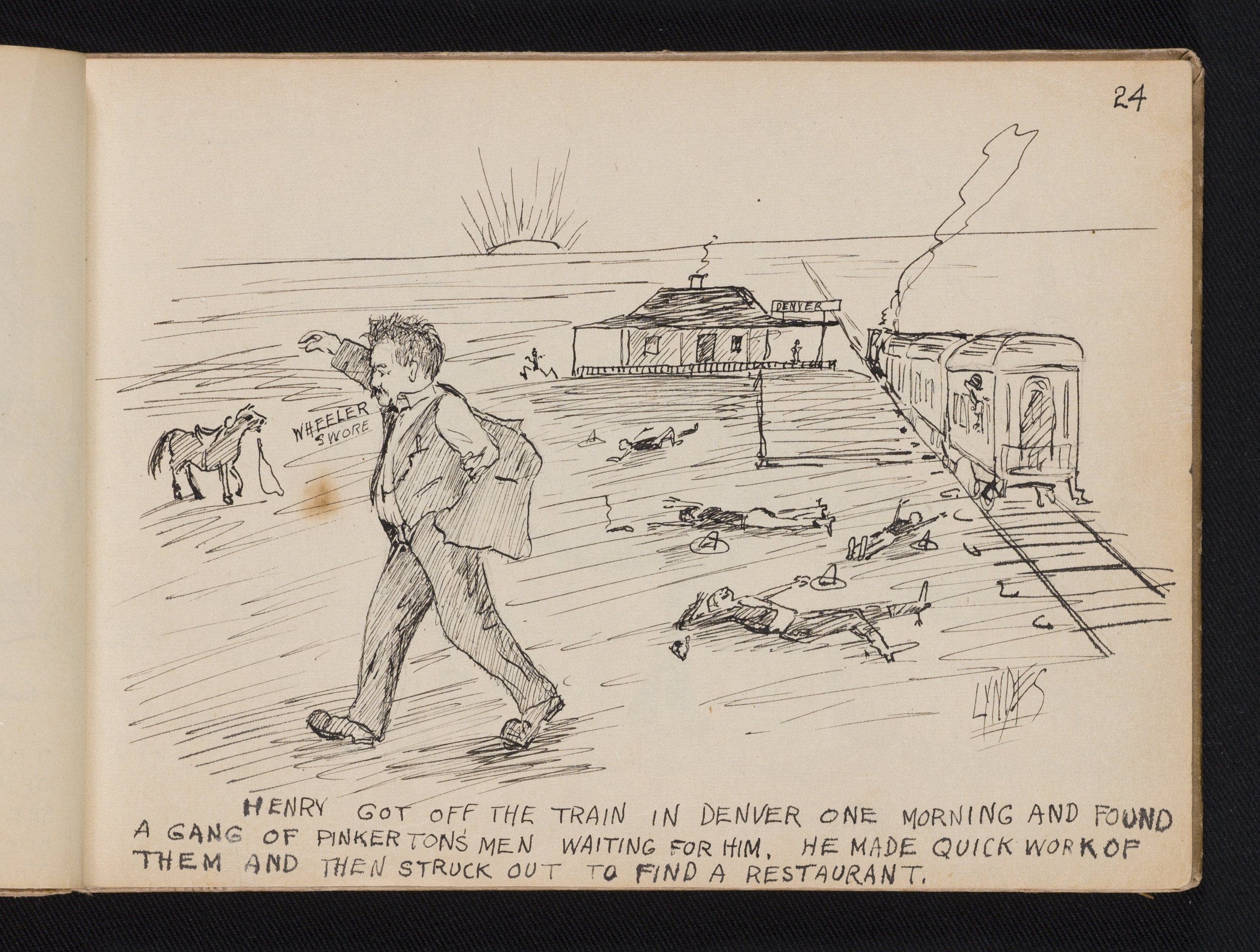

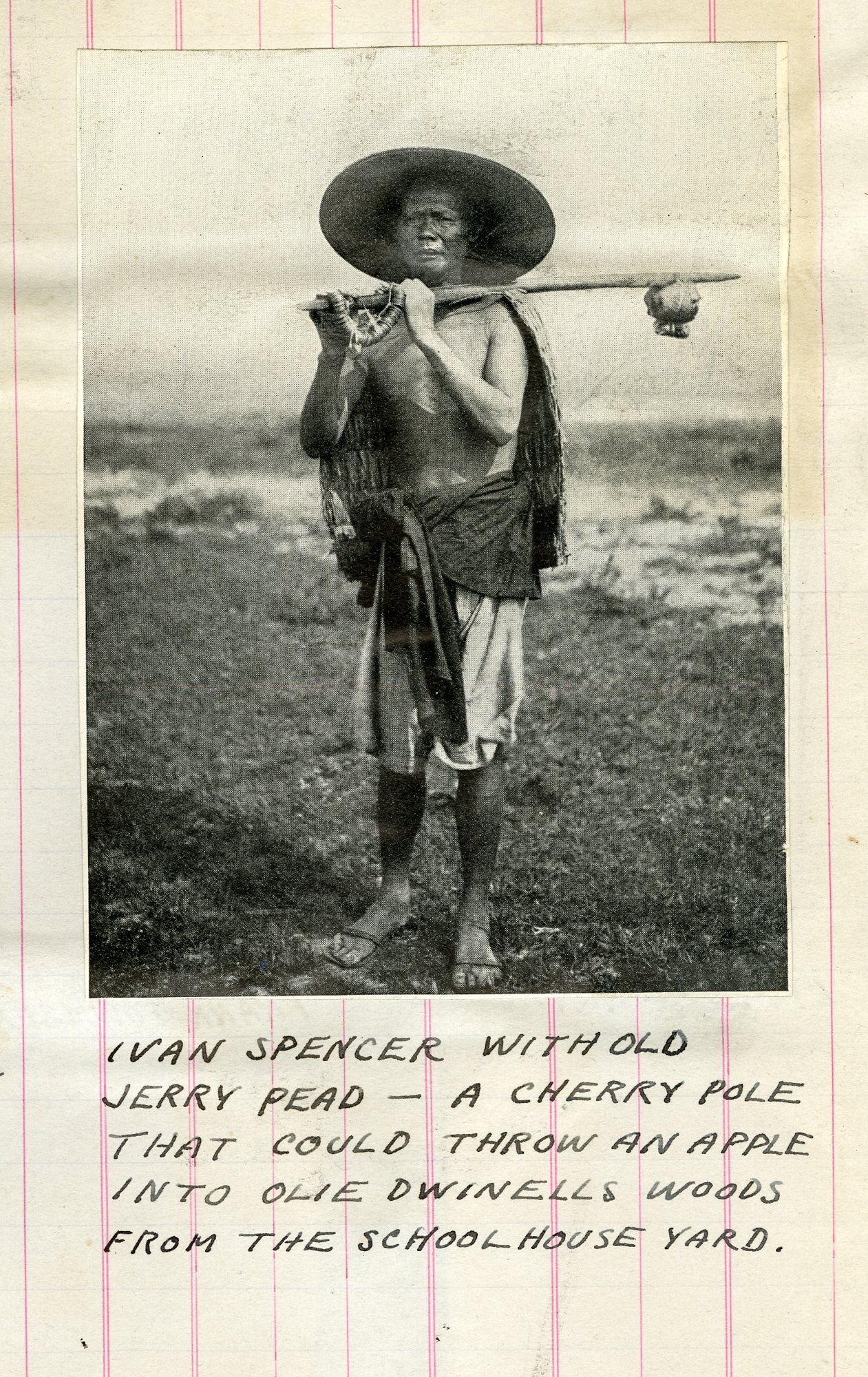

Much of the humor, and many of the stories that appear in the pages of the Family Traits book, echoed through these clippings, with their descriptive and often witty captions. Stanley’s youngest brother, Bill, can be found lounging lazily in the back of a wagon, Uncle Henry Hill is on lookout for Pinkerton’s Men, and the neighbor Ivan Spencer sports his favorite apple stick, Jerry Pead.

Family Quilt

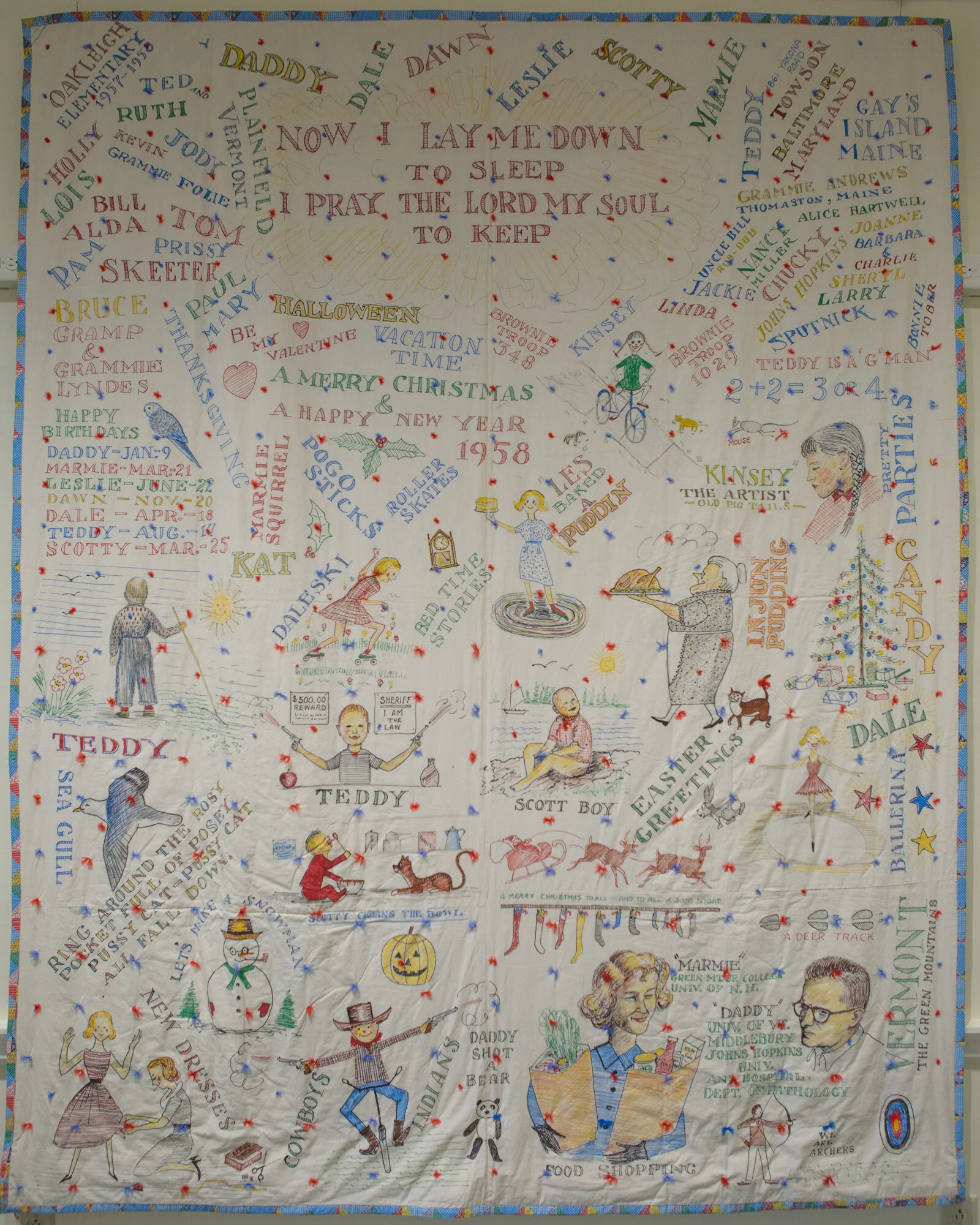

In 1958, Leslie and Dawn Andrews—the two oldest grandchildren—stayed with Gramp and Grammy Honeycake, while their parents were preparing to move. Gramp, as usual, had a project for them. He was excited by newly-discovered fabric paints and had them along with quilting materials at the ready. Inspired by the girls chatter, Gramp did most of the writing and drawing while the two girls colored in the shapes and figures. Grammy sewed the backing on the quilt and the girls helped her tie it. Colorful caricatures of family members fill the quilt, along with names for those not drawn to life by Gramp’s steady hand and fabric paint. Later, the quilt was entered into the competition at the Champlain Valley Fair. It won a blue ribbon—in a class by itself.

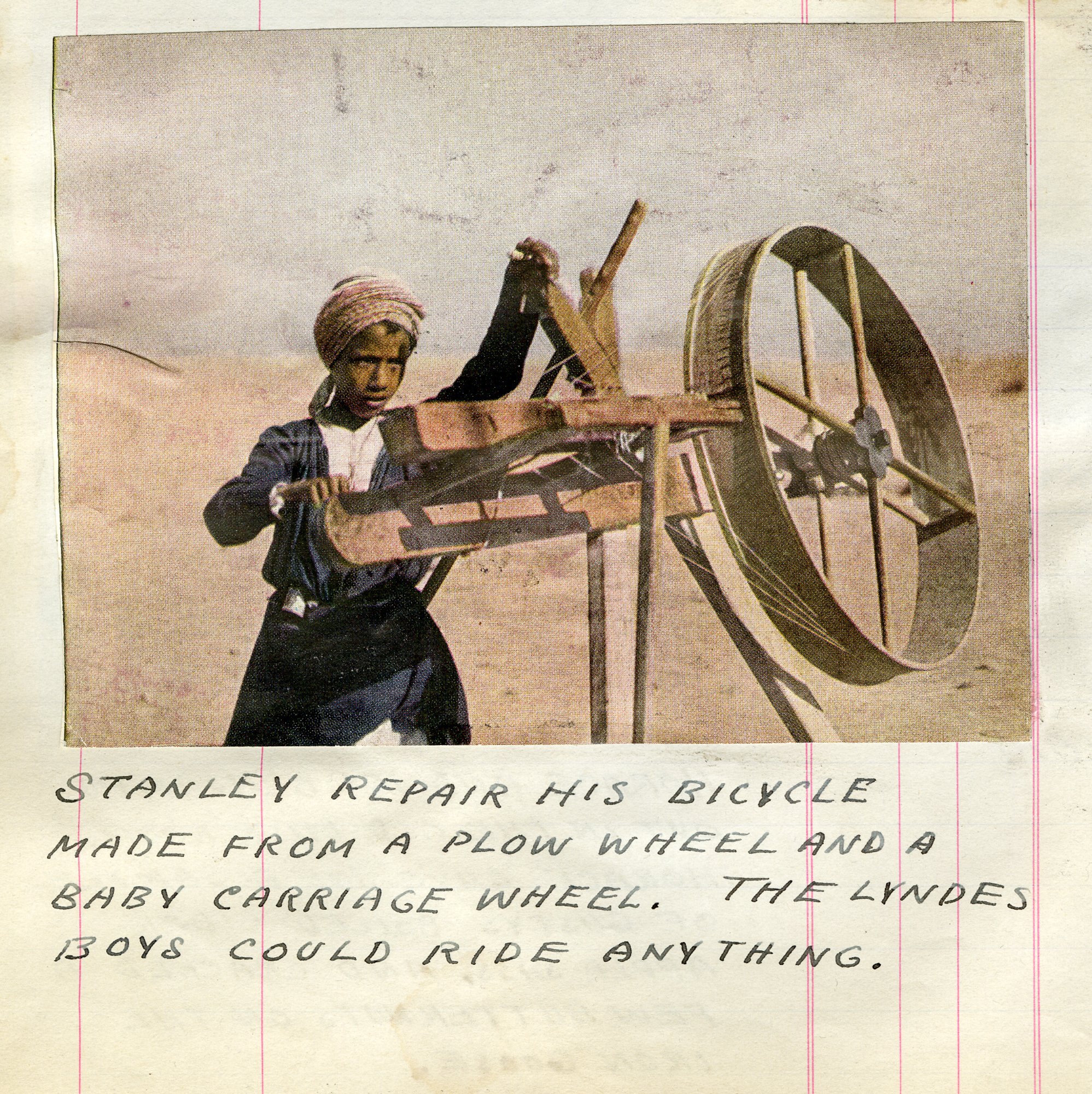

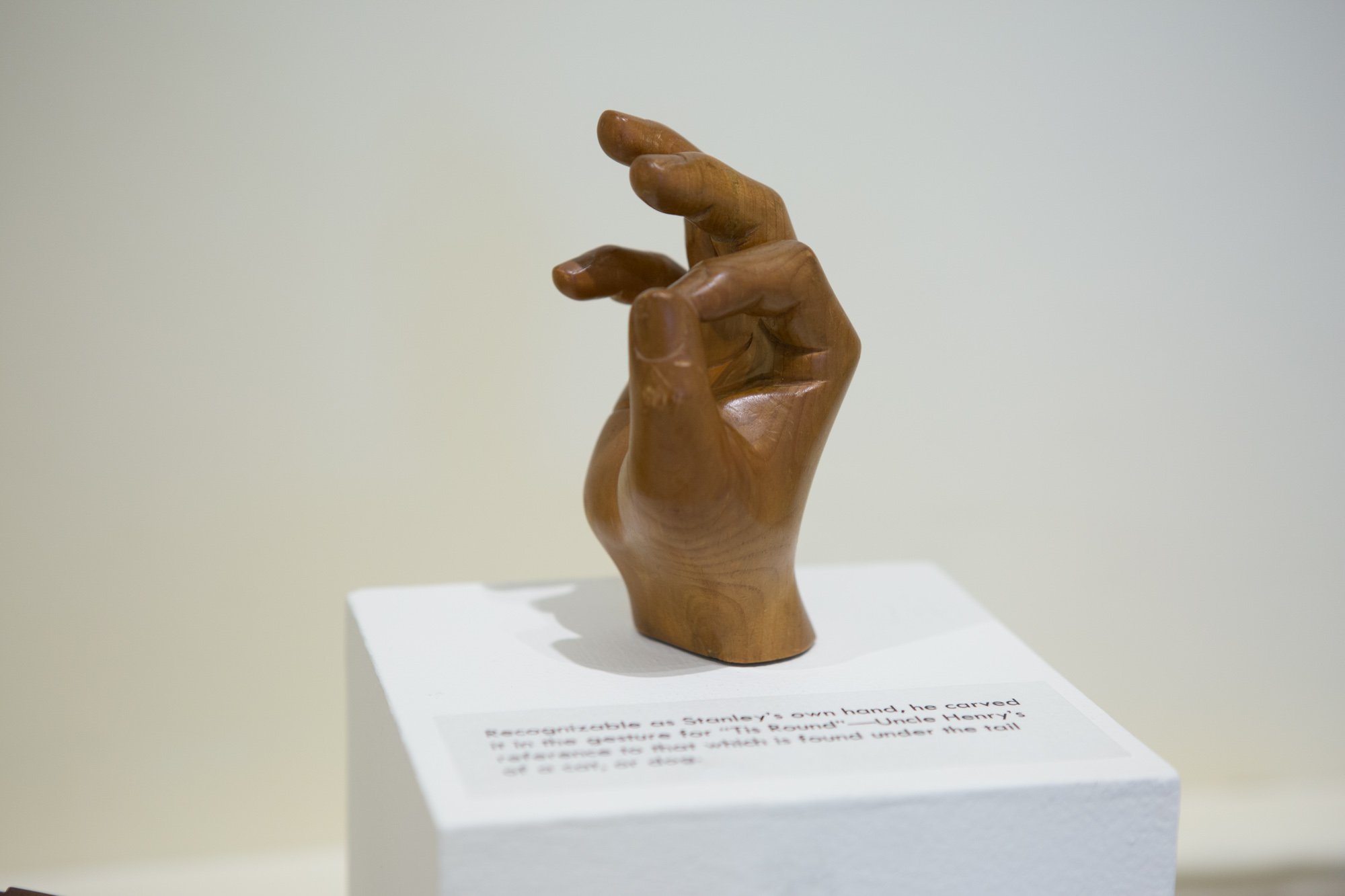

The Maker

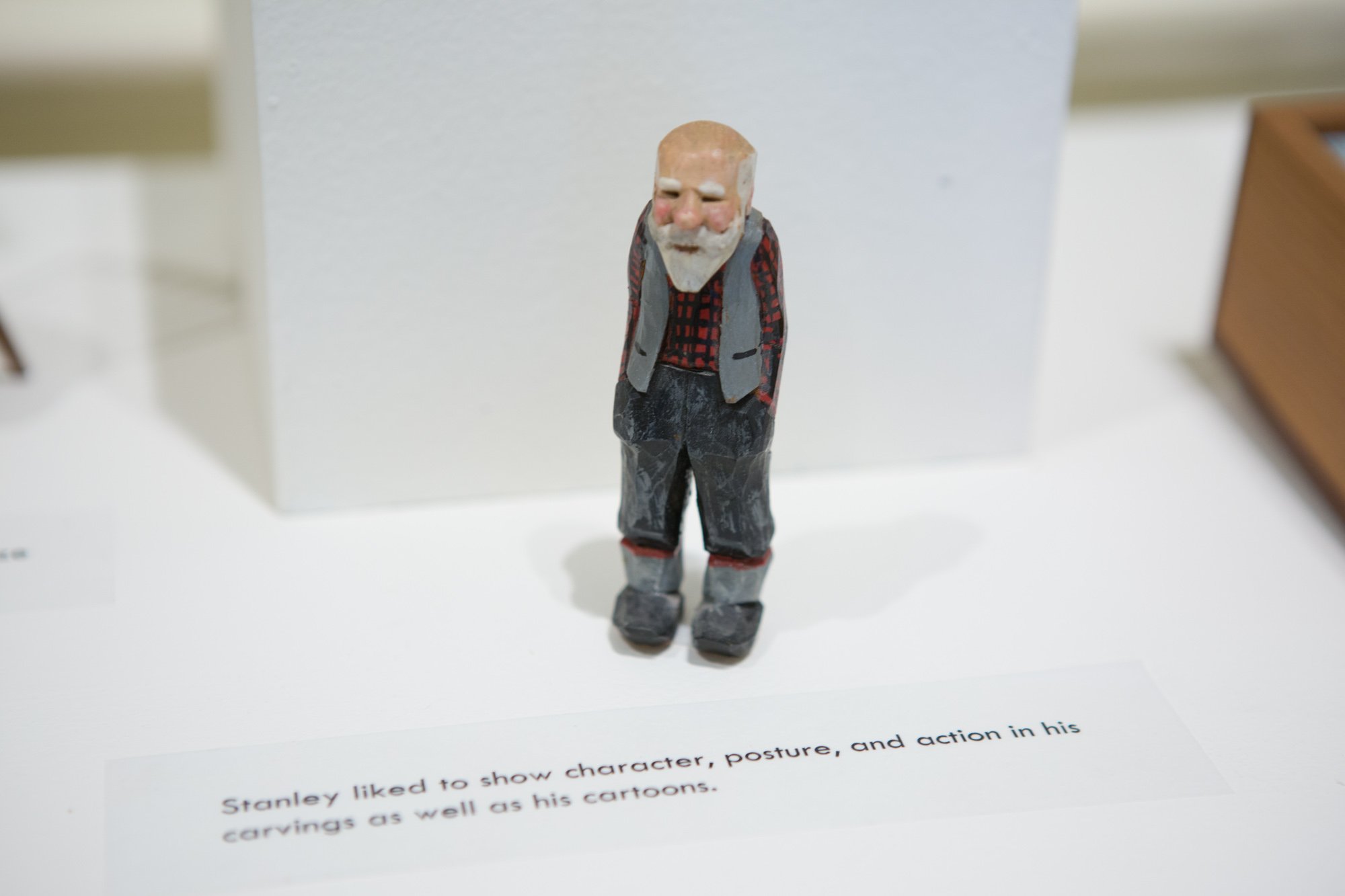

Stanley always made things. As a boy, he wanted a bike, but the family could not afford one so he made one out of some wood, a baby carriage wheel and a plow wheel. You could not pedal or steer it, but you could coast down a hill. He made himself bows, arrows, and darts for play and a cart for his brother Bill’s goat. After he left Pratt, most of his sketches and paintings were decorative or on birthday cards. As an adult, he did a lot of work in wood--furniture, bows, arrows, gun stocks, decorative objects, and carvings. He also made sure that his grandchildren had a steady supply of “boxes to put things in,” wooden guns, shields, swords, and other toys.

When his grandchildren visited, he usually had projects for them. Sometimes painting or assembling things made out of wood, gathering berries, or cooking.